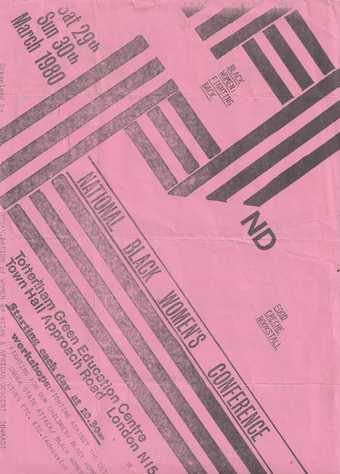

Fig.1

Poster for National Black Women’s Conference, March 1980, organised by the Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent (OWAAD)

Courtesy Janice Cheddie

Anjalie Dalal-Clayton: To start, could you tell me a little bit about yourself, your research interests and what your work since the 1980s has involved?

Janice Cheddie: To understand the context, I would have to start in the 1970s. I came into the cultural field not via academia or art school, but largely via feminist politics at first, and then anti-racist politics (fig.1).

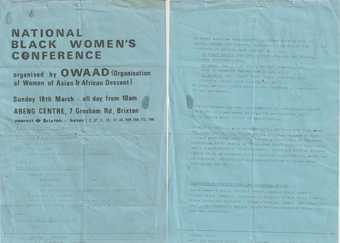

I grew up in London in the 1970s, after arriving with my family from the Caribbean in the mid-1960s. 1970s London, like many parts of the UK, was subject to frequent racist attacks on individuals of Black and Brown heritage. Organisations that hosted activities for Black and Brown communities were also subject to attack. I reached my teens in London in the 1970s, and in this space was a very rich creative and cultural ecology. Many cultural organisations were constructed as both formal collectives – including housing co-operatives, film collectives, workers co-operations, theatre collectives – and informal collectives, such as the English Collective of Prostitutes, Shocking Pink, Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent (OWAAD) and others (fig.2). These organisations were based on principles of coalition-building and constructing solidarities across race, class and sexuality. It is out of this coalition-building that the concept of political Blackness emerges. Therefore, in my early teens I was exposed to working in loose collectivising organisations with people that had differing approaches and methodologies to working toward a notion of feminism, anti-racism etc.

These organisations had within them some stated, and at other times implicit commitments to notions of cultural democracy, and to democratising the spaces where art was created, seen and owned, and who art was created by. As a young Black working class woman this approach was liberating and informed my future experiences of art as the site of possibility for participation, aesthetic experimentation and visual pleasure. Growing up in a working class Caribbean family, I did not visit museums and art galleries. The first art galleries I encountered were the small collective spaces of London Film Makers Co-op, Cockpit Arts, Four Corners, the Africa Centre, the Albany Centre in Deptford. It was at the Africa Centre that I first saw the BLK Art Group show.

Fig.2

Programme for National Black Women’s Conference, March 1979, organised by the Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent (OWAAD)

Courtesy Janice Cheddie

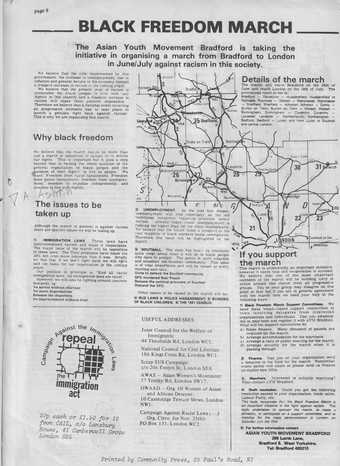

Fig.3

Details of Black Freedom March, June/July 1980, taken from Campaign Against Immigration Laws (CAIL) newspaper, Spring 1980

Courtesy Janice Cheddie

My experience in the informal organisations spoke of an equalitarian philosophy evidenced in non-hierarchical forms of organising and decision-making, skill-sharing and a Do-It-Yourself attitude (fig.3). Whether this be filmmaking, making magazines or establishing art organisations. These organisations and ways of organising were the very antithesis of the market driven, elitist and privately owned artistic sphere, which emerged during the Young British Art movement in the late 1980s.

