Not on display

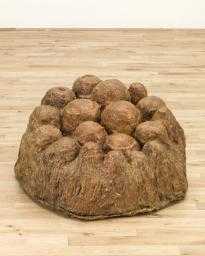

- Artist

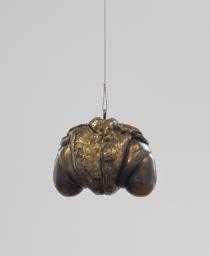

- Louise Bourgeois 1911–2010

- Medium

- Bronze, black patina

- Dimensions

- Object: 121 × 267 × 152 mm, 5kg. 7kg on bin.

- Collection

- ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2011

On long term loan - Reference

- AL00227

Summary

Tits is a bronze sculpture with a black, polished patina. The sculpture is curved and kidney-shaped, ending in two rounded points where the bronze shows through the patina. Bourgeois completed Tits in 1967 during a period in which she produced sculptural works that could be seen as abstract forms or depictions of body parts, often genitalia.

The title of the work, Tits, references female breasts and the sculpture could be read as two breasts fused together, with the non-patinated bronze at the tips representing the areolae. Yet the singularity of the object is also suggestive of a phallic form. This ambiguity is characteristic of Bourgeois’s work at this time. Indeed, she commented that she was keen to produce sculptures which could be read as indicative of either sex: ‘There has always been sexual suggestiveness in my work. Sometimes I am totally concerned with female shapes – clusters of breasts like clouds – but often I merge the imagery – phallic breasts, male and female, active and passive.’ (Quoted in Morris 2007, p.268.) Her interest in combining male and female body parts is more obvious in the sculpture Le Trani Episode 1971 (Hauser and Wirth, London), in which an object resembling Tits is overlaid by another more flaccid form. Again it is not clear that either object is gendered male or female as both parts have breast-like and phallic attributes. This anatomical ambiguity plays out, perhaps most famously, in Bourgeois’s Janus series, which consists of one porcelain and five bronze works that are displayed hanging in space. Janus Fleuri 1968 (Tate AL00347) has a similar basic form to Tits, with a more exaggerated arc and extended extremities that resemble the foreskin or glans. At the centre of the object, the smooth surface appears to have ruptured, revealing a bumpy terrain with a central crevasse suggestive of a vulva. The reference in the title to Janus, the Roman two-faced god, alludes to androgyny as much as opposition between the sexes.

Tits, like Janus Fleuri, may be seen to exemplify a ‘part-object’, a term used by psychoanalysts to refer to parts of the body that attest to physical and emotional relationships between infants and adults. The art historian Mignon Nixon has written about the part-object and its influence on Bourgeois’s work. Nixon has argued that by fragmenting parts of the body, creating ‘part-objects’, Bourgeois represented their physiological and sexual characteristics, gesturing to the complex and conflicting attachments we have to our own bodies and the bodies of others. The critic Rosalind Krauss has also written on this theme, looking specifically at the breast in relation to Bourgeois:

For the newborn, suckling divides the mother’s breast from its bodily support, separating the organ from her as the target to satisfy the infant’s needs. The world of the infant splinters into such part-objects: its own desiring organs as well as their reciprocal targets: so many breasts, mouths, bellies, penises, anuses.

(Quoted in Morris 2007, p.200.)

When speaking of similar works produced around the same time as Tits, Bourgeois appeared to justify Krauss’s interpretation: ‘I made a drawing of breasts pressed against each other; there was a double attitude to be like a mother, and to be liked by a mother … the lips like sucking. The whole person becomes a breast that stretches in order to give.’ (Quoted in Duncan Macmillan, ‘Blood Ties’, Modern Painters, May 2008, p.75.)

Further reading

Mignon Nixon, Fantastic Reality: Louise Bourgeois and a Story of Modern Art, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London 2005.

Frances Morris (ed.), Louise Bourgeois, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London 2007.

Lucy Askew and Anthony d’Offay, Louise Bourgeois: A Woman Without Secrets, exhibition catalogue, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh 2013, p.92, reproduced p.35.

Allan Madden

The University of Edinburgh

February 2015

The University of Edinburgh is a research partner of ARTIST ROOMS.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- figure(2,270)

- social comment(6,584)

-

- gender(1,689)

You might like

-

Louise Bourgeois Nature Study

1986 -

Louise Bourgeois Single II

1996 -

Louise Bourgeois Janus Fleuri

1968 -

Louise Bourgeois Fallen Woman

1981 -

Louise Bourgeois Fillette (Sweeter Version)

1968–99, cast 2001 -

Louise Bourgeois KNIFE COUPLE

1949 -

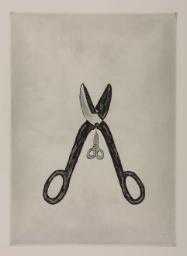

Louise Bourgeois Scissors

1994 -

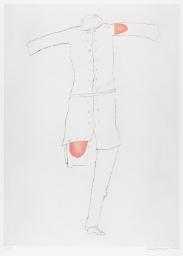

Louise Bourgeois Amputee

1998 -

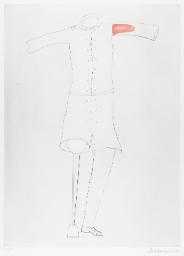

Louise Bourgeois Amputee with Peg Leg

1998 -

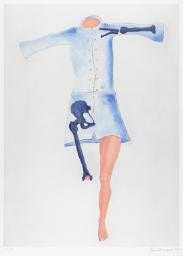

Louise Bourgeois Blue Dress

1998 -

Louise Bourgeois Cell (Eyes and Mirrors)

1989–93 -

Marcel Duchamp Female Fig Leaf

1950, cast 1961 -

Louise Bourgeois Amoeba

1963–5, cast 1984 -

Louise Bourgeois Avenza

1968–9, cast 1992 -

Louise Bourgeois Mamelles

1991, cast 2001