Not on display

- Artist

- Edward Allington 1951–2017

- Medium

- Graphite, ink and acrylic paint on paper on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 1830 × 2440 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the Weltkunst Foundation 1987

- Reference

- T04910

Catalogue entry

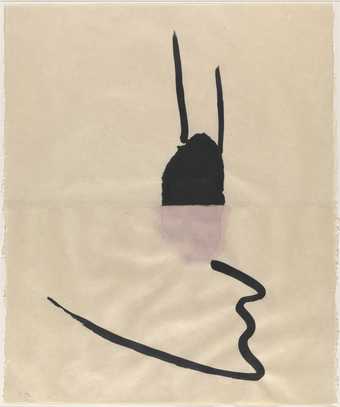

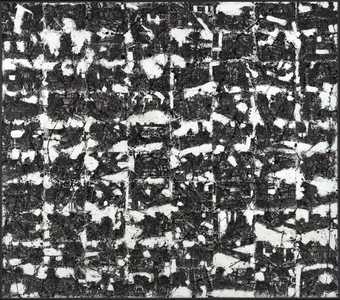

T04910 Seated in Darkness 1987

Pencil, ink and acrylic emulsion on off-white, printed wove paper, inscribed by other hands in ink and laid on canvas 1830 × 2440 (72 × 96)

Signed ‘Edward | Allington | 1987’ and inscribed ‘SEATED IN DARKNESS | E.A.87 D.15’ on back of canvas t.r.

Presented by the Weltkunst Foundation 1987

Prov:

Lisson Gallery 1987; bt Marlene Eleni 1987 by whom sold to Weltkunst Foundation

Exh: Edward Allington, Marlene Eleni Gallery, April 1987 (no cat., no number)

Lit: Mary Rose Beaumont, ‘Edward Allington’, Arts Review, vol.39, 10 April 1987, pp.234–5, repr. Arts Review Exhibition Guide, April 1987, [p.4]; Tate Gallery Report 1986–8, 1988, p.95, repr. (col.)

At the centre of ‘Seated in Darkness’ is a grouping of what appear to be architectural fragments. A large slab floats above the flooring. Beneath it are broken or roughly hewn stone forms, which also appear to hover above the ground. Resting on, or just touching the slab, are two separate piles, consisting of plain rectilinear blocks and ornamental scrolls, some decorated with leaf motifs. The function of these forms is not apparent, and the grouping itself gives the impression of being unstable: a large semicircular piece appears to topple backwards. The stone forms cast black shadows, but their shape is not consistent with that of the forms. On three sides are plain white walls with doorways leading into apparently identical rooms. An invented form, curving but angled at the centre, is propped against the right-hand wall, casting a shadow that appears grey on the wall and black on the floor.

‘Seated in Darkness’ is painted with white emulsion paint and black ink, producing shades of grey where the two overlap. The support consists of sheets of paper taken from a ledger used by an Avis car hire firm in Greece and glued in regular rows on the canvas support. The words and columns of figures written on the sheets in blue biro can be seen clearly in the area of the flooring. Some figures and words, which are in Greek, can also be seen in places where the emulsion is particularly thin or has been partly absorbed by the paper.

In conversation with the compiler on 26 May 1994 the artist talked about how he made T04910. All Allington's canvases are of standard proportions, 3 feet × 4 feet, 4 feet × 6 feet, or, as in this case, 6 feet × 8 feet. According to the artist, the canvas would have been stretched either by himself or, possibly, by an assistant who was then working in his studio. Using PVA adhesive, Allington glued sheets of ledger paper onto the canvas surface, starting at the top and trimming the last row to the size of the canvas. Each sheet measures approximately 285 × 445 mm and is printed with grey, blue and pink lines. There are seven overlapping rows of six sheets. The blueness of the writing in biro has been heightened by the adhesive, and the biro ink has bled slightly in places. The resulting papered surface is not completely smooth: some sheets have rough edges where they were torn from the ledger, and in many places the edges had lifted off the surface before the artist began to paint. It is extremely rare for the artist to make preparatory drawings, but in this case he made six works, which are discussed below. On the papered canvas Allington first sketched the outlines of the image in pencil. Using black Quink ink, he then drew the main outlines of the forms, the shading on the architectural elements and the shadows. As he worked, he altered the image in places, leaving the lines of the original pencil drawing plainly visible (see, for example, the area by the stone form at the lower left). He then applied ordinary household emulsion. Some words and figures in the ledger sheets remained visible through the layer of emulsion, but this was a random effect which the artist did not seek to control. He continued to work on the image in black ink. Where the emulsion was still wet, the lines appeared pale grey, and where the emulsion was drier the lines were correspondingly darker. To achieve very dark blacks, the artist let the ink evaporate and become viscous before applying it. In the black shadow in the centre of the image there is some mottling, which was caused by accidental staining of the paper by olive oil before the artist acquired the ledger. The oil also had the effect of making the writing in blue biro in the same central area appear turquoise. Allington signed and titled the work on the back, adding ‘D.15’. This signifies that it was the fifteenth drawing to be entered in his record book for 1987, not that it was the fifteenth drawing to be executed in that year.