Geographically, these community-engaged art and cultural organisations were often based away from the West End galleries in central London. These cultural organisations, which I first encountered and later worked for, allowed people to self-define as artists, rather than to be validated by a small and select number of galleries. These organisations existed outside the sphere of many large mainstream galleries, both publicly and privately owned.

Fig.4

Janice Cheddie’s passenger document for travel between Barbados and Grenada, July 1983

Courtesy Janice Cheddie

In 1983 I spent approximately two months travelling in the Caribbean visiting family with a friend. I travelled to Barbados, St Lucia, Jamaica and Grenada (fig.4). While in Grenada – which was under the leadership of Maurice Bishop and the socialist New Jewel Movement (1979–1983) – I spent some time in a youth camp.1 The youth camp explored different ideas around socialism, and there was some discussion about the role of culture within its development, much of which chimed with debates I had encountered in London. Shortly after this – I think it was through a community organisation that was attempting to establish a community cable station in the London Borough of Hackney in east London – I met the filmmaker Claudine Boothe. My interest in Boothe’s project led me to artist and producer Lina Gopaul, who was a member of the Black Audio Film Collective. It was through Lina Gopaul that I met other politically Black artists working in London and outside London. These artists and filmmakers were organising and working on issues that I had been involved in since my teenage years. I began to work with Black Audio Film Collective in 1985 and this experience was instrumental in my application to study cultural studies at undergraduate level at Goldsmiths College, University of London. I worked on the films Handsworth Songs 1986 and Who Needs a Heart 1991.

In the 1970s and early 1980s there existed a creative and cultural ecology that was challenging ways of thinking and making art, film and culture. Reflecting on my journey into cultural production, I would locate Black Audio Film Collective within this wider ecology. It was only post-Goldsmiths that I would have articulated a research interest in what is now known as the British Black Arts movement. From the inside, to me at the time, it really just looked like people around you were doing interesting things to challenge the idea of what an artist was and could be, addressing issues of race, aesthetics, access, cultural democracy and identity.

Anjalie Dalal-Clayton: Shaheen Merali has outlined the purpose, formation and contents of the Panchayat Collection through interviews and in his own writing, but I wonder if you could tell me in your own words, and from your own perspective, how you understand the collection as having come about and what its purpose has been over the past thirty years?

Janice Cheddie: The Panchayat Collection addresses the interdependent relationships of cultural conditions, predominantly documenting Stuart Hall’s ‘critical decade’ of the 1980s. It’s a witness to artists embracing the new technologies of video, copy art and digital media to explore through a range of aesthetic devices the political and social formation of identities, imagination and artistic production, the policing of sexuality, and the emerging migration and refugee crises of the early 1990s.

When I finished my undergraduate degree in the early 1990s the cultural landscape was very different and there was a general antipathy to creative work that addressed issues of subjectivity, difference and modes of viewing from outside the Euro-centric gaze. When I entered academia in the 1990s, Black art was often dismissed by liberal academics and younger curators as ‘just identity politics’ and without any artistic or cultural merit. It was widely seen as old-fashioned and passé. Most of the people I encountered in the wider London art world and academia at the time were increasingly focused on the Young British Artists (YBAs) and their exhibitions. After the completion of my PhD, my first or second year of teaching in London art schools coincided with the opening of the Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1997. The knock-on effect was that many of the artists, curators and writers I knew were struggling to find work and opportunities. I would personally argue that the effects of the YBA movement on writing, organising or curating the work of Black and Asian artists, for me, were very apparent, and this impact was visceral.

As with all collections, Panchayat is fragmentary and reflective of the conditions of self-funded collecting. Panchayat shared its history with many Black, BAME, feminist and other radical art archives, which ‘remain dispersed across the private, public and statutory sectors and, with few exceptions, these holdings remain at a rudimentary stage of cataloguing’.2 I would further argue that the Panchayat Collection is part of a wider ecology of archiving and collecting issue-based artists of the time, including Brixton Artists Collective, Women’s Art Library, South Asian Literature and Arts Archive (SALIDAA), African and Asian Visual Artists Archive (AAVAA), and the African-Caribbean, Asian and African Art in Britain Archive at Chelsea, University of the Arts London.

