Lala Rukh

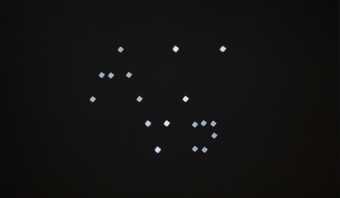

Still from Rupak 2016

Video, projection, colour, sound (stereo) and 88 works of ink on paper

Object, each: 162 × 215 mm

Animated film duration: 6min, 12sec

© Estate of Lala Rukh and Grey Noise, Dubai

Rupak 2016 is the last major work made by the Pakistani artist Lala Rukh (1947–2017). It consists of an animation and eighty-eight drawings, combining sound, movement and calligraphy to visually synthesise a taal, a seven-beat musical cycle played on the tabla, a pair of small hand drums. The work is currently on show at Tate Modern as one of eight pieces in Performer and Participant, a display of artworks thematising political participation by artists working between the 1960s and the 1990s.

Rupak and its theoretical origins were at the heart of the event Lala Rukh’s Life and Legacy: A Panel Discussion, which was held online due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The event brought new considerations to Lala Rukh’s work and highlighted multifaceted dimensions of her life and legacy. The discussion was introduced and moderated by Devika Singh, Curator of International Art at Tate, who curated the display of Rupak at Tate Modern. The three speakers were: Mariah Lookman, an artist and educationalist based in Galle, Sri Lanka, who was taught by Rukh; Ayesha Jatoi, an artist and editor based in Lahore, who was also Rukh’s student; and Natasha Ginwala, curator at Gropius Bau in Berlin, who worked with Rukh to bring her work to Documenta 14 in 2017. A central theme that anchored the discussion was the inseparability of Rukh’s art from its activism. The insightful papers traced Rukh’s artistic journey towards developing a rigorous concision of form, constantly grounded in the particular within the universal, to finally arrive at the visualisation of a musical unit represented by a qat – a diamond shaped mark from a calligraphic pen.

Considering Rukh’s life-long activism as a founding member of the revolutionary Women’s Action Forum (WAF) in Pakistan, this arrival appears portentous – unlike the vocal improvisations of an alaap (another key element of Hindustani classical music), the beat cycle of the taal works as a democratic musical unit. A beat lends itself as a common constituent in the music of the many, and that of resistance, including hip-hop; beats are the fundamental elements of the soundscape of protest, of songs and slogans. Rukh’s paring down of music to animate a beat in Rupak manifests her eclectic personhood; she was variously a photographer, archivist, poster artist, educator and activist in countless movements, and distinct narratives about each of these roles emerged from the three presentations at this event.

Lala Rukh

Mirror Image 1, 2, 3 1997

Mixed media on graph paper

48 x 60 cm

Grey Noise, Dubai

© Estate of Lala Rukh and Grey Noise, Dubai

In her presentation ‘Lala Rukh’s Camera: Listening with Photography and Drawing the Space of Time’, Mariah Lookman posited that Rukh’s early photographic work in archiving political movements was foundational to her artistic practice. Lookman’s comparison revealed the power of photographic evidence in the hands of both the oppressed and the oppressor. She presented Rukh’s photographs of women’s marches and protests as acts of bearing witness – particularly those taken in Lahore in 1984 against Article 17 of the Law of Evidence, which declared a woman’s testimony to be worth half that of a man. Rukh was also an activist-citizen and archivist of political action against the forced Islamisation of law under General Zia-ul-Haq’s military dictatorship in Pakistan (1978–88). Lookman suggested that this archival work made Rukh understand the ‘nature of power and the power of images’. Consequently, this influenced Rukh’s later work Mirror Image 1, 2, 3 1997, a set of drawings in mixed media where she depicts the violent demolition of Babri Masjid in India and the desecration of temples in Pakistan through the ‘darkening’ of graphic newspaper clippings. Lookman’s reading of Rukh’s artistic obfuscation of images gains heightened relevance in light of recent events. Babri Masjid, a historic mosque in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh was demolished by Hindu mobs in 1992. Several of the accused were leaders of India’s ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), who claimed the site as the birthplace of the mythical Hindu god Ram. This ruptured the already fragile relations between Hindus and Muslims leading to violent riots in India. The event anticipated the virulent Hindu nationalism of contemporary India that has normalised the paradoxical treatment of evidence in legal institutions, where myth-based belief is supported as evidence for the foundation of a temple and simultaneously, those accused of involvement in the violent demolition are acquitted. Here, Rukh’s act of ‘hiding’ becomes a critique of authoritarian power that refuses visual evidence of the violent event.