From the mid-1970s to the early 1980s Allington used ordinary graph paper in many of his drawings. He chose this paper, he said, because it helped establish the picture plane and because he liked the fact that it was a commonplace, modern type of material. In ‘Dog Instructions’, 1976 (repr. Drawing Towards Sculpture, exh. brochure, Institute of Contemporary Arts 1984), the grid of the graph paper serves as a sympathetic ground for the illusionistically drawn geometric forms. In a later work, ‘Ideal Standard ‘Forms’, 1980 (repr. ibid.), the graph paper has a more active role in the composition: surrounded by white walls, it denotes flooring, a ‘real’ element supporting the imagined forms drawn upon it. This function can be seen as anticipating that of the areas of exposed ledger paper in T04910.

Allington recalled in conversation that it was in 1979, in the period leading up to his making of ‘Ideal Standard Forms’, 1980 (T05214), a sculpture of central importance in his career, that he began to look for other sorts of paper to use in his drawings. As a student wanting something that would serve as a toolbox, he had once looked in a skip which had steel deed chests of the sort that solicitors use. He took one that had a key in it, oiled the lock and made it work, and found, to his surprise, that it contained the entire documentary history of a particular family. He did not keep these papers, but later, in 1979, he remembered this incident. In conversation with the compiler he described, the horror, if you like, of coming across some of these incredibly grand descriptions of some family's life, where all that remained were all these documents in which people had not recorded anything to do with their emotional life - they [the papers] were just ciphers - and yet you got a sense of them [the people]’. He began to look out for old ledgers, searching through skips and asking friends and acquaintances. He discovered that ledgers are relatively hard to find: they are kept by people only as long as it is thought that the information they contain might be useful. If they are preserved, it is often simply for their leather bindings. However, he began to accumulate reserves of ledger books, which he has used in his works on paper through the 1980s to the present day.

In conversation Allington explained that he liked the fact that the information contained in such ledgers was a coded record of peoples' lives, once useful but now redundant. This was related to his concern to explore in his work the present remains of the past, in all their sometimes banal, materiality, and to reveal their limitations as guides to the past. Allington said he was attracted to the feel and look of the ledgers, and the particular quality of the paper and the ink; but what mattered most was that the paper was part of contemporary life. ‘It's part of a fascination with the things that are ordinary. A lot of the things that are listed in them are the mundane way everyone is recorded in western society, in account books, in insurance ledgers. It's all been computerised now, but people still keep ledgers.’

Allington has used many different types of ledgers, and generally allows the particular identity of the paper to remain clearly visible. An early example of Allington's use of ledger paper, ‘Towards Some Interesting Dooms’, 1983 (repr. ibid.), for example, has sheets of paper headed ‘Amalgamated Society’. ‘Between the Horns of the Snail’, 1984 (repr. Edward Allington, exh. cat., Fuji Television Gallery, Tokyo 1988, no.14 in col.) uses paper with printed Japanese writing, while ‘Decorative Fragments no.2’, 1985 (repr. ibid., no.16 in col.) has hand written arabic on pages headed ‘Ledger of Deposit’. It is important to Allington that the ledgers he uses are all twentieth-century. However, he is aware that such ledgers may become outmoded soon. ‘I have a horror of the work being nostalgic’, he said. ‘Hence, I have serious worries about continuing with this way of working’.

