Not on display

- Artist

- Dia al-Azzawi born 1939

- Medium

- Ink and wax crayon on paper mounted on canvas

- Dimensions

- Displayed: 3000 × 7500 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by Tate Members, Tate International Council, Tate’s Middle East North Africa Acquisitions Committee and the Basil and Raghida Al-Rahim Art Fund 2014

- Reference

- T14116

Summary

Sabra and Shatila Massacre 1982–3 is a monumental work in ball point pen and pencil on paper, constructed in six sections and affixed to canvas for support. The work was made in response to the massacre by Christian Lebanese Phalangists of Palestinian refugees in the camps in Beirut, Lebanon, between 16 and 18 September 1982, while the camps were under the guard of the Israeli Defence Force. Working from imagination, al-Azzawi has delineated the scenes of chaos and horror in the Sabra and Shatila camps in a semi-abstract style, with a shallow perspective.

Speaking with Tate curator Jessica Morgan on 27 April 2011, the artist explained that his decision to depict the scenes of the massacre was inspired by reading the essay Quatre Heures à Chatila (Four Hours in Shatila) by French writer Jean Genet (1910–1986). Genet was in Beirut when the massacres took place and was one of the first observers to enter the camps thereafter. He wrote: ‘A photograph doesn’t show the flies nor the thick white smell of death. Neither does it show how you must jump over the bodies as you walk along from one corpse to the next … A barbaric party had taken place there.’ (Jean Genet, ‘Quatre heures à Chatila’, Revue d’études palestiniennes, vol.6, Winter 1983, pp.3–19.) Al-Azzawi explained that the drawing was made in his home in Highgate, London, over a number of months, during which time he worked solely on this project. Stylistically it owes a debt to Pablo Picasso’s Guernica 1937 (Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid), although al-Azzawi’s drawing is considerably more claustrophobic; the vast expanse of paper offers no respite from the horror of the scene, being densely packed with body parts, architectural and domestic details, images of animals and bombs.

Markedly different to al-Azzawi’s normally colourful paintings and relief sculptures from this time, the use of mainly black and grey tones in Sabra and Shatila Massacre is interrupted by moments of colour used to depict the earthy tones of the ground or the red of blood. This restrained use of colour makes its appearance all the more jarring in the massive expanse of the drawing. The style of this work relates more closely to the print and book illustrations by the artist, practices that have consistently been major parts of his output. In 1976 al-Azzawi made a series of drawings for a book about the destruction and loss of life at the Tel al-Zaatar Palestinian refugee camp in that year, similarly calling on literature to mediate the violence of the event. On his use of literature, and in particular poetry, as a catalyst for his work al-Azzawi has said: ‘The poem is very important. It gives the artist a great deal in terms of atmosphere. I wanted to paint the tragedy of Tel al-Zaatar. I started, but later I turned to the poems, they gave me the inspiration I needed.’ (Quoted in http://www.azzawiart.com/essays_by_dia.php?id=4, accessed 1 August 2011.) Al-Azzawi has also produced illustrations to accompany collections of Arab poetry (‘Hymne de corps’ 1979, for example), that share the same stark visual language and predominant use of black and grey tones as Sabra and Shatila Massacre. Al-Azzawi’s work has consistently addresed the political events of the Middle East and previous series of works have included over forty gouaches from the 1970s reflecting on his military service fighting the Kurds. Sabra and Shatila Massacre represents the most significant and monumental attempt by the artist to address the turmoil in the region.

Dia al-Azzawi was born in 1939 in Baghdad, Iraq. He is considered one of Iraq’s most influential living artists and a leading figure for the emergence of modern painting and printmaking in the country. In 1969 he wrote and published the manifesto ‘Towards the New Vision’, outlining the ambitions of himself and his contemporaries who were incorporating a semi-abstract language in works that drew on a Sumerian, Syrian and Islamic heritage. In the early 1970s, with Shaker Hassan a-Said (1925–2004) and Rafa al-Nasiri (born 1940), he established what became known as the One Dimension group which promoted the idea of an Iraqi or Arab identity through art and the use of calligraphy in modern painting.

Due to the scale of Sabra and Shatila Massacre, it has rarely been exhibited, aside from three years between 1983 and 1986 when it was on display at the National Council for Art and Culture, Kuwait. Given its significance in al-Azzawi’s work, however, it has been widely reproduced in catalogues devoted to his work and modern Arab art.

Further reading

Dia Azzawi, exhibition catalogue, Institut du monde arabe, Paris 2001, reproduced p.82.

Nada Shabout, Modern Arab Art: Foundation of Arab Aesthetics, Gainesville 2007.

Saeb Eigner, The Art of the Middle East: Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World and Iran, London and New York 2010, pp.130–1, reproduced.