However, from my experience of working with the Panchayat Collection, I would say that it is characteristic of its time. The Panchayat Collection did not have a formal collecting policy and I think this is present in the wide-ranging material within the collection. The material also reflects some of the interests and concerns of different individuals who worked with it. I would, however, maintain that at its core is a focus on Black and Asian artists working on issue-based art. There are very obvious gaps in the collection – the most glaring is the lack of focus on faith-based identities within the UK communities of colour. However, as the social issues are fluid and changing, there is material within the collection on the emerging refugee crisis of the 1990s that would not have been a focus in 1988.

Anjalie Dalal-Clayton: Could you tell me about how you came to be involved in the Panchayat Collection and what your involvement entailed?

Janice Cheddie: I had known of Shaheen Merali since my A Levels. We both grew up in north London and attended the same further education college at the same time. I was studying for my A Levels and Shaheen was in the art department completing his art foundation. After A Levels we lost contact. Shaheen went to university and I worked or volunteered in a series of cultural organisations in London. Our paths crossed again when I started working with Black Audio Film Collective. In the late 1980s I was more aware of Allen de Souza’s writings in Bazaar: South Asian Arts Magazine and other publications in the 1980s and 1990s than I was of Shaheen. The next significant interaction that I was aware of was Panchayat’s involvement in taking the work of Black British artists to the Havana Biennial in 1989. I personally knew a number of the artists whose work went to Cuba. This was a big event. At the time there were very few biennials, with Venice being the major example. Through these connections, I became aware of Panchayat’s role leading up to the work going to Havana in 1989. The artist Symrath Patti, former Panchayat member, also organised for work of Black and Asian artists to travel to Cuba in 1991. The curation of the work of Black and Asian artists at the Havana Biennial related to the broad umbrella of Black Arts.

Panchayat members Shaheen Merali, Allen de Souza, Symrath Patti, Bhajan Hunjan and Said Adrus were all very much part of the Black art scene in the 1980s. 1989 also marked the opening of The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain, curated by Rasheed Araeen at the Haywood Gallery.

By the early 1990s I had met Shaheen individually and had been into the Panchayat office in east London a number of times. Shaheen had over the years requested that I give him some copies of my written work. Shaheen was interested in showing me the collection – I think this would have been at the end of the period that Allan de Souza was in the UK and working with Panchayat. At that time the main person working with Shaheen would have been Camille Dorney, a white Irish woman. The other founder members were largely absent during this time. This would have been at the same time I had started volunteering with the Women’s Art Library magazine in the mid-1990s. My first writing in Women’s Art Magazine was about Chila Kumari Singh Burman, in 1992. I started writing regular reviews for the new editor of the Women’s Art Magazine, Heidi Reitmaier, shortly after submitting my PhD in the mid-1990s. I think it was around this point that Shaheen started having conversations with me about working on some of the exhibitions that he was working on.

In 1997 I curated an exhibition with Keith Piper and Derek Richards at the Photographers Gallery called Translocations.3 This was a politically Black Arts exhibition. Also, when I was shown the Panchayat Collection, it included many Black artists, evidenced by Lubaina Himid’s 1984 Masters thesis from the Royal College of Art, which is held within the collection, and the conferences, ephemera and other material.

What interested me about the Panchayat Collection was that, unlike the African and Asian Visual Artists Archive (AAVAA), which at the time was relocating from Bristol to London, Panchayat had a more international reach. The collection included a lot of material from Canada – including First Nations work – and a wider focus on Asia, not just the Indian subcontinent. Shaheen was very much talking about the concept of a ‘Global South’ and broader ideas of solidarity that included material on class inequality, disability and sexuality, but a high proportion of the artists represented in the artist files within the Panchayat Collection continued to be what can be identified as Black or Asian artists. When I started attending meetings to discuss the work of the Panchayat Collection (this would have been approximately 1995–6), many of the meetings were spent discussing what the collection held and trying to redefine it away from ethnic categorisations to recognise the international work within the collection and also the focus on what could be called a ‘coalition’ of interests around the wider concept of issue-based work, which crossed race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality and disability.