The particular paper found in T04910 was taken from a ledger used by an Avis car hire firm in Corfu, run by a relation of a friend of the artist. Allington asked his friend to bring the ledger back with him from Greece, and it was on the journey that olive oil was spilled on the book. In conversation with the compiler, the artist said that he was not concerned with the subject matter of the ledger paper, nor did he understand any of the Greek words. No particular relationship between the modern Greek script and the classical nature of some of the architectural elements was intended, nor was there meant to be any irony in the relationship between car hire and the chariot-like configuration of the stone forms. The artist explained: ‘I never premeditate meanings or quotations, to add them up into a narrative. I am not interested in that at all. You get things that match up, but it is a kind of fortunate coincidence. It is not really in my domain. It is in the spectator's domain’.

The inspiration for ‘Seated in Darkness’ came from a particular print by Piranesi (1720–78), an artist famous for his etchings of the ruins of classical Rome and architectural fantasies. Allington had been interested in Piranesi for some years: in a leaflet accompanying the exhibition ‘The Prisoners of the Sun’ (Exe Gallery, Exeter 1982) he wrote, ‘I feel I can now confess to some form of figuration, hopefully almost hopelessly inaccurate and now begin to see similar meaning and concerns in the earlier work, and so begin to realise that my interests are also with Piranesi, David and Ingres rather than Cézanne and his apples’. Allington identified the work of Cézanne and the modernist tradition in art with an attempt to record some visual truth about the world, and felt that the earlier masters he named offered, in a humble, unselfconscious way, a more personal meditation on art and its traditions. It was in this period that Allington decided he needed an anonymous drawing style. He studied the hatching techniques of old etchings and engravings, admiring, in particular, the works of Piranesi and William Hogarth (1697–1764). Allington's interest in the latter's prints and writings can be seen in the series of drawings entitled ‘Analysis of Beauty (After Hogarth’, 1985 (repr. Edward Allington: Bronzes and Drawings, exh. cat., Lisson Gallery 1985, pp.21, 23, 25, 27). The work of these two artists was also an important source for the architectural forms, in particular, the ‘S’ shaped scrolls, found in Allington's drawings from the early 1980s.

In conversation with the compiler Allington described how he came across the print that inspired T04910 and his reaction to it:

I first saw the print in a little gallery that used to be near to the British Museum. They had an exhibition of Piranesi prints. I went in and had a thumb through them all. I looked round the show, and asked if they had any other prints, and I looked through them. My level of interest was high, but not that high. I wanted to look at them, but when I came across this particular print which was in a drawer, I felt that there was something within it that I desperately needed for my work. A kind of darkness that he got in that print by the simple means of the hatching. I could not work out how he had got the sense. When I saw the print, it described the form accurately. The print is probably one of his more mundane ones. It is a bit like a postcard of an archaeological object that he was producing to sell to tourists, more or less. It describes the throne, it does not exaggerate it - it is not a ‘Piranesi’ Piranesi. But even so, even though it was an attempt to describe this object using this technique, I felt it had this sense of sadness, I suppose, a darkness and loss.

He was not interested, however, in any pathos associated with the image of the empty throne; it was ‘something much blunter’ that attracted him. He added:

I have made a crude attempt to describe whatever that feeling was, but the crucial thing was that I could not describe what it was. I could not say that this print looks a bit sad, or maybe because it is a bit dark in this area or whatever, I could not quite understand what it was. I came to understand it not in intellectual terms, or in terms that I can articulate using words. I can understand it in terms of things that I can do with my hands.