Jessica Morgan

August 2011

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

This work was made in response to the massacre of civilians at the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in Beirut, Lebanon in September 1982. Those killed were mostly Palestinian. The violence was carried out by a militia associated with a Christian Lebanese right-wing party. The camps were under the guard of the Israeli Defence Force. Al-Azzawi worked on the drawings over several months, creating no other work. In its subject matter and scale, the work is related to Pablo Picasso’s Guernica 1937, a large painting that brought attention to the violence of the Spanish Civil War (1936–9).

Gallery label, August 2019

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- figure(2,270)

- residential(5,553)

-

- camp(8)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

- violence(331)

- chair(915)

- actions: expressive(2,622)

- child(1,324)

- cities, towns, villages (non-UK)(13,323)

- Lebanon(145)

- birth to death(1,472)

-

- death(685)

- refugee(1,995)

You might like

-

Sir Don McCullin CBE Palestinian Refugees Fleeing East Beirut Massacre

1976, printed 2013 -

Sir Don McCullin CBE After the Massacre of Sabra Camp in Beirut

1982, printed 2013 -

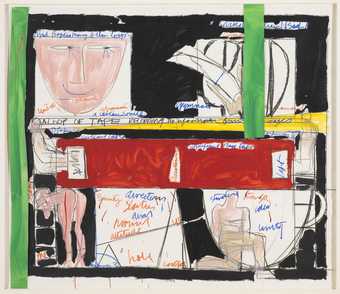

Bruce McLean Study towards the Object of the Exercise

1978 -

Art & Language (Michael Baldwin, born 1945; Mel Ramsden, born 1944) Gustave Courbet’s ‘Burial at Ornans’; Expressing a Sensuous Affection .../Expressing a Vibrant Erotic Vision .../Expressing States of Mind that are Vivid and Compelling

1981 -

Terry Setch Once upon a Time there was Oil III, Panel I

1981–2 -

Art & Language (Michael Baldwin, born 1945; Mel Ramsden, born 1944) Index: The Studio at 3 Wesley Place, in the Dark (VI), Showing the Position of ‘Embarrassments’ in (IV)

1982 -

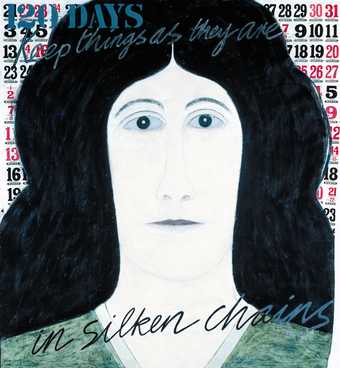

Ian Breakwell Keep Things as They Are: In Silken Chains

1981 -

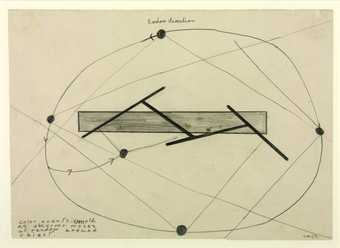

Stephen Willats Drawing for Construction

1963 -

Shirazeh Houshiary The Angel of Thought

1987 -

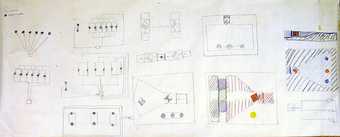

Stephen Willats Worksheet for Visual Automatic No.5, No.4

1965 -

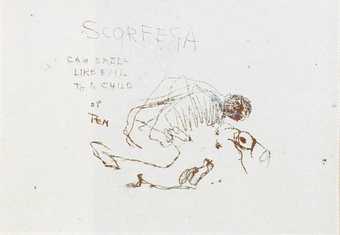

Tracey Emin Scorfega

1997 -

Mary Beth Edelson Selected Wall Collages

1972–2011 -

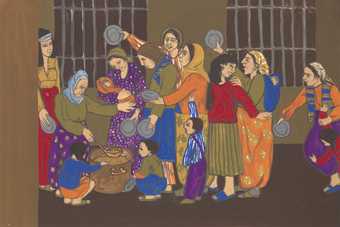

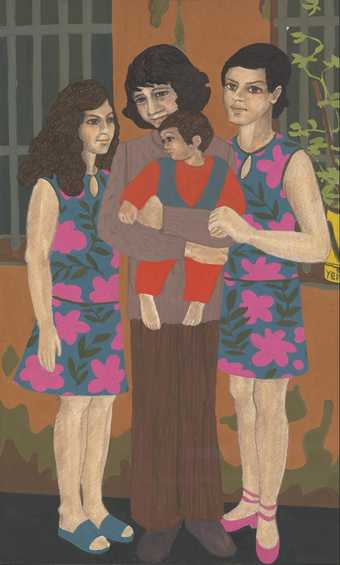

Gulsun Karamustafa Prison Paintings 9

1972 -

Gulsun Karamustafa Prison Paintings 11

1972 -

Gulsun Karamustafa Prison Paintings 17

1972