The Panchayat committee when I joined at that time included Shaheen Merali, the photographer Robert Taylor, academic Helen Oxford Coxall, artist and archivist Rita Keegan, and video artist Sarbjit Samra. By 1996 it was clear that many of the artists that worked under the broad church of the British Black Arts movement had shifted away from that label and there were differing responses to that. At the time each of the Panchayat members brought a new emphasis and focus to the collection. I was positioned within the collective as working across academia and cultural production and had a history of working both within independent filmmaking, artist film and curating. Helen called herself a museum language consultant and she bought with her expertise on issues of museum language, exhibition design and display and formal arts education. Sarbjit was a member of the younger generation of artists who had graduated in the 1990s whose work was based in performance. Sarbjit, as far as I remember, would not have described himself as a Black artist. Robert Taylor was a photographer and his main focus was on issues of policed sexualities – this was the time of Section 28 in the UK and the AIDS crisis. Rita Keegan bought a wealth of expertise regarding archives and collections in the UK, fundraising, curating and feminist practice.

The Panchayat office in east London also included studio spaces and before the relocation to the University of Westminster, Permindar Kaur, Rita Keegan and Keith Piper had studios in the space. I moved Rita Keegan’s studio contents from Panchayat’s independent base into her home, and to my knowledge she has not had a formal studio since that time. This was symptomatic of a change in the radical infrastructure of London, I would argue. In the 1970s there were lots of cheap studios, housing co-ops and facilities that supported artistic production but by the early 1990s these places and supporting structures were rapidly disappearing, impacted by the growing gentrification of east London. This change in the socio-economic and cultural landscape created a perfect storm for many Black and Asian artists working in London – shrinking opportunities, the dominance of the Young British Artists phenomenon, the closure of small locally publicly funded art galleries and art education initiatives, and rising living and studio costs.

Anjalie Dalal-Clayton: In your essay ‘Justice and the Archive’, you describe the Panchayat Collection as an informal archive, making reference to Okwui Enwezor’s distinction between formal and informal collectives. Could you elaborate on this idea of the informal archive and the significance it has for understanding the Panchayat Collection?

Janice Cheddie:

Most of my work with Panchayat has been unpaid, voluntary and organised through collective decision-making. Ideas and decisions were made collectively and agreed around a broad principle of collecting, developing and contributing to the understanding and multiplicities of practices of primarily Black and Asian artists in Britain and artists working in the Global South. But the informal nature of the collection and its collecting strategy has meant that within the artists’ files there are a broad range of artists working on issue-based work and also mainstream British artists. The conference and campaigning material is largely drawn from the anti-racist, feminist and LGBTQ+ campaigns of the 1980s and 1990s and it reflects the growing debates around post-colonial scholarship and its intersection with cultural production.

I would argue that even though Panchayat has identifiable founders, the organisation of Panchayat, in my encounters, was that it had a fluid membership and that there was not a fixed idea of how the collection worked or, importantly, what was collected. This formation also marked out the Race Today collective, which is associated largely with the activist Darcus Howe, but had at one time sixteen members.4 It is in this sense, I assert, that Panchayat had a wide variety of people working as part of the collective between 1988 and 1997, when it moved into the library of the University of Westminster. Each of these people contributed to its development. This changing membership I would argue means that the meaning of the Panchayat Collection should be read as fluid, changing and open. Drawing on Enwezor, I would argue that it is the process of coalition building that forms the basis of organising, and reflects the basis of the democratic impulse enshrined in the concept of a ‘Panchayat’. By the time the collection transferred to the University of Westminster, Shaheen and I had informally agreed that we were both responsible for ensuring that the collection survived.

An informal collection is engaged with the principles of equal access and forms of democracy, based around collective action and coalition drawn from feminism and other forms of campaigning against inequality. What happens, then, when an informal collection transfers to a formal institution? What is the endpoint within these informal collectives? Is the endpoint a commitment to a minority of artists, curators etc. becoming uplifted and brought into the unequal systems of the institution? Diversifying the 1% of artists and curators (or top 5%) through their presence in major collections, while the structures of exclusionary education and consumption of culture remain fixed for an elite? Even if that elite is diversified? Within this diversification of the elite is the assumption that the majority of curators and artists are outside of that system. Built-in inequality for those with unequal access to financial, social and cultural capital that is the precursor to participation within an art system driven by market forces. If this was or is the desired endpoint, it does not need people like me to contribute unpaid intellectual, physical and emotional labour borne from informal organising to collect, preserve and disseminate this material. This can and should be done by financially and culturally enfranchised institutions and commercial entities. Following this through, there is an argument for collections like Panchayat to become monetised, or positioned as sites of extraction for a privileged few.