The untitled print in question is taken from a series entitled Vasi candelabri cippi sarcophagi tripodi lucerne ed ornamenti antichi disegnati ed incisi dal cav. Gio. Batt. Piranesi publicati l'anno MDCCLXXIIX and is listed as no.684 in Henri Focillon, Giovanni-Battista Piranesi: Essai de catalogue raisonné de son oeuvre, Paris 1918. Allington bought the print at Weinreb Architectural Gallery, which at the time had premises in both Museum Street, near the British Museum, and Sackville Street in central London. The etching, which measures 39 × 53 cm, shows, in the centre, a three-quarter view of an antique throne, facing right, and, in the top right-hand corner, a smaller back view of the throne. Below it is a marble vase, decorated in places with scallop shell motifs. The text inscribed in a scroll in the bottom left describes the throne as having been found in the time of Pope Paul III in the Roman Forum, in the area know as the Rostrum. The throne combines plain geometric shapes with areas of ornate decoration, and is made up of two distinct parts. The seat itself has a semi-circular back piece, and rests on two naturalistically carved dogs facing towards the rear. In front is a separate footstool, the sides and underneath parts of which are decorated with floral and leaf motifs on ‘S’ shaped vertical scrolls. Beneath it is a low rectilinear slab, in front of which are two further decorated horizontal ‘S’ shaped scrolls. These separate elements rest on a rectlinear slab. Piranesi added faintly drawn herbiage at the bottom of the image, to provide some sort of setting, albeit unconvincing, for the throne. In conversation with the compiler on 23 June 1994 Allington said he had been particularly attracted by the fact that the throne, with its dark shadow, crisply drawn in parallel shading lines, appears to float above the ground, divorced from its setting.

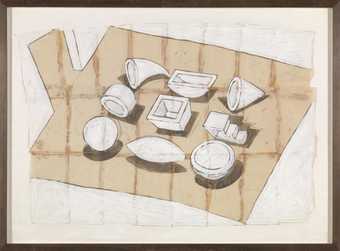

Using sepia ink, Allington made six drawings based on the Piranesi print. These drawings, all of which are currently in the artist's collection, were exhibited with T04910 at the Marlene Eleni Gallery in April 1987, and were numbered and titled before the show. The numbers Allington gave the works, however, do not record the order of their making, and he cannot now recall the sequence. The following listing, however, may approximate their order:

1. ‘After Piranesi VI’ 1986

Ink on thin wove paper 267 × 210 (10 1/2 × 8 1/4)

Inscribed ‘Edward | Allington 86’; various inscriptions in another hand

This drawing, identified in the artist's record book as ‘EA.87.D.14’, appears to be the first of the series as it is the only one to represent the throne facing to the right in the manner of the Piranesi print. In conversation on 23 June 1994 Allington explained that in 1979–80 he had decided on a set of conventions which would govern his works on paper; one of these was to make the vanishing point lie to the right, which he felt was traditional and natural to him as he is right-handed. All the other drawings, and T04910 itself, show the throne facing to the left.

The ink drawing shows the seat part of the throne, with its remarkable semi-circular back. The two supports in the original print are replaced in the drawing by a single, central support. The dogs are replaced by a block, decorated only by a flat ‘S’ form. This plain ‘S’ shape is echoed in the edge of the three-dimensional scroll in front of the seat in T04910. In both this drawing and in T04910 the artist retained from the original Piranesi print the scalloped base which sits on the large slab.

In the preparatory drawing the base casts a dark shadow beneath it and appears to float a small distance above the ground. The unlined paper used for this drawing was taken from a receipt book that Allington found at the Abbaye Royale de Fontevrault in the Pays de la Loire. Allington visited the Abbaye in 1986 when invited to participate in ‘3ème Ateliers Internationaux’ held there. The records of the Abbaye, which had been a prison until recently, were in disarray and Allington was allowed to take away with him about fifty ledgers. The sheet of paper used in this drawing is dated ‘13/12/56’, and the words, written in blue biro, list in French articles of clothing and possessions taken from a particular prisoner on admission.

2. ‘After Piranesi II’ 1986

Ink on printed wove paper 264 × 419 (10 3/8 × 16 1/2)

Inscribed ‘Edward Allington | 86’ b.r. and ‘after Piranesi’ b.l.; various inscriptions in another hand

This drawing, identified in the artist's record book as ‘EA.87.D.10’, appears to be the second drawing in the series, as it is the only other one to be dated 1986. The artist has said that he almost certainly would have signed and dated the work shortly after its completion. Therefore, although the drawing is quite developed, the artist believes its date is probably correct and that it therefore came relatively early in the sequence.

