In Tate Britain

- Artist

- Wilhelmina Barns-Graham 1912–2004

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 514 × 609

frame: 674 × 777 × 74 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1964

- Reference

- T00708

Display caption

Barns-Graham lived in St Ives and her art combined natural subjects with the influence of older abstract artists Ben Nicholson and Naum Gabo. This is one of several works painted following a visit to the Grindelwald Glacier in Switzerland in 1948 where she had direct experience of the monumental shape of the glacier, its light, and the contrast between solidity and glass-like transparency. This led her to attempt to combine multiple views ‘from above, through and all round, as a bird flies, a total experience’.

Gallery label, September 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham born 1912

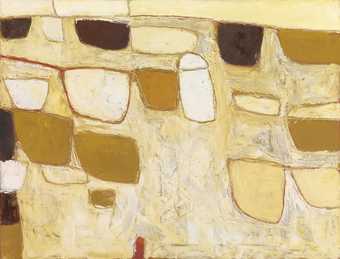

Glacier Crystal, Grindelwald

1950

T00708

Oil and graphite pencil on canvas 514 x 609 (20 1/4 x 24)

Inscribed in pencil ‘W. Barns Graham 1950’ bottom left

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1964

Provenance:

Purchased from the artist through the Redfern Gallery, London by Dr Harold Widdup 1952 and bequeathed to the Contemporary Art Society 1964

Exhibited:

Vieira da Silva, French Paintings, W. Barns-Graham, Jacques Villon, Redfern Gallery, London, January-February 1952 (103, as Crystal)

Forty Years of Modern Art 1945-85, Tate Gallery, London, February-April 1986 (no number)

W. Barns-Graham: Retrospective 1940-89, Newlyn Art Gallery, June-July 1989, Edinburgh City Art Centre, October-November, Perth Museum and Art Gallery, December 1989-January 1990, Crawford Centre for the Arts, St Andrews, January-February, Maclaurin Art Gallery, Ayr, May (17, reproduced p.23)

Literature:

Tate Gallery Report 1964-5, London 1966, p.30

Michael Tooby, Tate St Ives: An Illustrated Companion, London 1993, p.47, reproduced (colour)

Reproduced:

Tom Cross, Painting the Warmth of the Sun: St Ives Artists 1939-1975, Penzance and Guildford 1984, 2nd ed. 1995, p.72 (colour)

From 1949 to 1952 Wilhelmina Barns-Graham produced a series of paintings, drawings and prints derived from a 1948 trip to the Upper and Lower Glaciers at Grindelwald in Switzerland. That body of work has been seen as a pivotal moment in her artistic development, marking a new degree of abstraction, in keeping with contemporary art practice, which she would extend further during the 1950s. The critic J.P. Hodin believed that with the Glacier paintings she ‘reached not only a material beauty ... but also a musical beauty through abstract forms’.[1]

This is one of the earlier paintings of the group, which she said was not a ‘series’,[2]

and is typical in its combination of a relatively literal representation of landscape with more allusive forms.

Barns-Graham was invited by the Brotherton family, friends from St Ives, to drive with them to Switzerland in the summer of 1948. They visited Grindelwald and climbed to the top of the huge glaciers there with the use of ropes and pick-axes. The artist was powerfully moved by the experience of this extraordinary natural phenomenon and, while the family continued their holiday elsewhere in Switzerland, she remained, climbing it repeatedly. She wrote a lyrical account for the Tate Gallery in 1965:

At Grindelwald I was climbing on the two glaciers “Upper” and “Lower”. The massive strength and size of the glaciers, the fantastic shapes, the contrast of solidarity [sic] and transparency, the many reflected colours in strong light, the warmth of the sun melting and changing the forms, in a few days a thinness could become a hole, a hole a cut out shape losing a side, a piece could disintegrate and fall off, breaking the silence with a sharp crack and its echoes. It seemed to breathe! Enormous standing forms, polished like glass with sharp edges, its roofs by comparison hard snowy rounded and textured which could include buried in it and on it, huge and tiny stones and rubble ... Once while working against the evening light rapidly fading, I experienced a terrifying desire to roll myself down the mountain side. Calmly as I could I came down the wood steps cut in to the ice, Grindelwald far below ... I heard the awful roar of an avalanche and seeing what looked like a trickle of salt in the distant heights. All this and the many moods beautiful and frightening fascinated me.[3]

