Not on display

- Artist

- John Davies born 1946

- Medium

- Polyester resin, fibreglass, wire, beads and steel

- Dimensions

- Object: 305 × 203 × 394 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1972

- Reference

- T01578

Display caption

This work is based on a cast taken from the head of a living model named William Jeffrey. Casting from life involves encasing the sitter's head in wet plaster. After this has hardened, the resulting mould is taken apart in sections, and from this a cast in fibreclass is made. The advantage of this process is that an exact facsimile of the subject's features is obtained. Despite their precision, Davies has observed that life casts communicate little about the subject's character. Also, this realistic cast incorporates the strange addition of cones of chicken wire placed over the face. Consequently, this head does not characterise an individual, but represents human personality in general.

Gallery label, August 2004

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

John Davies b.1946

T01578 William Jeffry with Device 1972

Not inscribed.

Painted polyester resin, fibreglass and inert fillers, 12 x8 x 15½ (30.5 x 20.3 x 39.4).

Purchased from the artist through the Whitechapel Art Gallery (Grant-in-Aid) 1972.

Exh: Whitechapel Art Gallery, June–July 1972 (16,repr.).

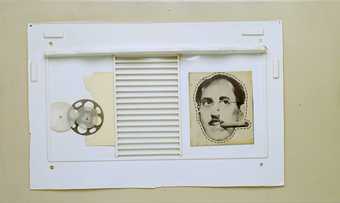

‘William Jeffrey with Device’ is a life-size head of a man, painted flesh colours, over which are fixed two blue cones of chicken wire, one over the head overlapping one on the back. Five imitation pearls are suspended from the cone before the face, three behind. Lead fishing weights are attached to the wire. The head is placed on a 1 in. diameter metal pole, 68 in. high.

The sculpture is based on a life cast made of William Jeffrey’s head in 1972. A series of heads resulted from this cast, of which five were completed, all entitled ‘William Jeffrey with Device’. T01578 was the third in the series and had perhaps the most complex of the devices used. The ‘devices’ on the other four are: one, chicken wire, stretched over a wire frame, over a horn shape which covered the nose, forehead and mouth but which left the eyes visible; two, a horn-like form from between the eyes covering the nose and part of the mouth, with feathers round the outer rim of the form; three, two pieces of dowelling, one resting horizontally on the bridge of the nose, the other parallel to this on the tip of the nose; both were fixed by wire round the ears, and the eyes look out in the space between the dowelling; four, a hat made of felt and coated with oil paint, a painted leaf-like structure over the nose with pieces cut out so that the eyes are visible.

The artist made a mould of the subject’s head with plaster-bandage and then cast the head into a resin and fibreglass shell. Davies finds the polyester resin an unpleasant material and he adds the fillers and pigment to disguise its synthetic appearance. He initially painted the head to a high degree of realism but found this unconvincing and unsatisfactory. He realised that other means were necessary which did not involve any actual distortion of the features. In this way the use of a ‘device’ became necessary—a means by which the head could remain intact and undistorted and the device could be the thing that was altered to affect the head. He tried many different ways and ‘devices’ until he found the head was beginning to be less an object and more a person. The device had the effect of making something occur between it and the head, which produced a human aspect, more apparent than when it was not there. Jeffrey first sat as a life mask model for Davies in 1972. Like the sculptures of other sitters, Davies’ brother, his friends, and often complete strangers, the work is not intended to be a portrait of a particular subject but rather of human personality in general.

Since he began to produce more realistic sculpture Davies has worked both by modelling and by casting life masks. However, Davies finds that neither technique is satisfactory. The finely detailed life cast which ought to be a successful way of making an image of a person, turns out not to be. When he is modelling heads he thinks that the heads have too much the appearance of a made object and qualities not shared by people, that is the qualities of the object’s material and style. Davies wants the ‘unremarkable’ naturalism provided by life casts. He works on the surface of the cast, altering but not distorting the features. Often casts seem to him too detailed and perfect and to have that quality of photographs where there is an excess of detail compared with the impression one would have by just looking. Such casts are the most difficult to work on and the less specific ones are often the easiest to adapt and change. Davies is often surprised that although life casts may be precise records of all the physical details of a person they communicate so little about a person.

One of the differences between Davies’ sculptures of heads and of the fully clothed figures and groups is that the heads are intended to lack a context and to be independent of any defining event or relation.

The artist wants ultimately to achieve a sculptural style that is as realistically acceptable and unremarkably real as the life cast but is achieved solely by modelling. Since he is making figures he would like them to have the qualities of people to such a degree that the sculptural qualities, whatever may indicate it is made may disappear, and the spectator is only aware of the person before him and not conscious that it is the product of a particular style, time or artist.

Published in The Tate Gallery Report 1972–1974, London 1975.

Explore

- objects(23,571)

-

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

- head / face(2,497)

- individuals: male(1,841)

You might like

-

Ivor Roberts-Jones Paul Claudel

c.1955–7 -

Tim Scott Quadreme

1966 -

John Davies Dogman

1972 -

John Davies Young Man

1969–71 -

John Davies Head with Blue Eyes

1983–4 -

Colin Self Hot Dog Sculpture

1965 -

Robert Adams Space Construction with a Spiral

1950 -

Dame Elisabeth Frink Goggle Head

1969 -

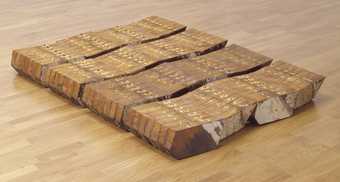

Cornelia Parker CBE RA Thirty Pieces of Silver

1988–9 -

Liliane Lijn Space Displace Koan

1969 -

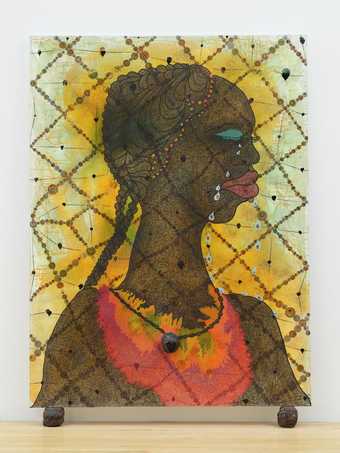

Chris Ofili CBE No Woman, No Cry

1998 -

John Davies The Redeemers

1971 -

Achill Redo (Anthony Hill) The Indian Robe Trick

c.1991–3 -

Garth Evans Convoy

1979 -

Victor Newsome Two Craters (Two Blind Holes)

1963