The image focuses on the footstool alone. The direction of the curves of the scrolls on the front is the same as in the Piranesi; in T04910 Allington reversed the direction of these scrolls. The flat section in front of the footstool in the Piranesi is raised and reduced in its relative dimensions. An area of black shadow separates it from the supporting slab, which in turn appears to float above the ground. Here, as in the other drawings, it is the shadow alone which establishes the existence of the ground.

The paper is a double page taken from an official ledger with ten vertical columns relating to the removal and return of the personal possessions of prisoners held at the Abbaye de Fontevrault. Completed in blue biro, the sheet is dated 13 December 1956.

3. ‘After Piranesi V’ 1987

Ink on wove paper 267 × 210 (10 1/2 × 8 1/4)

Inscribed ‘E. Allington 87’ b.l. and ‘after Piranesi’ t.l.; various inscriptions in another hand

The image of this drawing, which is identified in the artist's record book as ‘E.A.87.D.13’, is similar to that of ‘After Piranesi II’. The footstool, however, is shown from a slightly higher elevation, and the drawing is marginally less finished. The supporting slab appears roughly hewn, as in T04910, rather than perfectly straight as in the original Piranesi, or even ‘After Piranesi II’.

The paper is the same type of thin copy paper used in the first drawing, and was also dated on 13 December 1956.

4. ‘After Piranesi IV’ 1987

Ink on printed wove paper 267 × 210 (10 1/2 × 8 1/4)

Inscribed ‘Edward | Allington | 87’ b.r.; various inscriptions in another hand

This drawing, identified in the artist's record book as ‘E.A.87.D.12’, shows the seat alone. The image differs from that of ‘After Piranesi VI’ in a number of small ways. The shape linking the semi-circular back support to the square part of the seat ends in an ornamental scroll; two separate scroll forms, decorated with leaves but, nonetheless, quite thin, act as the front legs of the chair; the base is a thin, relatively small rectangle. Like ‘After Piranesi IV’, however, the seat's shadow falls, unusually, to the left.

The paper, which appears to be torn from a ledger, bears the printed headings ‘Ministère de l'Intérieur | Administration pénitentiaire’, ‘République Française’ and ‘Minute’. This official memorandum is dated 25 August 1905, and came from the same source as the other papers used in this series of drawings.

6. 5. ‘After Piranesi III’ 1987

Ink on printed wove paper 349 × 451 (13 3/4 × 17 3/4)

Inscribed ‘E. Allington 87’ b.r.; various inscriptions in another hand

This drawing, identified in the artist's record book as ‘E.A.87.D.11’, shows both the chair and footstool sections of the throne, resting on the slab-like base. As in T 04910, the semi-circular back support appears to tumble off the back edge. The seat has two separate scrolls on its front, and sits on a scallop-edged base. The dark shadows create the impression that all the elements are floating.

The paper is an accounts sheet, headed ‘Recettes’ and ‘Paiements’. Ruled with grey, red and blue lines, it is similar in type to the paper used in T04910.

6. ‘After Piranesi I’ 1987

Ink on printed wove paper 264 × 419 (10 3/8 × 16 1/2)

Inscribed ‘Edward Allington | 87’ b.r.; various inscriptions in another hand

This drawing, identified in the artist's record book as ‘E.A.87.D.9’, is similar to the previously mentioned drawing. However, whereas the footstool in ‘After Piranesi III’ was shown as clearly smaller than the seat, it appears in this work to be slightly higher. This change in the relative proportions of the elements suggests that this drawing is the closest in spirit to T04910. Unlike the finished work, however, the front of the seat in the drawing has two separate scrolls; there is no scalloped base for the seat; there are no fragments around and underneath the slab; and, as in all the preliminary drawings, there are no walls or indication of flooring.

The paper, a double ledger sheet for the recording of prisoners' possessions, is of the same type as used in ‘After Piranesi II’, and is dated 13 December 1956.