That she could recall her visit with a similar clarity and emotion in 1998, fifty years after the event, is testimony to the profundity of its effect on her.[4] She described the sheer ‘face’ of the glacier with large ‘cuts’ into it and the undulating top surface that was littered with fallen rocks and other rubble. She also remembered the different sensory experiences of the place. The top was a dirty white in colour, but from above appeared green, like glass,; she recalled it set against an ultramarine sky and these colours may be seen in Glacier Crystal. The heat of the sun melted patches of the surface, where pools of water formed, and caused parts of the glacier to move, emitting occasional loud cracks, and chunks of ice to fall off.

In her accounts Barns-Graham gave some idea of the relationship between the paintings and the original motif. She reported that she had made notes, drawings of a fairly literal kind in pencil, charcoal or ink and occasional quick gouaches on the spot or in her hotel room shortly afterwards. These then provided a basis for the subsequent paintings. In 1965, she explained that the ‘likeness to glass and transparency, combined with solid rough ridges made me wish to combine in a work all angles at once, from above, through, and all round, as a bird flies, a total experience’.[5]

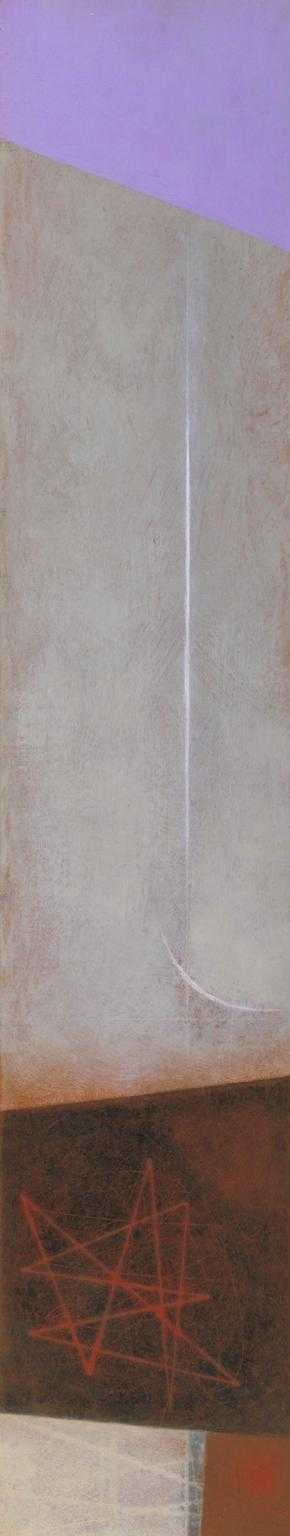

In 1998 she explained more specifically that the horizon line at the top of the painting represented the top of the glacier as if it was seen head-on, while the concentrated network of lines at the bottom was imaginative and intended to suggest cut-glass edges, splinters and the transparency of the ice. The crystalline appearance of this passage, which the title of the work points up, reflects the crystal patterns of the broken pieces of ice.[6]

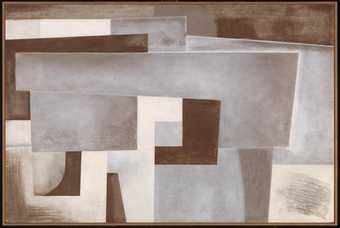

The technique employed by the artist contributes to the work’s signification. The design was drawn over an off-white oil ground in pencil and paint was applied in layers (up to four in places) that varied from thin washes to thick scumbling. These were scraped back in broad strokes with a blade and linearly with a point; though the paint is generally lean with added white, this abrasion has given it a sheen. Pencil lines were added over the paint and some of these were strengthened with finely brushed black. This technique was typical of many works made in St Ives in the late 1940s and early 1950s and derived from the example of Ben Nicholson. The ‘scratch and scrape’ practice was especially characteristic of the work of John Wells - seen in Painting

