In Tate Britain

Prints and Drawings Room

View by appointment- Artist

- Ivor Abrahams 1935–2015

- Part of

- Privacy Plots

- Medium

- Screenprint and flock fibre on paper

- Dimensions

- Image: 400 × 595 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by Evelyne Abrahams, the artist's wife 1986

- Reference

- P11105

Catalogue entry

Group of ninety-eight screenprints, lithographs and etchings, various sizes [P11099-P11196; incomplete]

Presented by Evelyne Abrahams, the artist's wife 1986

This group of prints was bequeathed to Evelyne Abrahams by the artist's parents, Harry and Rachel Abrahams, on the understanding that she would present it to the Tate Gallery on their behalf. It represents the greater part of the artist's printmaking to date. Other works by Abrahams in the collection are a sculpture entitled ‘Lady in a Niche’, 1973 (T03369), a work on paper entitled ‘Winter Sundial’, 1975 (T02330), and a small number of prints: ‘The Garden Suite’, 1970 (P04001-P04005), ‘Sundial I (Summer)’, 1975 (P07384) and ‘Untitled’ [from the artist's book Oxford Gardens: A Sketchbook], 1977 (P08150).

Abrahams is primarily a sculptor, and many of his prints relate to particular sculptures. In the period 1967–79 Abrahams focused on garden imagery, exploring the relationship between art, artifice and nature. Many of the images used in early prints were based on small, relatively poor quality photographs of gardens reproduced in gardening magazines, such as the weekly Amateur Gardening and Popular Gardening, or, less frequently, better quality illustrations found in the series of volumes on gardens published by Country Life in the 1920s. This use of second-hand source material gives much of his printed output a conceptual quality, and links his work to Pop art. Abrahams has presented a large amount of source material relating to his printmaking of this period, including magazine clippings, photographs and sketches and acetate stencils, to the Tate Gallery Archive (TGA 8315).

The critical and commercial success of ‘The Garden Suite’ (P04001-P040054), published in 1970, helped establish Abrahams' name internationally, and in the following decade he went on to produce a significant body of prints, making approximately one print a month. The dealer Bernard Jacobson published many of his portfolios, and the Mayor Gallery organised a series of touring shows of prints and sculptures. In this period Abrahams was based in London, working at a studio in Leonard Street, EC2, from 1969 to 1982, and at the A & A Foundry in Bow from 1982 to 1992, with a second studio at Butler's Wharf from 1974 to 1979.

In 1979 Abrahams abandoned the garden theme for which he had become well known and focused instead on water-based imagery, using bathers and nymphs which were inspired in part by the landscape, myths and folk customs associated with the South of France. Abrahams and his French wife bought a home in Pézenas, in the Languedoc, in 1973, where he used the cellar as a studio. In 1988 they bought a house in the small village, Castelnau de Guers, in the same region, and have lived there on a full-time basis since 1992.

Unless otherwise stated, all quotations by the artist in the following entries are taken from a taped interview with the compiler held on 18 August 1994. The entries have been approved by the artist.

[from] Privacy Plots 1970 [P11101-P11105]

Suite of five screenprints with flock fibre on Crisbrook wove paper, various sizes; printed by Christopher Betambeau at Advanced Graphics and published by Bernard Jacobson Ltd in an edition of 75 plus 10 sets of artist's proofs of which this is one

Repr: Ivor Abrahams: Environments, Skulpturen, Zeichnungen, Komplette Graphiken, exh. cat., Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne 1973, pp.84–5

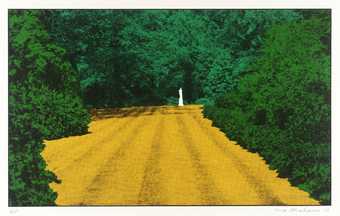

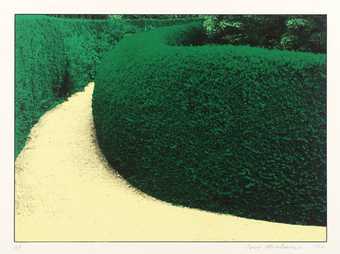

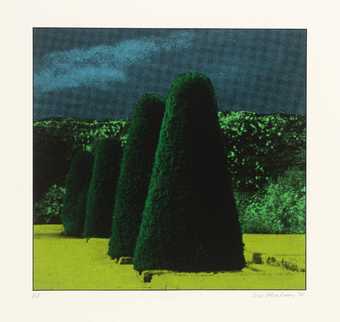

According to the artist, ‘Privacy Plots’ was made six or seven months after a set of screenprints entitled ‘Garden Suite’ (P04001-P04005). The earlier suite, which was printed at Kelpra Studio and published in February 1970, featured elements which were to become recurring motifs in Abrahams' work of the 1970s: topiary, garden fences, hedges and curving paths. The suite had been well received, and ‘Privacy Plots’ was intended to quickly follow up this success.