In conversation with the compiler on 26 May 1994 the artist recalled his obsession with this particular image. After buying the Piranesi print, he hung it in his studio for a few months. Instead of diminishing, his interest in the print grew to the point where he felt he had to respond. Working ‘manically’, he made the series of drawings over a period of a few weeks. To make this number of drawings was untypical: ‘Usually the gestation period will take longer. Often there will not be as many drawings, if there are any at all. The thing will start to form more concretely in my mind, and I will work it out on the canvas with some notes in notebooks, where I'll sort out problems. But this was a particularly problematic image’. Allington said that the first few drawings were close to the original print, but became less so as he worked through the problems posed by the image. ‘I felt that there was something in the Piranesi that I wanted - and that there were lots of things in the Piranesi that I did not want at all.’ He remembered that this process of selection and refinement was particularly difficult because of the extent to which the Piranesi image dominated his thoughts. So obsessed did he become with the making of T04910 that he brought the canvas from his studio in Stratford, east London, to his partner's home in Bow in order to be able to work on it without breaks. He cannot now recall exactly how long it took him to complete T04910, but said it was rare to finish such a work in less than a month. In conversation Allington said he could not remember the exact source for the title of T04910. ‘Seated in Darkness’ might relate to the throne and its shadow in the Piranesi print. The artist normally takes his titles ‘from somewhere in the real world’, and he suggested that it was simply a ‘phrase that got stuck in my head while I was working’.

The process of working on the Piranesi image had been a success in that it no longer perturbed him: in conversation he said, ‘I did not have to worry about the Piranesi any more. It allowed me to move on’. A subsequent work, however, was quite close in theme to T04910, and was also based on a Piranesi print. ‘Contents of Two Rooms’, 1987 (repr. Edward Allington, Diane Brown Gallery, New York 1987, p.18), was executed in the summer of 1987 in New York a few months after T04910. Allington did not have access to his books on Piranesi, but based the work on memories of sarcophagi that occur in a number of Piranesi etchings, notably in ‘View of a Tomb Outside the Porta del Popolo on the Ancient Via Cassia’ (repr. Piranesi: Archaeologist and Vedutista, exh. cat., Weinreb Architectural Gallery, vol.10, 1987, no.62). In one half of the diptych ‘Contents of Two Rooms’, the sarcophagus shape, with its brokenedged slab-like base, appears to be falling onto the floor; in the other half, the sarcophagus is upturned and broken, and the base has more or less disappeared. In conversation with the compiler on 22 June 1994 Allington explained that his interest in the slab-like base of the throne in the Piranesi could be seen, in developed form, in the base with the sarcophagus in ‘Contents of Two Rooms’ and also in the flat ‘island’ in the related work ‘An Island in Four Corners’, 1987 (repr. Tokyo exh. cat., 1988, no.30 in col.). More recently, Allington has drawn inspiration from another Piranesi print in a large work on paper in his collection, currently titled ‘After Piranesi’, 1988. The central element in the drawing was derived from a Piranesi etching, identified in the 1987 Weinreb Architectural Gallery catalogue as ‘Details of a filter system in the Castello dell'acqua Giulia’ (no.106, repr.).

In general terms, however, Allington feels that T04910 had marked a turning point in his work. In conversation with the compiler on 26 May 1994 he described T04901 as ‘rather lively and animated’, and added:

I felt that this is what this piece should be, but I was not sure that I liked it that much. Looking back at it now, I think there is no other way I could have done it. It feels absolutely right, but I look at it and find it rather disturbing. It is like too many secrets got out or something. I think it pulled me back into wanting to make the work much tighter.

Nothwithstanding the air of vitality of the architectural forms in T04910, Allington stressed that he was not interested in any psychological or anthropomorphic interpretation of the pieces: ‘All I work on is trying to get them to the point where I believe that they are absolutely correct at that point in time for me’. In the course of 1987 his sense of what was correct moved, at least in his sculptural work, towards straight-edged, quasi-industrial shapes. This is suggested in his use of standardised plinth-like forms in a works such as ‘Metropolitan Egypt from the East of London’, 1987, and by the pristine quality of the surfaces of an architectural piece such as ‘Unsupported Support’, 1987 (repr. New York exh.cat., 1987, pp.12, 15).

