Not on display

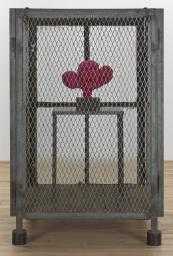

- Artist

- Absalon 1964–1993

- Original title

- Cellule No. 1

- Medium

- Wood, fibreboard, fabric and fluorescent lights

- Dimensions

- Unconfirmed: 2450 × 4200 × 2200 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the Patrons of New Art through the Tate Gallery Foundation 1997

- Reference

- T07222

Summary

This structure is the first in a series of six full-scale prototype units, intended for single-occupancy living, that Absalon designed for his own use. Made from plywood, the unit is painted completely white on both the inside and outside. Its smooth arched form, resembling a vault, features two rectangular openings – a door in the front and a horizontal window in the rear – and is lit from above by fluorescent lights hanging from the gallery ceiling. The Israeli artist planned to install final versions of these residential ‘cells’, as he called them, equipped with electricity and running water, in six major cities around the world, corresponding to his exhibiting activities. The completed inhabitable cells would, Absalon declared, provide him with ‘a solution to living in society’ (Absalon, ‘Lecture’, 1993, p.260).

Cell No.1 was intended for Paris. Absalon explained that each cell’s architecture responded to its planned urban destination, commenting on this work: ‘I took my inspiration from a Roman tomb, and as I think Paris is a very classical city it should suit that location perfectly’ (Absalon, ‘Lecture’, 1993, p.259). The cell shares with the other prototypes in the series a modest scale, stark white surfaces and an economic approach to the artist’s everyday needs. Into an area of twelve square metres, the structure squeezes a kitchenette, a work-space (consisting of a table, chair and bookshelf), a closet that supports a mattress for sleeping, and a washroom in which the toilet and shower are combined over a gridded drain. The exhibition of these prototype cells allows for visitors to explore their interiors freely, although it was Absalon’s intention that the completed cells would only be visited in his presence by a single person at a time.

For each cell, both the dimensions of the appliances and the minimal spaces between them were carefully calculated according to the proportions of the artist’s own body. Absalon elaborated on the significance of this architectural system in a statement that accompanied the cells’ first exhibition in 1993:

The Cell is a mechanism that conditions my movements. With time and habit, this mechanism will become my comfort … The project’s necessity springs from the constraints imposed … by an aesthetic universe wherein things are standardized, average … I would like to make these Cells my homes, where I define my sensations, cultivate my behaviours. These homes will be a means of resistance to a society that keeps me from becoming what I must become.

(Absalon, Cellules, 1993, unpag.)

Although Absalon intended that the cells would offer an alternative mode of private urban existence, he took care to emphasise that the homes were not meant to be ‘utopian’. In doing so, he implicitly rejected the collective social ideals evoked by the cells’ clean lines and pure white exteriors, which are reminiscent of modernist design, and the particular history of the place where they were made: Absalon’s studio in Paris occupied a building designed by the modernist architect Le Corbusier in the early 1920s. The curator and writer Nina Möntmann has also suggested that an opposition to collective social aims underpinned Absalon’s plan to install the completed Cell No.1 on the esplanade of Les Olympiades – a 1970s high-rise residential estate in Paris’s thirteenth arrondissement considered to epitomise modernist theories of communal living (Nina Möntmann, ‘“If an Idea is Good for Two People, it is a Bad Idea”: On the Individual Spatial Economy of Absalon’s Cells’, in Pfeffer 2011, pp.293–9).

The plan to install this work in Les Olympiades was never realised. Cell No.1 is the only cell in the series to have been executed in a fully functioning form by the artist before he died from AIDS in 1993 (an inhabitable version of this prototype resides in the collection of the Musée d’Art Contemporain in Marseille). While Absalon was reluctant to have his illness determine the interpretation of his work, the fragility of these smooth plywood structures, intended to be located within frenetic urban centres, may be seen to hold a particularly personal resonance: ‘once I am no longer here,’ the artist explained, ‘these houses will disappear because of their ephemeral nature, they are really constructions related to my life, to me, only to me’ (Absalon, ‘Lecture’, 1993, p.258).

Further reading

Idit Porat (ed.), Absalon, exhibition catalogue, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv 1992.

Absalon, Cellules, exhibition catalogue, Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris 1993.

Absalon, ‘Lecture: École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris, May 4 1993’, reprinted in Susanne Pfeffer (ed.), Absalon, exhibition catalogue, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Cologne 2011, pp.255–73.

Debra Lennard

January 2014

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Cell No.1 is one of six structures modelled on human dimensions that Absalon designed for various major cities around the world. He intended to inhabit these cells himself, maintaining a consistent lifestyle within a nomadic existence. The structure recalls the simple forms of modernist architecture. It also refers to the impact of technology in the twentieth century, mimicking a space capsule or nuclear shelter. Absalon explained that the cells embodied a 'desire for a perfect universe', not in the revolutionary or utopian sense, but as a personal space for solitude and shelter.

