Not on display

- Artist

- James Barnor born 1929

- Medium

- Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

- Dimensions

- Image: 282 × 284 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Gift Eric and Louise Franck London Collection 2013

- Reference

- P13419

Summary

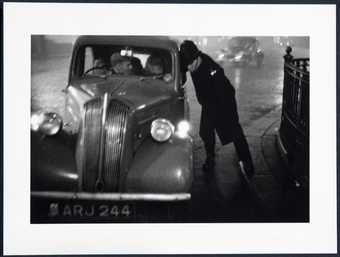

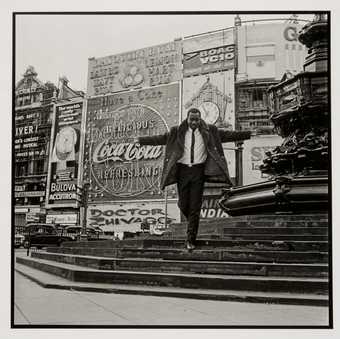

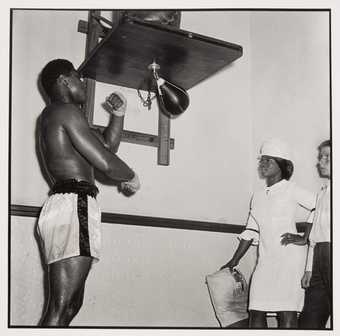

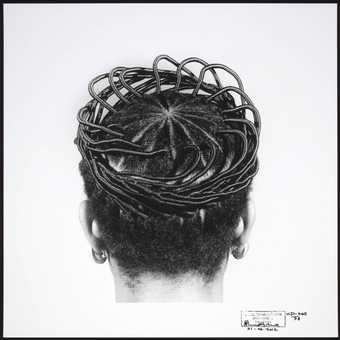

This is one of a group of black and white and colour photographs in Tate’s collection taken by James Barnor in the 1960s (Tate P13419–P13421, P13484, P14381–P14384). Barnor’s portraiture played a key role in documenting black women and men who, in the post-war period, had immigrated to Britain from African countries and were establishing their identity as British. His photographs include images of unnamed subjects, such the two smartly-dressed women in Wedding Guests, London 1960s who pose in front of one of the classic British telephone boxes designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, presumably on their way to a wedding. Other portraits feature public figures, such as the radio journalist Mike Eghan, host of a popular Ghanaian talk show aired on the BBC (Mike Eghan at BBC Studios, London 1967 and Mike Eghan at Piccadilly Circus, London 1967). One image documents the visit of American boxing legend Muhammad Ali to London in 1966, showing Ali training in advance of a fight (Muhammad Ali Training, Earl’s Court, London 1966). A number of shots feature portraits of ‘cover girls’ that were originally published as covers for the magazine Drum, a publication originally from South Africa (Drum Cover Girl Erlin Ibreck at Trafalgar Square, London 1966, Drum Cover Girl Erlin Ibreck, London 1966). In Drum Cover Girl Erlin Ibreck at Trafalgar Square, London the model poses at one of London’s most iconic sites; in Drum Cover Girl Erlin Ibreck, London she stands in a London street, leaning against a car. These photographs capture the mood and fashion of London’s ‘swinging Sixties’, as well as the aspiration of Black immigrants to integrate into British society.

Barnor moved to Britain from Jamestown, Ghana in 1959. He lived and worked in London for ten years, before returning to Ghana in 1969. Over this period his mainstay was his work for Drum, which had been an integral part of the South African resistance movement known as the Sophiatown Renaissance. The magazine had launched the career of a number of black photographers from South Africa and combined campaigning journalism with light-hearted photo stories. It spread as a franchise across the African continent, including editions in Kenya and Nigeria and its readership extended to the black community in London.