When asked on 22 June 1994 about the possible relationship between his work and the classical imagery in the work of the Italian artists de Chirico and Savinio, Allington acknowledged that there was an apparent similarity in subject and underlying concern with the theme of memory. However, he insisted that he had not been directly influenced by these artists and stressed that what was important to him in his classical imagery was its role as a vehicle for remembered experience rather than its link with Greco-Roman culture. Allington is passionately interested in Greek philosophy and classical architecture, but describes his work as being about ‘how memory fails’. What fascinates Allington is how difficult it is for us to know the reality of the past, and how treacherous or inadequate our memories and our sense of history can be. The throne-form in T04910, for example, is based upon the eighteenth-century print, but is transformed by his reworking of the original image. The print in turn is an idealised rendering of the antique throne which had been lost from view for centuries. The throne itself was undoubtedly inspired by earlier prototypes, and so on. In conversation Allington talked about how he had read that in classical times people looked to myths to account for the development of particular architectural forms: the acanthus leaves found in Corinthian order architecture, he said, were linked to a supposed earlier use of plants and trees as tombs. In a recent essay Allington quoted another related story taken from the same source: ‘In his book The Lost Meaning of Architecture [Cambridge, Mass., 1988] George Hersey recounts the famous Vitruvian story of the architect Callimachus, the tomb of the Corinthian girl, the basket of goblets held down by a tile and the acanthus leaves which had grown around it curling back against the tile. The tableau from which Callimachus created the Corinthian capital’ (‘It's in the Corners that you'll Find it’, in ‘Cell: Cella: Celda: Four Contemporary European Artists at the Henry Moore Institute’, exh.cat., The Henry Moore Institute, Leeds 1993, [pp.19–20]). Forms in art and architecture, he believes, are never neutral but embody meanings and concepts derived from their history. In an interview given in 1983 Allington spoke about his use of classical referents in his sculpture:

Most sculpture denies the past totally or recycles it into new products. So the past is considered as old junk that the artist recycles into new junk. Instead I try to reclaim the past for the present. Archaeologists waste time trying to reconstruct the past. They say, ‘In 504 BC this was going on ...’. By adopting this attitude they create a third kind of time: archaeological time as a product to be sold. My motive is quite different from this type of restoration. It's a way of making connections. I can't remember much about my childhood, for example, so I find through my dream diaries that something comes back to me. It doesn't matter whether that connection is true or not. And the same is the case with the idea of Greece. While reclaiming the past I am trying to accept that it never existed. And - whether or not it makes sense - in doing this I am reclaiming my own life.

(Interview with Stuart Morgan, in Edward Allington:

In Pursuit of Savage Luxury, exh. cat., Midland Group,

Nottingham 1984, p.27)

The white walls in drawings such as T04910 provide an essential context for Allington's classically inspired forms. In conversation Allington said that in 1979–80 he had decided to make his sculpture and large drawings specifically for the public spaces of galleries and museums, and used white walls and repeated modular spaces to provide a museum-within-a-museum setting for the invented objects. In the recent essay cited above, Allington wrote about the ‘taxis’ or framework of classical architecture, borrowing the term from The Poetics of Order, Cambridge, Mass. and London 1986, by Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre (‘Taxis divides a building into parts and fits into the resulting partitions the architectural elements, producing a coherent work. In other words, it constrains the placing of architectural elements that populate a building by establishing successions of logically organized division of space’, quoted in Allington 1993, [p.19]). In T04910 the white walls provide a framework of an ordered and logical space for the objects invented by the artist. In 1987 Joshua Decter, an American critic, saw Allington's use of museum-like spaces as setting up a dialectic with the expressive, sometimes anarchic, forms they contain:

Within Allington's practice, a ... dialectic exists in reference to the contradictory impulses of containment or ‘management’ on the one hand, and ‘expression’ or ‘manipulation’ on the other. In this way, Allington attempts to liberate the viewer from the ‘empirical’ object, by calling attention to the ‘constitution’ of the ideological/creative artifact in relation to other objects within the trajectory of History. Allington inscribes this dialectical tension through stylistic devices and idiomatic signs, such as the ‘sign’ of institutionalisation expressed by the introduction of rigid containment structures - surrogate display cases. Similarly, the use of highly controlled colours and tonal reductions makes reference to the tactics of museological ‘distillations’ of historical context. The carefully controlled monochrome becomes the index of the ‘invisibility’ of ideological (en)coding.