What if, however, the endpoint was an inherent understanding, as materialised within a non-hierarchical organising system, that there was a need to democratise the unequal art system and deliver a democratic art system based on access to culture as a human right? An understanding of the democratic principles and non-hierarchical forms or organising that informed and framed the coalition-building of the issue-based material becomes part of the process of understanding the collection itself. Striving for a more democratic art world is part of a process that will always be a Derridean ‘work in progress’ and re-imagined anew by each generation. A process that is always incomplete and never fully arrived at. In this context, my contribution to supporting, preserving and disseminating the work of the artists within Panchayat makes sense. Without this, I become just a random volunteer with time on my hands. It is in this sense that I argue that embedded within Panchayat is a democratic impulse. The collection and the artist’s work and wider contextual material and its democratic imperative are fused together. Thus I concur with artist Rasheed Araeen’s assertion:

These issues are not necessarily only about the predicament of the ‘other’ artists within a globalised western culture, or non-white artists in western societies, but they are much to do with the nature of dominant discourses and its institutional structures. These recognise and privilege certain artists and ignore others on the basis of a perception which is predetermined by legacies of the colonial past, and although benevolent, they are unable to examine their own premises and limitations.5

Anjalie Dalal-Clayton: The timeframe of the Panchayat Collection’s development coincides with profound changes in the arts, especially the emergence of ‘new internationalism’ and globalising perspectives. How do you feel this was reflected in archival practice and in the way art institutions were operating at the time?

Janice Cheddie: Reflecting on where we are now, I do not think ‘new internationalism’ had a profound impact. This can be witnessed in the movement of the Institute of International Visual Arts (InIVA) from being the predominant curatorial, publishing and exhibition-making entity in the 1990s, seeking to position artists of colour in mainstream art discourses, to its current role centred around the Stuart Hall Library and educational interventions and exhibition-making within the space of the library. It is in this sense, I would argue, that InIVA is following rather than driving the re-emergence of decolonisation debates concerning the arts and archives.

I would actually argue that the most potent effect was the rise of the Young British Artists movement. In the late 1980s there was a wide and diverse creative ecology of Black and Asian artists working in the UK, but during the 1990s this was radically reduced. It is interesting to note that the radical collective Race Today also ceased to function in 1988. Those artists that were able to maintain a consistent practice were predominantly those who had extensive networks within education and particularly higher education institutions, and from this base maintained a creative practice. This allowed them to take up different opportunities including opportunities to work internationally. Largely for those artists outside these formal structures this was not possible. I was fortunate to be able to secure funding for my PhD at that moment.

There continues to be a fraught relationship between the informal structures of collecting, represented by Panchayat and the Women’s Art Library, and the practices of cataloguing these collections within institutions. The professional practice of archiving and information management is very conservative and procedural, and it is only recently that these structures and procedures have been open to question. Archival and library classification systems too often seek clearly defined categories. If you are dealing with artistic practices and social identities that are evolving, this becomes problematic. Library and archiving practices too often slot items that fall outside its standard descriptions into a broad category, or do not catalogue them at all, or just describe them under a blanket term. This has been a continuous issue, whether you are looking at women’s history, working class history or the history of colonised peoples or communities of colour in the UK. Panchayat is an informal collection, like the Women’s Art Library and others. They stood outside these structures, and the process of transferring these collections into formal collecting institutions has been the subject of negotiation. From my involvement with the Mayor’s Commission on African and Asian Heritage in London, there have been debates about how catalogue records have not recorded histories of communities of colour, and have used stereotypical language.6 There is an ongoing conversation within the archival, museological and information management professions about this. Too often, from my experience, this work is left to individual, sympathetic archivists and librarians, who quickly get burnt out, when in reality this work should not be left to individuals. The issue of inclusive terminology needs to be addressed at the level of professional standards. How to represent the historical terminology of ‘political Blackness’ that forms the Panchayat Collection and the Black Arts Movement within cataloguing and archival description practices continues to be the subject of discussions.