The art historian Kobena Mercer has commented on the importance of Barnor’s role in documenting the black diaspora in Britain:

Cutting across the divide between periphery and metropolis, Barnor’s images suggest that ‘Africa’ has never been a static entity, confined to the boundaries of geography, but has always has a diasporic dimension. The scattering of culture and identity away from one single origin into multiple sites of resistance was once seen as a tragic loss of ‘roots’, although Barnor’s oeuvre seems to tally more with contemporary post-colonial thinking that regards diaspora as the alter-national product of world-making journeys, which pass through numerous cross-cultural ‘roots’. As such it is not a minus but a plus.

(Mercer, in Autograph ABP 2010, n.p.)

The prints in Tate’s collection were made by the artist in 2010 and were previously in the Eric and Louise Franck Collection, London.

Further reading

Kobena Mercer, ‘People Get Ready, James Barnor’s Route Map of Afro-Modernity’, in Ever Young James Barnor, exhibition catalogue, Autograph ABP, London 2010.

James Barnor, James Barnor, Ever Young, Paris and London 2015.

Elena Crippa

April 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- photographic(4,673)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

- hair(437)

- head / face(2,497)

- black(796)

- Eva(1)

- individuals: female(1,698)

- UK London(1,640)

-

- London - non-specific(3,659)

- lifestyle and culture(10,247)

-

- fashion(157)

- contemporary society(640)

- multiculturism(7)

You might like

-

Sergio Larrain London

1959 -

Sergio Larrain London

1959 -

James Barnor Mike Eghan at Picadilly Circus, London

1967, printed 2010 -

James Barnor Muhammad Ali training, Earl’s Court, London

1966, printed 2010 -

Mario de Biasi London

1975 -

James Barnor Flamingo cover girl Sarah with friend, London

c.1965, printed 2010 -

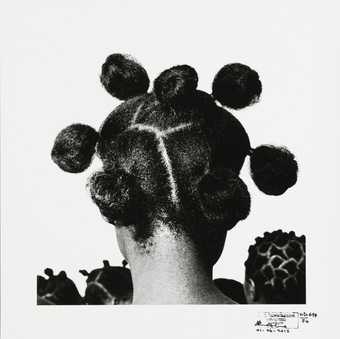

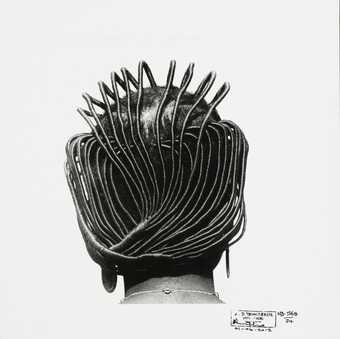

J.D. Okhai Ojeikere Untitled (Roundabout)

1974, printed 2012 -

J.D. Okhai Ojeikere Untitled (Suku Sinero/Kiko)

1974, printed 2012 -

J.D. Okhai Ojeikere Untitled (Onile Gogoro Or Akaba)

1975, printed 2012 -

J.D. Okhai Ojeikere Untitled (Star Koroba)

1971, printed 2012 -

J.D. Okhai Ojeikere Untitled (Mkpuk Eba)

1974, printed 2012 -

J.D. Okhai Ojeikere Untitled (Abebe)

1975, printed 2012 -

J.D. Okhai Ojeikere Untitled (Agaracha)

1974, printed 2012 -

Marc Riboud London

1954, later print -

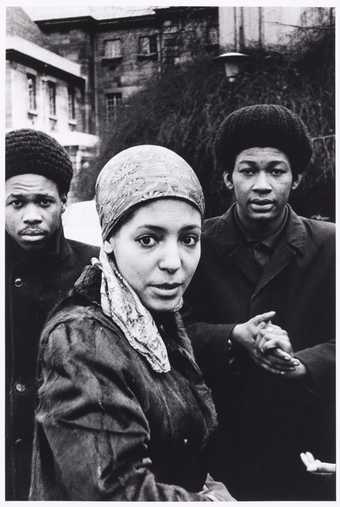

Neil Kenlock MBE Leila Hussain at a demonstration, London

1970, printed 2010