(Joshua Decter, ‘Edward Allington:

Allegorical Inventories, Artifactual Narratives’, in New York

exh.cat., 1987, p.8)

An aspect of the dialectical relationship between the different elements in T04910 is the disjuncture between the forms and their shadows. The critic Stuart Morgan has noted that in Allington's drawings ‘objects cast shadows so odd - either perverting the objects we assume have cast them or appearing out of perspective - that a dialectic is established between the “real” and its double which calls both into question’ (‘Edward Allington: Getting it Wrong’, in Edward Allington: New Sculpture, exh. cat., Riverside Studios 1985, [pp.3–4]). In T04910 the shadow that extends through the doorway on the right appears totally unrelated to the forms of the throne, while the shape of other shadows suggest the existence of more than one light source.

The artist had planned for some time to have a drawing show at the Marlene Eleni Gallery, and, though not executed specifically for the exhibition, T04910 became the centrepiece of the display, having been completed a month or so before the opening in April 1987. In addition, the exhibition contained the six preliminary drawings, a small number of ledgers and a book of wallpaper samples, embellished by the artist. The critic Mary Rose Beaumont (1987, p.234) reviewed the exhibition, beginning, ‘The minute space of this elegant first floor gallery seems to have been magically transformed by the faultless hanging of Edward Allington's new drawings’. Referring to ‘Seated in Darkness’, she wrote (ibid., p.235): ‘Classical shapes of fragments of fallen buildings float in a box-like space which displays the inherently illogical perspective of a de Chirico. The literal layers of the material are underpinned by the element of time so that it becomes in one sense a “remembrance of things past”, and yet in another a blueprint for an unrealisable dream.’

Allington does not frame his large works on paper, and would prefer T04910 to remain unglazed for as long as is consistent with its proper conservation.

The artist has approved this entry.

Published in:

Tate Gallery: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions 1986-88, London 1996

Explore

- architecture(30,960)

-

- features(8,872)

-

- architectural fragments(37)

- capital(102)

- corbel(33)

- periods and styles(5,198)

-

- classical(1,040)

- ruins(3,711)

-

- building(452)

- universal concepts(6,387)

-

- history(1,983)

- domestic(1,795)

You might like

-

Edward Allington Ideal Standard Forms

1981 -

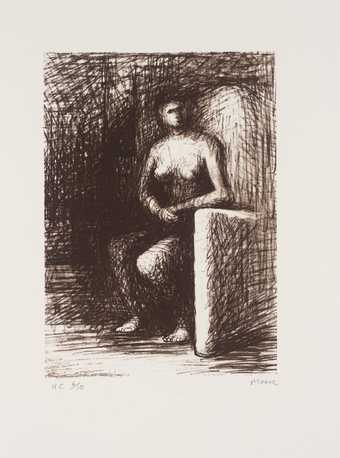

Henry Moore OM, CH Seated Figure III Dark Room

1974 -

David Hockney Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy

1970–1 -

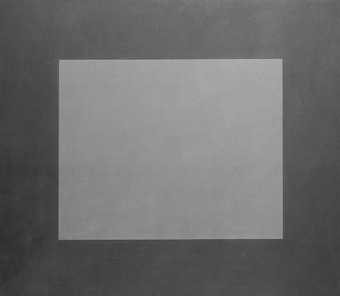

Peter Joseph No. 55 Green with Dark Blue Surround

1981 -

Art & Language (Michael Baldwin, born 1945; Mel Ramsden, born 1944) Index: The Studio at 3 Wesley Place, in the Dark (IV), and Illuminated by an Explosion nearby (VI)

1982 -

Sir William Coldstream Orange Tree I

1974–5 -

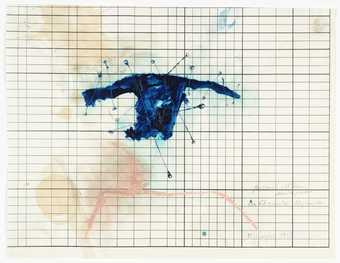

Martin Naylor Study for ‘Discarded Sweater’

1973 -

Peter Blake Portrait of David Hockney in a Hollywood Spanish Interior

1965 -

Basil Beattie Untitled Drawing

2000 -

Alison Wilding OBE Elephant 3

2003 -

John Virtue Landscape No. 109

1990–91