Gallery label, August 2004

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- architecture(30,960)

-

- periods and styles(5,198)

-

- modernist(155)

- residential(5,553)

-

- cell(4)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

- purity(43)

- social comment(6,584)

-

- industrial society(425)

You might like

-

Louise Bourgeois Single II

1996 -

Louise Bourgeois Cell XIV (Portrait)

2000 -

Louise Bourgeois Couple I

1996 -

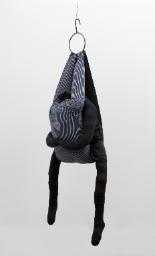

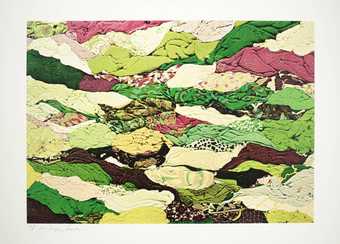

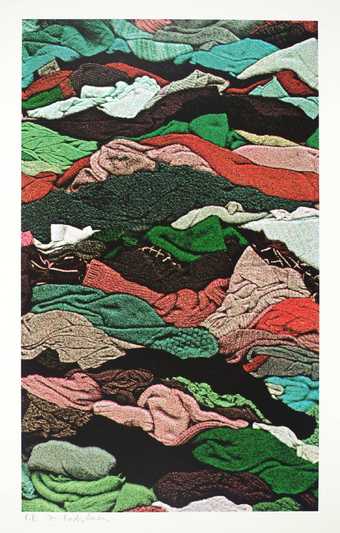

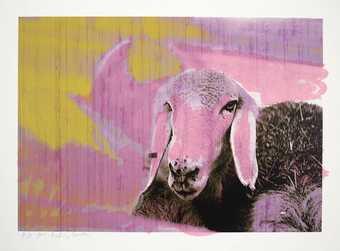

Menashe Kadishman Cloths B

1979 -

Menashe Kadishman Upright Rags B

1979 -

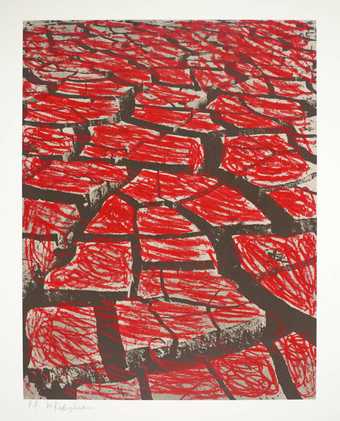

Menashe Kadishman Cracked Earth B

1979 -

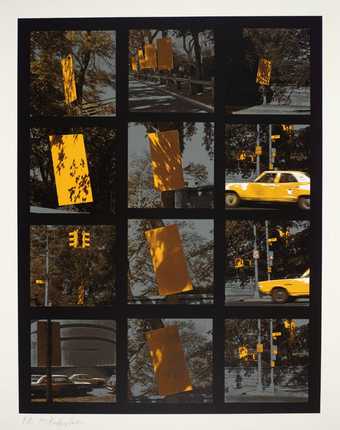

Menashe Kadishman New York A

1979 -

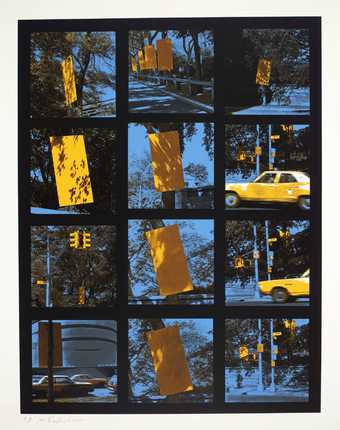

Menashe Kadishman New York B

1979 -

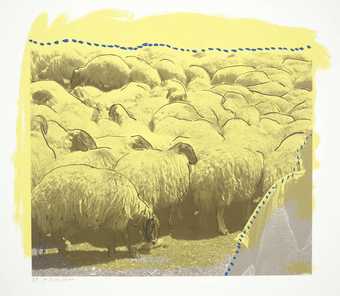

Menashe Kadishman Sheep A

1979 -

Menashe Kadishman Sheep Head B

1979 -

Gilad Ophir Shooting Targets

1997 -

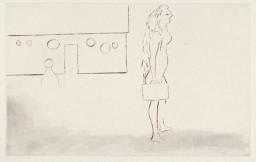

Louise Bourgeois Woman with Suitcase

1994 -

Marc Camille Chaimowicz Le Désert ...

1981 -

Christian Boltanski The Reserve of Dead Swiss

1990 -

Louise Bourgeois Mamelles

1991, cast 2001