Lala Rukh (far left) burning a chador (a cloak-like cloth that covers the head) during a demonstration organised by the Women’s Action Forum in Lahore, 1987, in protest of the killing of two sisters in Karachi

© Azhar Jaffery

Rukh’s journey towards a sparseness in mark-making that eventually arrived at the unit of measure of qat was preceded by a rich repertoire of undocumented work across various media. In her presentation ‘Of Sounds and Silences’, Ayesha Jatoi quoted Rukh describing this transition: ‘this is when I had the courage to disappear’. Jatoi discussed the unarchived Rukh – her revolution in crafting not only the art, but also the means to develop and sustain diverse art forms. Jatoi detailed Rukh’s photographic documentation over three decades of resistance, and included in Rukh’s repertory the posters, leaflets and banners that she designed in the early days of WAF. Rukh’s work in digitising the archives of the All Pakistan Music Conference, founded by her father Hayat Ahmad Khan, included the documentation of folk and classical music as well as the designing of covers of CDs and catalogues. Jatoi remembered Rukh as a formidable educator who encouraged her students to tap into the artistic reservoir of the Indian subcontinent – oral traditions, miniature painting, calligraphy – practices that transcended the enforced nationalisms brought about by brutal partition. Rukh’s own training in calligraphy would eventually lead to the visual form animated in Rupak.

Ginwala worked with Rukh to curate the inaugural display of Rupak at Documenta 14 at Athens Conservatoire (Odeion) in 2017, the year of Rukh’s death. In her presentation ‘Lala Rukh: Still Point in the Turning World’, she described Rukh’s final experiment in which she allowed her lifelong immersion in sound and music – Hindustani classical and folk; jazz and blues encountered in Chicago in the 1970s – to synthesise with animation. Ginwala interpreted an interesting co-dependence between the artwork and the space of its curation at Documenta: it was shown in a music conservatory and addressed the ‘language of scores’ and ‘deep listening’ and also the ‘artist’s role in inventing music instruments’. This harmonised well with Rupak’s aesthetic and creative concerns; it complemented Rukh’s body of work as an artist and educator who held a deep regard for artistic ‘making’, relentlessly bridging the perceived gap between conceptual art and craft. Ginwala further drew out resonances with artist and author Denise Ferreira da Silva’s ‘poethics of blackness’, reading a consistency in the black of Rukh’s palette in the River in an Ocean series 1992, Hieroglyphics IV 2006 and Rupak. In her essay ‘Toward a Black Feminist Poethics: The Quest(ion) of Blackness Toward the End of the World’, Ferreira da Silva writes of the need to recuperate Blackness from its categorical existence as ‘always already’ an object, commodity and other.1 She proposes a reimagination of Blackness as radical possibilities of ‘knowing, doing, and existing’. Ginwala reads a similar paradigm in Rukh’s use of black – as radical hope in ‘a world witness to extreme injustice’, Rukh’s black was always already ‘surplus’, an archive of the ‘unscripted’ and an imagination of latent ‘possible futures’.

Given that the speakers had known Rukh closely as students and curators of her work, their personal anecdotes brought out the familiar and private Rukh. They remembered her as a dedicated teacher, an avid collector of an eclectic musical range spanning from Sara Zaman to Fela Kutti, and the joy of full immersion as an artist that she relished in the final years of her life. The panel discussion established Rukh as a transnational (and transregional) artist, whose artistic practice and activism through WAF spanned across Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and India. The speakers also addressed Rukh’s thorough grounding in the historical legacy of Lahore, a 1000-year-old city, and her rich contribution to it. The fact that her subversive practice in a highly repressive context – she practised life drawing using a male model in the 1970s, for instance – was only possible due to her class privilege was mentioned by the panelists, but not adequately addressed. A discussion of class and art practice would have revealed the networks through which particular art forms become cultural capital. Most importantly, it would help to de-centre the narrative of a singular detached artist as a figure of influence and uncover the contributions of often sidelined (or erased) grassroots artists to workers’ and women’s protests on the Indian subcontinent.

Screenshot from the online event Lala Rukh’s Life and Legacy: A Panel Discussion, with (clockwise from top left) Devika Singh, Mariah Lookman, Natasha Ginwala and Ayesha Jatoi

Current measures of social distancing and avoidance of public spaces may have hindered viewers’ personal engagement with Rupak at Tate Modern, but the panel discussion brought to screens rich interpretations of the work. Ginwala highlighted Rupak’s relevance to the difficult times of the present: the way in which the artwork unfolds in relative isolation from its potential audience during lockdown, politically engaged in archiving the unscripted in the pauses between its monochromatic pulsebeats, is like much of Rukh’s private artistic practice. It necessitates, as Ginwala reads in Rupak, a ‘rigorous discipline of keeping pace’, emblematic of the spirit of active citizenry that negotiates daily the uncertain times brought by the pandemic – a citizenry consistently engaged in an ‘unfinished pursuit of mourning’ (Ginwala), as a political act to mark the colossal loss of lives worldwide.