Anjalie Dalal-Clayton: What did the Panchayat Collection enable those involved with it, and those represented in it, to do?

Janice Cheddie: I met art historian Mora Beauchamp-Byrd in the early 1990s when she was conducting research for her exhibition Transforming the Crown, and I know that she had visited Panchayat and met with Shaheen as part of her research.7 Shaheen was also in contact with members of the Toronto-based culture magazine FUSE and I met a number of writers and curators that were writing for FUSE through Shaheen. These meetings were sometimes at the Panchayat offices and sometimes elsewhere. The artist Paul Eachus used the collection to research and curate his work on masculinities.8 Artist Symrath Patti used the collection to research the Havana Biennial 1991 contingent of British Black artists. The collection would have been used by the curators Sally Tallant and Sharmini Pereira when they worked on the Slow Release exhibition at Bishopsgate Goodsyard in 1999. Shaheen was very friendly with the artist and curator Shezad Dawood and I met him a number of times at the Panchayat offices and I am sure he would have used the collection and was aware of its contents. There are lots of dissertations of different levels within the collection, which also demonstrates how it was used for formal academic research. Shaheen had a close relationship with Lois Keegan, former director of the Live Arts Development Agency (LADA), and there were lots of conversations between the two collections about funding and development. The other person who would have used the collection was curator and gallerist Niru Ratnam when he was an academic. In her book Recordings: A Select Bibliography of Contemporary African, Afro-Caribbean and Asian British Art (1996) the curator Melanie Keen explicitly acknowledges Shaheen Merali and therefore would have visited the collection. We also worked with the Arab-Jewish photographer Anna Sherbany on her exhibition Story Time: An Exhibition by Artists Living in Israel/Palastine, involving collaborations between Jewish and Palestinian artists living in Israel.9 The strategies and interventions of artists from the Black Arts movement informed some of Sherbany’s thinking during the development of this exhibition and for the catalogue.10

Anjalie Dalal-Clayton: Before the relocation of the Panchayat Collection to the University of Westminster Library, where was it stored, how could it be accessed, who used it, and how did they use it?

Janice Cheddie: Panchayat Arts Education Resource Unit was based in a warehouse in east London that consisted of artist studios and an office. The collection was stored in the office within a series of filing cabinets, shelves and box files. Access to the collection was usually via appointment. However, the studios were open and if you were in the office, people would access the office. It was often an informal arrangement.

Panchayat did not engage in a formal process of archiving, but rather preserved, collected and gathered largely open-source material in an informal way. This did not change during its time as an independent entity. I think it is important to state that the collection was a resource that was actively used throughout its independent operation by artists, curators, independent scholars, and by members of Panchayat to curate, research and reflect upon. In this sense, moving into the formalised setting of a university library disrupted these dynamic, fluid and fragmentary operations.

Throughout Panchayat Collection’s time at the University of Westminster, Shaheen and I were in close and regular contact. During this time, we both felt a keen sense of responsibility for the Panchayat Collection. It was against this backdrop that Shaheen Merali contacted me in late 2014 to tell me that the University of Westminster wanted the Panchayat Collection moved out of the library facilities. The library staff at the University of Westminster Library also informed Shaheen and I that Tate librarian Maxine Miller had visited the Panchayat Collection and had expressed an interest in relocating it to the Tate Library. Shaheen and I were presented with two options: either to move the collection into Shaheen’s garage space, thus providing limited free access to the collection, or to discuss with the Tate Library the possibility of moving the collection into its Special Collections, offering the possibility of even greater access to, and hopefully research on, the collection.

In early 2015, when Shaheen arrived at the University of Westminster Library, the artist files, slides and ephemera were stored in a locked side room and if I remember correctly this room was not labelled. So any visitors, researchers or students had to know that the collection was even held there. The books, slides and videos were dispersed within the main university library collection, but were not immediately identifiable as part of a specific collection.

After several weeks of discussion, where we weighed up the options in relation to our own capacities and lack of funding, Shaheen and I jointly agreed to transfer the collection to the Tate. During the period of discussion, we also met with Maxine Miller (a woman of African Caribbean descent) and she recognised the importance of the collection. I would personally state that Maxine Miller’s presence at the Tate Library was a very important factor in the decision to transfer the collection to Tate. Therefore, there are two women who have been very important in seeing the historical value of the collection and in securing its long-term future: Maxine Miller and Helen Oxford Coxall.

