Not on display

- Artist

- Gillian Carnegie born 1971

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 1934 × 1932 × 33 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by Tate Members 2010

- Reference

- T12935

Summary

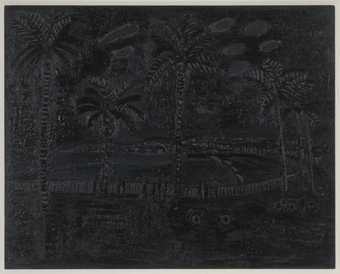

Black Square is a monochrome black painting depicting the trunks and branches of a clump of trees in textured paint. The image derives from a photograph taken by Carnegie at Hampstead Heath in North London. The painting surface is intensely tactile, combining matt and glossy paint, while the heavy black impasto makes it hard to decipher the brush’s linear markings on the surface, relying on external lighting and the viewer’s own movement to fully reveal the image.

Black Square is one in an ongoing series of monochrome black paintings, begun in 2000 with Honer, that explores variations on the same theme – a night view of a landscape. The painting takes its title from an earlier version, Black Square 2002 (reproduced in Tufnell, p.49 and Carey-Thomas, [p.7]). The title makes explicit reference to the Suprematist painting Black Square 1914–5 (State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) by Russian artist Kasimir Malevich (1878–1935). Regarded as an icon of early modernism, the intense abstraction exercised by Malevich in Black Square suggested a ‘world without objects’ and ‘was the first step in the pure creation of art’ (Kasimir Malevich, ‘From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Realism in Painting’, Essays on Art 1915–1933, Vol. I, London 1971, p.38). Following Malevich’s invention, Carnegie’s monochrome black paintings take the viewer to the limits of what is visible, but as opposed to her predecessor, Carnegie’s original impetus for these works ‘was the challenge of depicting a night scene, rather than as a conscious referencing of the monochrome tradition in painting’ (Tufnell, p.48). The figurative content of Carnegie’s Black Square subverts the early twentieth century claims to the end of illusionism in painting and the creation of a new multidimensional and infinite space as a new realisation of reality. In this series, Carnegie follows this modernist tradition by drawing attention to the physical qualities of the painting and emphasising its status as an object. However, unlike the early modernist tradition of monochrome painting, she does not do this through the introduction of geometric and non-referential forms, but by emphasising the painting’s materiality through her use of it to describe a representational image. Crowded with texture and visual information, Carnegie’s monochrome series is closer in one respect to the tradition of monochrome black painting developed in New York during the 1950s. The paintings in this series partially echo The Black Paintings 1951–3 by American artist Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), which were constructed with layers of newspapers, crumpled, folded and pasted on to the canvas surface and coated with thick layers of enamel, creating an alternately matt and glossy surface that reflects light unevenly. Carnegie’s figurative and textured representation takes Rauschenberg’s abstraction one step further.

Working on different series as a painterly exercise, Carnegie plays with the conventions of academic figurative painting and the genres of still life, landscape, the nude and portraiture. It is significant that the sources for her paintings are photographs that she has taken herself, and that the genres of painting she uses as motif do not include narrative or history painting, and provide subjects that can be treated in themselves as academic exercises in painting. The visceral qualities of paintings such as Black Square

articulate Carnegie’s ‘obsession with exploring the construction of potent images from the base materiality of paint’ (Staple, p.75). The abundance of paint, its indefinite and messy forms, makes the painting’s materiality present at all times, while the use of only one colour draws the viewer’s attention to the way in which the artist has literally built the image out of paint, through a variety of brush strokes. In Carnegie’s work the contradiction between matter and image is never resolved; on the contrary, it is precisely this contradiction that informs the works.

Further reading:

Lizzie Carey-Thomas, ‘Gillian Carnegie’, Turner Prize 2005, exhibition brochure, Tate Britain, London 2005 [pp.6–7].

Ben Tufnell, ‘Gillian Carnegie’, Days Like These, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2003, pp.48–53.

Polly Staple, ‘The Finishing Touch’, frieze, number 64, January–February 2002, pp.72–5.

Carmen Juliá

April/May 2009

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- monochromatic(722)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- texture(466)

- UK countries and regions(24,355)

-

- England(19,202)

You might like

-

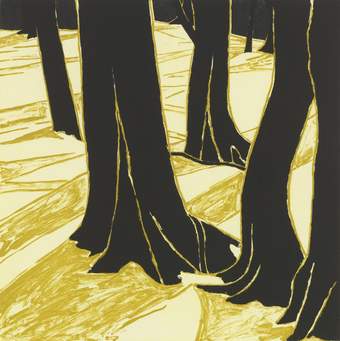

Gillian Carnegie Black Square

2004 -

Gillian Carnegie Hotel

2004 -

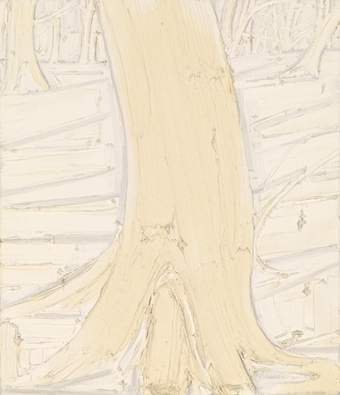

Gillian Carnegie White on White

2007 -

Gillian Carnegie Voi

2004 -

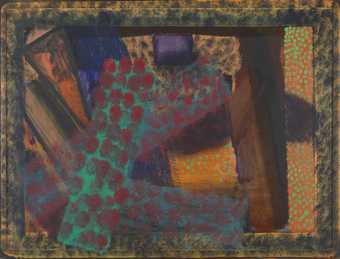

Howard Hodgkin Dinner at Smith Square

1975–9 -

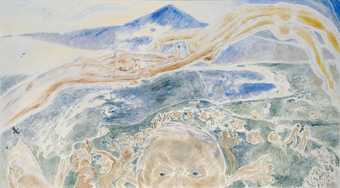

Jeffery Camp Southcoast

1990 -

Lisa Milroy Finsbury Square

1995 -

Maggi Hambling Father, Late December 1997

1997 -

Sigmar Polke Untitled (Square 2)

2003 -

Keith Coventry East Street Estate

1994 -

Keith Coventry Black Crack Pipes

1999 -

Keith Coventry Beach at Nice V

2005 -

Gillian Carnegie Hanser

2010 -

Gillian Carnegie Untitled

2008 -

Maggi Hambling 2016

2016