1957 (Tate Gallery T02234), for example - and Peter Lanyon, who in 1950-1 worked the first version of his Porthleven

(Tate Gallery N06151) so heavily that the canvas disintegrated. The scraping process produced a picture surface of varying texture and luminosity in which successive paint layers can be seen through each other. Its widespread adoption may be seen to reflect both the privileging of the hand-made among St Ives artists and their preference for surfaces and materials that relate to or echo natural objects and processes.

Thus Barns-Graham’s practice may be seen to parallel the subjects that interested her. In the late 1940s she told Hodin that she wished to develop a form of landscape painting that consisted of ‘a process of laying bare’ to suggest ‘the eeriness of age from within’.[7]

Consistent with that was her later description of her work of the early 1950s as ‘abstractions from corroded forms in Nature, affected by sun, wind, water, (sea and rain), clay country in Italy, rock and sand formations in Sicily, Cornwall and Spain’.[8]

The artist saw the Glacier paintings as the first step in the direction of paintings in which the means of their making can be said to mimic the natural processes which shaped their motifs. Hodin pointed up the parallel between the subject and the method employed in its painting: ‘“I like”, she writes, “nature in motion working on and changing itself: rocks, walls, moss, stones, pebbles, rust, granite surfaces, fungi, sea pools, branch barks”. This is also the method of her working.’[9]

Such natural themes predominated in British painting and sculpture after the war and were especially associated with St Ives artists. To some degree this may be seen as an extension of the neo-romantic revival of landscape during the 1940s which also encompassed such subjects as Graham Sutherland’s organic anthropomorphs. In St Ives, while Nicholson used landscape as a backdrop for late Cubist still-life compositions, younger artists like Barns-Graham developed a formal and theoretical revision of the subject. Her recollection of the glacier reveals the degree to which this was based on an abandonment of visual perception as the primary source in favour of ideas about one’s experience of a place and natural processes. This adjustment can be seen to have had both symbolic and formal implications for the objects produced.

Barns-Graham’s description reflects the way several St Ives artists sought to represent in paint the experience of being in a place, one’s spatial movement through it and its personal and cultural associations. The multiple view point which she wished to establish was, in particular, a key component of Lanyon’s attempts to formulate what was seen as a post-Cubist landscape. These ideas seem to have been informed by the theory of ‘duration’ of the French philosopher Henri Bergson, who had earlier influenced the Cubists, and were in accordance with the phenomenology of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, then very popular in artistic circles in France. More directly, it reflects artists’ desire to bring landscape up to date with contemporary artistic practice and to reintegrate an idea of Nature into art. The latter is reflected in Barns-Graham’s reference to bird flight, an image which recurs in St Ives’s artists’ writings as a natural example of the description of space which was a key to the constructions of Naum Gabo.

Though Gabo left Britain for America in 1946, he remained a seminal influence on younger artists in Cornwall. Barns-Graham recognised a common debt amongst her circle and attributed a shared crescent form in Glacier Crystal, Wells’s Sea Bird Form 1951 (Tate Gallery T02230) and Lanyon’s Headland

1948 (Tate Gallery T06466) to Gabo’s example. ‘Gabo’, she said, ‘has had a big influence, he probably opened my eyes to see the glaciers’.[10]

The translucent planes which make up Glacier Crystal can be associated with the paintings that he had produced in Carbis Bay and to the transparent curving forms of his constructions. Barns-Graham had bought a small version of one of these, Spiral Theme, during or shortly after the war (now in Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art; for another version see Tate Gallery T00190).[11]