The difference between Panchayat’s form of cataloguing and that of the University of Westminster was most apparent when Shaheen Merali and I visited the collection at the University of Westminster in early 2015. During this period Shaheen and I spent a lot of time going through the artist files and ephemera, which one member of the library staff referred to ‘thin things’. Artist ephemera, the non-Dewey system of cataloguing artists without cross-referencing material, meant that the librarians did not know how to categorise the collection within their formalised academic system. This material, the ‘thin things’, were and are some of the only documents existing on public record of particular artists, and are really important in documenting the continuing practice of artists of colour. This material, I would argue, forms the most interesting part of the collection. It was very apparent, at that moment, how institutional categorising was at odds with the informal collecting of Panchayat.

Anjalie Dalal-Clayton: Could you tell me more about the role played by Dr Helen Oxford Coxall, especially in relation to the transfer of the Panchayat Collection to the University of Westminster Library?

Janice Cheddie: Without Helen being a permanent member of staff at the University of Westminster the Panchayat Collection would have ended up in Shaheen Merali’s garage, and given that he relocated to Europe for seven years, large sections of the collection would have been lost and/or in a poor state had it moved with him. Helen’s formal link to the University of Westminster was crucial in saving the collection for future researchers that has now entered the Tate Library. Without her vision and energy and institutional contacts the collection would not be at Tate.

Helen was important on a number of levels. Firstly, she was instrumental in highlighting how the collection could be integrated into the formal education of curators in a way that would now be described as part of the new museology that emerged in the 1990s. Helen’s research was on the interaction between the artwork and its reception and she was useful in getting Panchayat members to think about these relationships. It is in this sense that Helen was able to articulate the ability of the collection to have value within curriculum development at the University of Westminster, not just as a resource to identify individual artists, but in terms of its wider engagement with contextual issues of interpretation and reception within the museological sphere. Secondly, Helen was key to the development of a proposal for an undergraduate degree that was to be based on the Panchayat Collection after its transfer to the University of Westminster. She was very clear about how the disparate elements of the collection could constitute a rigorous scholarly engagement with, and interaction between, artistic production, reception, interpretation and the development of an inclusive model of engagement with differing audiences. Unfortunately, the degree did not receive final approval but her understanding of the collection as a tool for education and academic research was important in widening the terms of engagement with the collection. It was a useful exercise that I have been able to use in other settings.

Helen was also a great champion in seeking to position Shaheen and I as tutors within the teaching staff. While Helen was not formally part of the curatorial team of the 1999 Panchayat exhibition Slow Release at Bishopsgate Goodsyard, she was one of the individuals that was consulted on the exhibition development. Furthermore, Helen was Panchayat’s champion within the University of Westminster. She understood the collection, and the importance of artist ephemera. With her guidance students would have been alerted to the value of the collection. Unfortunately, Helen began to face health challenges and died in 2009.11

Anjalie Dalal-Clayton: Finally, what are your hopes for the future of the Panchayat Collection? How would you like to see it being opened up and used over the coming years?

Janice Cheddie: During its time at the University of Westminster, the Panchayat Collection had fallen into the status of a largely unused resource. It is clear that the collection needed researchers, students and academic staff engaging with it as a resource for teaching, research and practice-based interventions. Without key individuals such as Helen Oxford Coxall, utilising the Panchayat Collection for teaching and research fell away, and it evidences the need for any collection to be embedded within the hosting institution’s research culture.

The Panchayat Collection was gifted to the Tate Library as a politically Black visual arts collection. This is why it has been so important for me to argue for the collection to be catalogued and to make sure the catalogue is accessible online. My personal hope is that with the transfer to the Tate, the material held within the Panchayat Collection will continue to be freely available to funded and independent researchers, scholars, artists and curators to generate new scholarship and creative interventions. It is important that the Panchayat Collection is not perceived to have a singular narrative, and that it is open to a diverse range of researchers and research approaches. However, this can only be achieved if the collection as a resource is embedded within the research and curatorial culture of the Tate as an independent research organisation, and that the Tate Library continues to facilitate a wide range of researchers.