On loan

Auckland Art Gallery (Auckland, New Zealand): Light

- Artist

- William Blake 1757–1827

- Medium

- Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

- Dimensions

- Support: 445 × 594 mm

frame: 655 × 800 × 48 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

- Reference

- N05057

Display caption

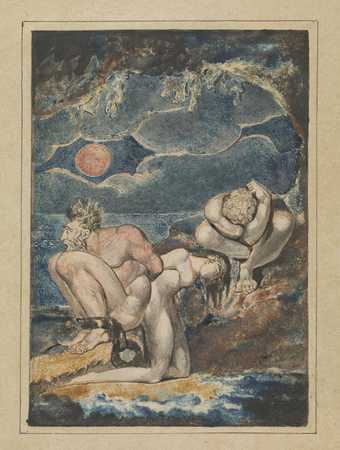

In his annotations to a text by Lavater, Blake claimed that ‘Active Evil is better than Passive Good’, rendering the figures in this picture somewhat ambiguous. Perhaps the chain attached to the ‘evil’ angel’s ankle suggests the curtailing of energy by misguided rational thought?

In constructing his figures, Blake evokes conventional eighteenth century stereotypes. The heavy build and darker skin of the ‘evil’ angel suggest a non-European character, described by Lavater as ‘strong, muscular, agile; but dirty, indolent and trifling’, while the fair hair and light skin of the ‘good’ angel are consonant with ideas of physical – and intellectual – perfection.

Gallery label, March 2011

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

N05057 The Good and Evil Angels 1795/? c. 1805

N 05057 / B 323

Colour print finished in ink and watercolour 445×594 (17 1/2×23 3/8) on paper approx. 545×760 (21 1/2×30)

Signed ‘WB inv [in monogram] 1795’ b.l. and inscribed ‘The Good and Evil Angels’ below design

Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

PROVENANCE Thomas Butts; Thomas Butts jun.; Capt. F.J. Butts; his widow, sold 2 June 1905 to W. Graham Robertson

EXHIBITED BFAC 1876 (202); Carfax 1906 (32); Tate Gallery 1913 (68); on loan to Tate Gallery 1923 onwards; Wartime Acquisitions National Gallery 1942 (7); English Romantic Art Arts Council tour 1947 (9); Tate Gallery 1947 (56); Tate Gallery 1978 (102, repr.)

LITERATURE Rossetti 1863, p.203. no.20, and 1880, p.209 no.22; Robertson in Gilchrist 1907, p.408, repr. facing p.142; Damon 1924, p.327; Figgis 1925, at pl.71, repr.; Preston 1952, pp.41–3 no.6, pl.6; Digby 1957, pp.38–9, pl.38; Blunt 1959, pp.42, 61–2, pl.31b; Butlin in Burlington Magazine, CVI, 1964, p.382; Beer 1968, pp.191, 256, pl.30a; Keynes Letters 1968, pp.117; Raine 1968, 1, pp.365–6, colour pl.120; Bentley Blake Records 1969, p.572; Kostelanetz in Rosenfeld 1969, pp.127–8; Warner in Erdman and Grant 1970, pp.184, 187; Mellor 1974, pp.120, 158–60, pl.43; Bindman 1977, pp.69, 98–9; Klonsky 1977, p.64, repr. in colour; Bindman Graphic Works 1978, no.328, repr.; Paley 1978, pp.38, 178, colour pl.32; La Belle in Blake, XIV, 1980–1, p.76, pl.9; Butlin 1981, pp.174–5 no.323, colour pl.400; Heppner in Bulletin of Research in the Humanities, LXXXIV, 1981, pp.388, 349–50; Raine 1982, at pl.53, repr.; Essick in Blake, XVI, 1982–3, pp.32–3; Warner 1984, pp.95–6, 102. Also repr: Mizue, no.882, 1978, 9, p.14 in colour

Listed in Blake's account with Thomas Butts of 3 March 1806 as ‘Good and Evil Angel’, having apparently been delivered on 5 July 1805. This is probably the second pull of the print, following that in the John Hay Whitney collection (Butlin 1981, no.324, pl.405). It could be one of the later pulls of c.1805, but if, as seems likely, it can be paired with ‘God Judging Adam’, it may date from 1795, as is supported by its general appearance. There is an earlier watercolour version of the composition, in reverse, probably painted c.1793–4, in the Cecil Higgins Museum, Bedford (Butlin no.257, colour pl.197).

The earliest version of the composition, however, also in reverse but on a smaller scale, occurs on page 4 of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, c.1790–3, where it appears to illustrate ‘the following Errors. 1. That Man has two real existing principles Viz: a Body & a Soul. 2. That Energy calld Evil is alone from the Body. & that Reason. calld Good. is alone from the Soul.3. That God will torment Man in Eternity for following his Energies’. Blake goes on to assert that the ‘following Contraries ... are True 1. Man has no Body distinct from his Soul ... 2 Energy is the only life and is from the Body and Reason is the bound or outward circumference of Energy. 3 Energy is Eternal Delight’. The design is thus an assertion of the error of dividing Man, originally unified, into his different elements, a concept that Blake developed and refined in his Lambeth Books, in which he symbolised these elements of the divided Man by different personifications. In the large colour print it is possible to identify the two main figures with two such personifications. The fettered figure is Orc, Blake's symbol for Energy, now older but demonstrably developed from the figure in ‘Los and Orc’, no.13, by way of the headpiece to the ‘Preludium’ of America (repr. Bindman 1978, no.148). As Mellor has demonstrated, Energy is now in 1795 seen as a negative force, a Urizenic will to power. The other figure is also a development of that in the earlier watercolour ‘Los and Orc’: Los, normally the personification of the Imagination, is also like Orc shown in his fallen state as a repressive force. The child is not paralleled in Blake's contemporary writings but may represent the lost innocence of the unified Man, now torn between the two fallen ‘angels’. As compared with the first version of the composition in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell the sun is lower in the sky, sinking below the horizon, another indication of Blake's increased pessimism at this time.

If one accepts the theory that Blake designed the series of large colour prints in pairs, this composition would seem to be the complement to ‘God Judging Adam’. In the latter ‘the flames of eternal fury’ emit no light, whereas in ‘Good and Evil Angels’ the fire represents energy as ‘the only Life ... Eternal delight’. Here light is positive, even if the scene shows one stage in the breaking up of Man into his different elements, while in ‘God Judging Adam’ the fire without light is part of a completely negative scene.

Published in:

Martin Butlin, William Blake 1757-1827, Tate Gallery Collections, V, London 1990

Explore

- objects(23,571)

-

- tools and machinery(1,287)

-

- chain(54)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- arm / arms raised(839)

- flying(173)

- man(10,453)

- baby(526)

- male(959)

You might like

-

William Blake David Delivered out of Many Waters

c.1805 -

William Blake Frontispiece to ‘Visions of the Daughters of Albion’

c.1795 -

William Blake Plate 4 of ‘Visions of the Daughters of Albion’

c.1795 -

William Blake Elohim Creating Adam

1795–c.1805 -

William Blake The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy (formerly called ‘Hecate’)

c.1795 -

William Blake The House of Death

1795–c.1805 -

William Blake Pity

c.1795 -

After William Blake Plate 3 of ‘Urizen’: Oh! Flames of Furious Desires’

date not known -

William Blake The Blasphemer

c.1800 -

William Blake The River of Life

c.1805 -

William Blake Los and Orc

c.1792–3 -

Edward Dayes The Fall of the Rebel Angels

1798 -

William Blake Satan Exulting over Eve

c.1795 -

William Young Ottley A Flight of Angels

date not known