Like several of his works, this might be said to consist of planes of perspex wrapped around a central form and such a sense of enwrapment may be discerned in the work of the younger artists too. One can see this aspect in Glacier Crystal, in which the angular lines of the ‘crystal’ are enfolded within curving planes of colour. Similar forms may be identified in the work of Lanyon, Wells and Hepworth from the late 1940s. Lanyon and Wells both produced abstract paintings of organic forms made up of spiralling and enfolding planes and lines. To such works Wells applied the name ‘Gaboids’,[12]

and the same term may as well be applied to the lower form in the glacier painting.

A theme of birth and regeneration underlies this body of works. Many of Lanyon’s pieces of the period were grouped together as the ‘Generation Series’; Wells entitled one of his ‘Gaboids’ Embryonic

1947 (private collection)[13]

and Hepworth, too, associated her oval sculptures with ideas of birth and gestation. This latter instance has been linked to the influence of Adrian Stokes’s absorption in psychoanalysis and, specifically, to the theories of Melanie Klein.[14]

Such a theme is likely to lie behind the recurrence of the motif of crystals in the work of these artists. As natural entities which display geometric form and organic growth, crystals were ideal for their brand of naturalised Constructivism. In this way, Barns-Graham’s painting can be seen as part of the revision of constructive art after the war in response to a reaction to the austerity of pure abstraction and the perceived need to reconnect with natural roots.

Organicism, in a variety of forms, would become a dominant theme in British artistic theory and practice during the 1950s. This was based, in large part, on the writings of Herbert Read and was often focussed on the Institute of Contemporary Arts, of which he was the president. The inclusion of Barns-Graham’s Glacier (Blue Cave) 1950 in the opening exhibition at the ICA’s Dover Street premises may, thus, be seen as an indication of the historical relevance of the series.[15]

Installation photographs reveal that a small glacier painting was included in the exhibition Abstract Paintings, Sculptures, Mobiles organised by Adrian Heath at the Artists International Association (AIA) in 1951.[16]

Later, the artist’s association with Leeds School of Art - where the pedagogic regime known as ‘Basic Form’ or, alternatively, ‘The Developing Process’ was based on organic principles - would link her to another group of artists that included Victor Pasmore and Harry Thubron. That Barns-Graham’s abstract landscapes associated her with the group that became known as Constructionists as much as with St Ives is reflected by the fact that Glacier Crystal hung alongside Pasmore’s Square Motif in Red, Blue, Green and Orange, 1949-50 in the collection of Harold Widdup.[17]

Barns-Graham had been aware of some of the theory behind their organic development of form early on, as she had met Professor d’Arcy Wentworth Thompson, whose On Growth and Form was a key text, in St Andrews before the war.[18]

His proposition that natural shapes were determined by growth ran parallel to the interest in the natural shaping of forms which she and other artists sought to mimic.

In 1965 Barns-Graham included this work in a list of twenty-three glacier paintings, thirteen of which dated from 1950, six from 1951 and two from 1952; two were undated. She described Glacier Crystal as one of the earlier works, and explained that ‘the later paintings were more “abstracted”, more intersecting lines as such, colour not used as literally, sky as brown, ice as pink’.[19]

The works were on canvas, hardboard and wood and ranged in size from Suspended Ice 1951 (private collection) at 46 x 36 inches to Glacier Pale Green 1950 (private collection), which is 10 x 14 inches. Several of the group seem to relate closely to the Tate’s painting. Glacier Grindelwald Tiger 1950 (Arts Council Collection),[20]