Abrahams began to flock his sculptures in 1970 (see, for example, ‘Small Rockery’, 1970, repr. Cologne exh. cat., 1973, p.31 in col.), and wanted to incorporate this textural effect in his prints. In conversation with the compiler he explained that this was not something he could have attempted with the master printer Chris Prater at Kelpra Studio:

I moved over to Betambeau because a lot of the people who worked for Chris Prater opened up their own shop with the help of Eduardo Paolozzi who set them up. They were obviously a lot more experimental. Prater would never have undertaken a job like this because it was a completely new technique that had never been applied to screenprinting before. Advanced Graphics were very keen to do this, and we pitched in and did it.

In ‘Autobiography’ (Ivor Abrahams, exh. cat., Bernard Jacobson 1994, p.96), Abrahams described Betambeau as a ‘wonderful screen printer, completely open, for whom nothing is too much trouble. The best person I have known with mixing and matching colours’.

A description of the electrostatic flocking process is given in the Cologne catalogue (p.80):

Adhesive is applied over the surface to be flocked. Flock fibres are fed into a gridded hopper and are pushed towards the wire grid by means of a revolving paddle which is turned by compressed air. The fibres are then subjected to an electrostatic charge causing them to shoot out through the grid in thousands of individual particles.

The single fibres embed themselves in the adhesive standing up on end, creating a fibrous, piled surface like a carpet.

The fibres are precision cut in Switzerland and are between a quarter and three millimetres in length. Three grids are available for the electrostatic flocker: fine, medium and coarse. By varying the grid size with the flock millimetre ( 1/4, 1/2, 1, 2, and 3) considerable textural variety is created.

To add areas of flocking to the ‘Privacy Plot’ prints, a stencil was designed to print adhesive rather than ink, and the flock was applied from a gun. Abrahams himself bought the ready-dyed fibres from a supplier in Switzerland.

Each of the screenprints is based on a photographic image. The artist cannot remember the particular sources he used but in conversation with the compiler said that the images were probably taken from gardening magazines. The images were rephotographed by a professional photographer employed by the printer, enlarged and then worked upon by the artist in collaboration with Chris Betambeau before being used to make a photostencil. In most cases, the source image was a poor quality, monochrome image with little detail. In conversation the artist stressed that, in the making of the stencils, very little of the original image remained: the photographs provided the idea for the composition and the basic outline shapes. The contrast between the photographic and hand-drawn elements in the prints helps create a visual tension, while the hot colours favoured by the artist underscores the artificial or contrived nature of the images.

In an article written in 1971 Joseph Mashek saw in this suite of prints and in Abrahams' contemporary sculptural work a partly satirical exposure of the stylistic underpinnings of a still current concept of gardening:

Like the neatly clipped, slightly chilling ‘good neighbour’ hedges in ‘Privacy Plots’ (his recent suite of prints) and like the mysterious postcard-deadpan prints of bulging bourgeois herbage executed earlier [‘Garden Suite’], Abrahams' new sculpture concerns itself with the special style of gardening called the ‘gardenesque’. Successor to simpler, merely ‘picturesque’, types, this was an overstuffed, Biedermeier, gaudily massed and raucously colored approach to gardening whose invention and development was the responsibility of the Victorian age ... It is no accident that Abrahams' own reading in the literature of garden art centers on the Victorian period, on John Claudius Loudon's ‘The Ladies’ Companion to the Flower Garden', of 1834, and other works of that order. This edges on Pop sensibility in a curious way, by exposing the vulgarity of assumed good taste and revealing it as style. The local governments, commercial firms, and suburban bourgeoisie, thinking that they know perfectly well how gardens tastefully ought to look, are caught with their aesthetic pants down. Like true Pop, it isn't mere satire either, and with all serious gardening it shares a sense of being a journey into a private world.

(‘In the Gardens of the Mind’, Arts Magazine,

vol.45, no.4, Feb. 1971, p.31)

Mashek (p.33) pointed to a certain ambivalence in Abrahams' images of suburbia. ‘There is ... a post-Pop tendency at work, as if these harmlessly inane visions of a suburban Arcady were for us as observing outsiders beyond criticism. They seem like they could have been built by people who had terrible taste but who were nevertheless close friends’. And yet, at the same time, he wrote, Abrahams' images often suggested a threatening or lonely environment.

