Not on display

- Artist

- Maggi Hambling born 1945

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 1448 × 1222 mm

frame: 1575 × 1347 × 50 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1987

- Reference

- T05023

Catalogue entry

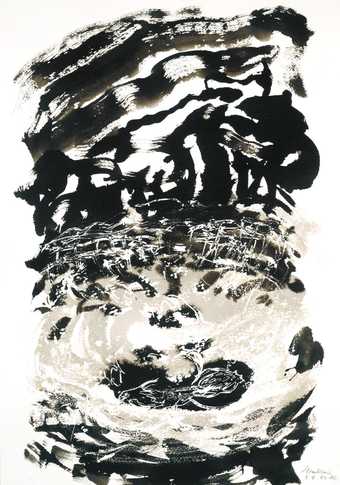

T05023 Minotaur Surprised while Eating 1986–7

Oil on canvas 1448 × 1222 (57 × 48 1/8)

Inscribed 'HAMBLING |‘86–‘87’ on back of canvas top centre

Purchased from the artist (Grant-in-Aid) with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1987

Exh: Maggi Hambling: Paintings, Drawings and Watercolours, Serpentine Gallery, Oct.–Nov. 1987 (54, repr. pl.11 in col. and on private view card); Modern Painters: A Memorial Exhibition for Peter Fuller, Manchester City Art Galleries, March–May 1991 (18, repr. front cover in col. and p.19 in col.); Maggi Hambling: An Eye through a Decade 1981–1991, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, July 1991 (12)

Lit: Peter Fuller, ‘Maggi Hambling's Minotaur Surprised while Eating’ and Marina Warner ‘Maggi Hambling’ in Maggi Hambling: Paintings, Drawings and Watercolours, exh. cat., Serpentine Gallery 1987, pp.25–6, 96, repr. pl.11 (col.); Mary Rose Beaumont, ‘Maggi Hambling’, Arts Review, vol.39, Oct. 1987, p.689; George Melly, ‘Maggi Hambling’, Art Line, vol.3, no.9, Oct. 1987, p.34; William Packer, ‘Of Sacred Beasts and Bullish Things’, Financial Times, 20 Oct. 1987, p.15; Jonathan Watkins, ‘Maggi Hambling’, Art Monthly, vol.110, Oct. 1987, p.13, repr.; Peter Fuller, ‘Maggi Hambling’, Burlington Magazine, vol.129, Nov. 1987, pp.760–1, repr. (col.); Tate Gallery Report 1986–8, 1988, p.96 (repr. in col.); Elaine Feinstein, ‘A Profile of the Artist’, Modern Painters, vol.1, no.2, Summer 1988, pp.27–32; Peter Fuller, ‘Maggi Hambling’ in Modern Painters: A Memorial Exhibition for Peter Fuller, exh. cat., Manchester City Art Galleries 1991 pp.16, 18; Mel Gooding, ‘An Eye through a Decade 1981–1991’ in Maggi Hambling: An Eye through a Decade 1981–1991, exh. cat., Yale Center for British Art, New Haven 1991, p.9

This painting depicts the Minotaur, a mythical beast, with a slab of human flesh dripping blood in his hands, and some in his mouth. The creature stands in an area of ambiguously defined space against a boldly striped orange and blue background. The Minotaur, or bullman, was in classical Greek myth the progeny of a union between Pasiphae, the wife of King Minos of Crete, and a handsome white bull which Minos had refused to sacrifice to the god Poseidon. Angered by this refusal, Poseidon caused Pasiphae to fall in love with the animal. Pasiphae confessed her love to Daedalus, the famous Athenian craftsman who was living in exile at Knossos in Crete. Daedalus built for Pasiphae a hollow wooden cow which was placed in the meadow near Gortys, where the white bull was grazing. The bull mounted the hollow cow with Pasiphae concealed inside and she later gave birth to the Minotaur, a monster with a bull's head and a human body. King Minos then consulted an oracle to enquire what to do about his wife and the monster. The oracle instructed him to build a retreat at Knossos. Daedalus constructed a labyrinth near to Minos's palace at Knossos and the Minotaur was concealed within it. Minos then decreed that as an annual tribute seven young men and seven maidens should be sacrificed to the Minotaur, and the victims were sent into the labyrinth, never to escape. In T05023 the Minotaur is shown eating the flesh of one of these sacrificial human victims.

T05023 was painted in the artist's Clapham studio during a period of about three months, at the end of 1986 and the beginning of 1987. Hambling worked only on this one painting during that period. T05023 was prepared by the artist in what was then her usual manner: the cotton duck support was primed with three coats of rabbit skin size, which gave it an ivory-yellowish colour (Hambling disliked using a white priming, as she felt that white was a very powerful colour). All Hambling's paintings on canvas are executed in oils. She dislikes working with acrylic paint, finding that it lacks sensuality. As she paints, ‘all the paint goes on extremely fast; if it is not right, then it comes off’ (statements by the artist cited in this entry are taken from conversations with the compiler on 7 December 1988 and 5 June 1990). She uses brushes of various sizes, cloths, her fingers, and sometimes a painting knife to make marks of diverse kinds.

In 1977 Hambling attended a bull-fight in Madrid when on a working visit to that city to study the paintings of Goya. She had decided to go to a bullfight to see if she could stand the spectacle. She began by covering her eyes for the first three fights, unable to watch, and then felt strong enough to look at the event directly. She learnt that, prior to the fight, the bull lived for five years at pasture, enjoying a good, free life. It was then transported and confined in the dark for only the twenty-four hours prior to the fight. In her mind she compared the fate of the Spanish bull with that of hens in British battery farms and in both cases felt concern for the degradation of innocent animals, exploited by humans. She concluded, however, that the bull had the better deal, given its five years of freedom in comparison to the battery hen, whose entire life was spent in a tiny crowded cage.