Upper Glacier 1950 (British Council)[21]

and Glacier (Blue Cave) 1950 (private collection)[22]

all have similar skylines, with a curving form that sweeps around the right hand side of the composition to form a peak near the middle of the horizon. Each has a more concentrated area at the bottom similar to the ‘crystal’ in the Tate work. Twenty one of the paintings, all from 1950 or 1951, were shown in Barns-Graham’s exhibition at the Redfern Gallery in 1952, where the exhibits were divided into ‘glaciers’, ‘landscape paintings’, ‘other paintings’ and drawings. The catalogue shows that several of the works had already been sold, including the Arts Council’s Glacier Grindelwald Tiger and the British Council’s Upper Glacier, though some were borrowed back for the occasion. Barns-Graham had held an exhibition of glacier drawings at Downing’s Bookshop in St Ives, a regular exhibiting space for modern-minded artists, in 1950 which, she told the Tate Gallery, had ‘attracted the attention of Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth and their encouragement’.[23]

The previous November, she had contributed two Glacier off-set monotypes to an exhibition of Prints, Drawings and Watercolours at the Penwith Society in St Ives.

Chris Stephens

November 1998

[2] Interview with the author, 5 May 1998

[8] Typescript sent to the Tate Gallery, 2 February 1965

[9] Hodin 1950, p.122

[11] Christina Lodder and Colin C. Sanderson, ‘Catalogue Raisonné of the Constructions and Sculptures of Naum Gabo’, in Steven A. Nash and Jörn Merkert (eds.), Naum Gabo: Sixty Years of Constructivism, Dallas 1986, p.233, no.52.6

[12] John Wells, interview with the author, 30 December 1995

[14] Matthew Gale and Chris Stephens, Barbara Hepworth: Works in the Tate Gallery Collection and the Barbara Hepworth Museum St Ives, London 1999

[16] Installation photograph reproduced Alastair Grieve, ‘Towards an art of environment: exhibitions and publications by a group of avant-garde abstract artists in London c.1951-5’, Burlington Magazine, vol.132, no.1052, November 1990, p.775, fig.14

[17] Probably the same work as Abstract in Indian Red, Crimson, Blue, Yellow, Green, Pink and Orange, 1949-50, reproduced in Alan Bowness and Luigi Lambertini, Victor Pasmore: with a catalogue raisonné of the paintings, constructioons and graphics 1926-79, London & Milan 1980, p.95 (colour)

[18] d’Arcy Wentworth Thompson, On Growth and Form, Cambridge 1917, 2nd. ed. 1942

[20] Reproduced in W. Barns-Graham: Retrospective 1940-89, exhibition catalogue, City of Edinburgh Museums and Art Galleries, 1989, p.24

[21] Reproduced ibid., p.25

[22] Installation shot of 1950: Aspects of British Art, Institute of Contemporary Arts, 1950 reproduced in Anne Massey, The Independent Group: Modernism and Mass Culture in Britain 1945-59, Manchester and New York 1995, p.29, pl.10

[23] Typescript sent to the Tate Gallery, 2 February 1965

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- landscape(1,191)

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- colour(2,481)

- irregular forms(2,007)

- countries and continents(17,390)

-

- Switzerland(1,058)

You might like

-

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Linear Abstract

1958 -

William Scott Ochre Still Life

1958 -

Ben Nicholson OM Feb 1960 (ice-off-blue)

1960 -

John Wells Painting

1962 -

Roger Hilton March 1960

1960 -

Patrick Heron Horizontal Stripe Painting : November 1957 - January 1958

1957–8 -

Roger Hilton Untitled

1971 -

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Composition February I

1954 -

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Red Form

1954 -

Peter Lanyon Wreck

1963 -

Stephen Gilbert Untitled

1948 -

William Gear The Sculptor

1953 -

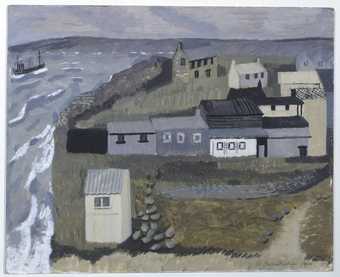

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Island Sheds, St Ives No. 1

1940 -

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham White, Black and Yellow (Composition February)

1957 -

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Rock Theme, St Just

1953