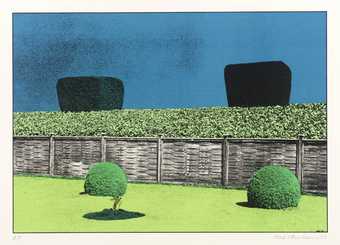

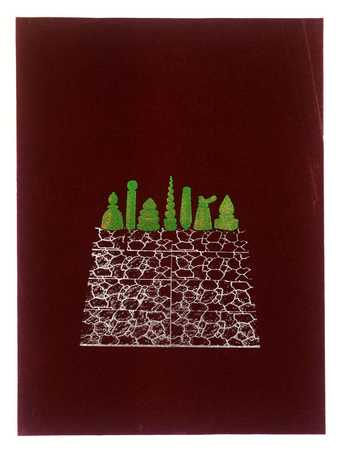

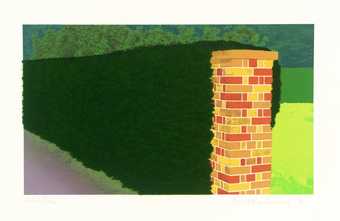

P11105 Privacy Plots V: Hedge and Street 1970

Screenprint and flock fibre 400 × 595 (15 3/4 × 23 3/8) on Crisbrook wove paper 568 × 784 (22 3/8 × 30 7/8)

Inscribed ‘Ivor Abrahams 70’ below image b.r. and ‘Artists Proof.’ below image b.l.

Repr: Cologne exh. cat., 1973, p.85, fig.14 (unspecified impression)

‘Hedge and Street’ is dominated by an ornamentally shaped, flocked green hedge. In front is a bright green lawn and a path of crazy paving, printed in grey, mauve and blue metallic inks. This crazy paving, a recurring motif in Abrahams' work (see previous entries on P11099-P11100), alluded to the role of artifice in gardens. Behind is a street scene in which the photographic nature of the source image remains very clear.

In the Cologne catalogue this print is described as having required fifteen printings and one flocking, though the hedge has two layers of flock. In conversation Abrahams described this print as the least successful of the suite, saying that he had probably ‘run out of ammunition’ when he came to make this work.

Published in:

Tate Gallery: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions 1986-88, London 1996

Explore

- architecture(30,960)

-

- garden structures(1,939)

- residential(5,553)

-

- house(2,675)

- townscapes / man-made features(21,603)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- photographic(4,673)

You might like

-

Ivor Abrahams Garden Suite I

1970 -

Ivor Abrahams Garden Suite III

1970 -

Ivor Abrahams Garden Suite IV

1970 -

Ivor Abrahams Garden Suite V

1970 -

Ivor Abrahams Garden Emblems I

1967 -

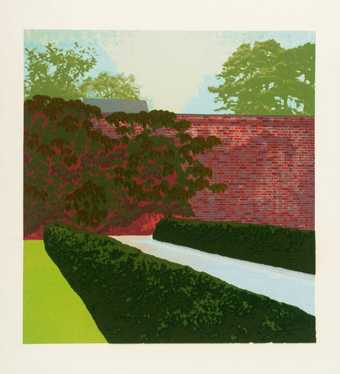

Ivor Abrahams Privacy Plots I: Brick Wall

1970 -

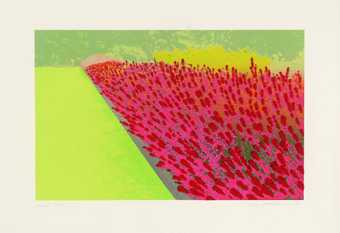

Ivor Abrahams Privacy Plots II: Flower Garden

1970 -

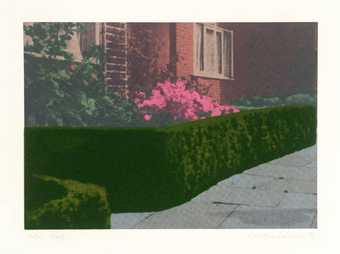

Ivor Abrahams Privacy Plots III: Suburban Hedge

1970 -

Ivor Abrahams Privacy Plots IV: Gate Post and Hedge

1970 -

Ivor Abrahams Arch II

1971 -

Ivor Abrahams Arch IV

1971 -

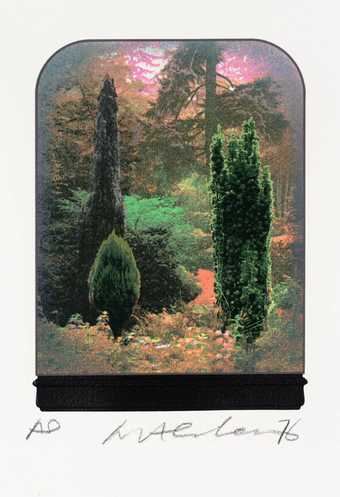

Ivor Abrahams The Domain of Arnheim

1976 -

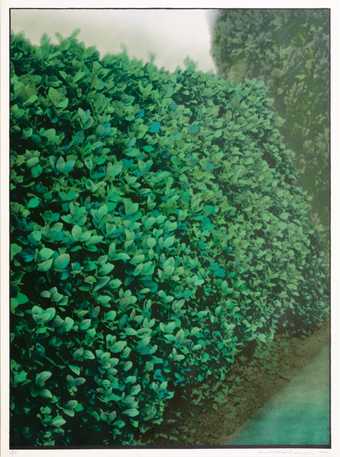

Ivor Abrahams Hedges I

1977 -

Ivor Abrahams Oxford Gardens V

1977 -

Ivor Abrahams Oxford Gardens VIII

1977