In 1986 this concern over the factory farming of poultry led Hambling to make a painting titled ‘Battery Hen’, 1986 (private collection, repr. John Moores Liverpool Exhibition 15, exh. cat., Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool 1987, no.51). The artist said of this work: ‘In this painting, a cramped, de-feathered, caged hen challenges the viewer by the defiant, unquenchable spirit in its eye.’ The painting was done from memory and imagination rather than from life.

In 1985 Hambling returned to Spain and stayed in Barcelona, to look at work by Juan Miró and Antonio Gaudí, and on this visit she went again to a bullfight. This time she not only watched the action but also drew it. This second experience of a Spanish bullfight resulted in a series of six paintings of bullfights and wounded bulls, as well as two paintings concerning the Greek myth of the Minotaur, one of which is T05023. These eight paintings were executed in the following order:

‘Descent of the Bull's Head’, 1985

1600 × 1220 (63 × 48), Swindon Art Gallery (repr. Serpentine Gallery exh. cat., 1987, pl.6 in col.)

‘Fallen Bull’, 1985

1700 × 1500 (67 × 59), the artist (repr. ibid., pl.7 in col.)

‘Pase de Pecho’, 1986

1220 × 1140 (48 × 45), destroyed by the artist in 1988

‘Minotaur Surprised while Eating’, 1986–7, T 05023

‘Dead Bull’, 1987

940 × 760 (37 × 30), private collection, London (repr. ibid., pl.8 in col.)

‘Pasiphae and the Bull (Conception of the Minotaur)’, 1987

1600 × 1450 (63 × 57), private collection, USA (repr. ibid., pl.12 in col.)

‘5th Bull’, 1987

1295 × 1140 (51 × 45), private collection, London (repr. ibid., pl.9 in col.)

‘6th Bull’, 1987

1450 × 1220 (57 × 48), private collection, London (repr. ibid., pl.10 in col.)

There have been no more paintings with the subject of the bull since 1987. However, Hambling made two more drawings on the theme, both in charcoal. They are:

‘Dying Bull’, 1987

839 × 597 (33 × 23 1/2), private collection, London (repr. Maggi Hambling: Moments of the Sun, exh. cat., Arnolfini, Bristol 1988, p.24)

‘Cornered Bull’, 1988

559 × 762 (22 × 30), private collection, Bristol (repr. ibid., p.25)

On being questioned about the genesis of T05023, Hambling realised that two of the earlier bull paintings, ‘Fallen Bull’ and ‘Pase de Pecho’, both played significant roles. The composition of ‘Fallen Bull’ contains a wounded bull in the lower half with two legs belonging to two separate toreadors above. A foot and a hand of another toreador appear from the left. ‘Fallen Bull’ is therefore the first of the bull paintings to include the presence of human beings. ‘Pase de Pecho’, which has now been destroyed, was a painting ‘all about the dance of the bull and the man, together making one image. The bull was on its back legs with its forelegs up in the air.’ The bull was in the centre of the composition with the man on the right, and both were depicted standing upright. Hambling was occupied with the painting of ‘Pase de Pecho’ for a long time, finding it a great battle. She was not satisfied with the work and did not include it in her Serpentine Gallery exhibition in 1987, even though it was listed as no.50 in the catalogue. In discussing the origins of T05023, Hambling realised it was ‘born out of the struggle of “Pase de Pecho”’.

Prior to the painting of T05023, three small preparatory drawings of the figure of the Minotaur were made in an A4 sketchbook in use during 1986–7. These were interspersed with pages of life drawing from the nude model. The Minotaur drawings were executed using a stick of graphite with a thick blunt end. They were made in order to work out the balance of the awkward stance of the Minotaur, who, being half-man and half-animal, was not given, Hambling felt, to standing only on his hind legs. The first drawing depicted the Minotaur standing, facing forwards and leaning to the left, as in T05023, but with his arms hanging loosely in front of his body. A pentimento reveals that the Minotaur's left arm was originally crooked across his body and his hands were clasped. A second drawing showed the Minotaur standing and holding human flesh as in T05023, while the third depicted him standing facing forwards, leaning to the right, with his arms hanging loosely before him. The sketchbook containing these drawings was placed on a stool in the studio, open at the page with the second drawing, and with this as a reminder, Hambling started painting the composition of the ‘Minotaur Surprised while Eating’ directly onto the canvas. The artist said of this process: ‘the drawing is there as a first expression of the idea which is then created in paint.’ The second drawing, which led to T05023, was subsequently removed from the sketchbook and shown in the artist's 1987 Serpentine Gallery exhibition (no.46, dated 1986) where it was included in the section called ‘Sketch Book Drawings’ and titled ‘Study for Minotaur’ (private collection, London). The other two are still in the artist's possession. None of these drawings has been reproduced.

When asked by the compiler about her strong and continuing interest in painting animals, Hambling recalled that the first exhibition that she ever attended, at the age of about four or five, was of paintings of bulls. The exhibition was held in a first floor room of a public house in her home town of Hadleigh, Suffolk. She was taken by her mother and remembered being ‘amazed’ by these paintings of bulls. The painter was Tony Stoney, a local farmer, who had painted portraits of bulls for her farming friends. Concurrent with the bull paintings of 1986–7, Hambling also painted the following works containing animals: ‘Battery Hen’, 1986 (mentioned above); ‘Percy, 3 Months’, 1986; ‘Welsh Black with Sores’, 1986; ‘Percy Jumping’, 1986 (repr. Serpentine Gallery exh. cat., 1987, back cover in col.); ‘Welsh Black Heifer (Self-Portrait)’, 1986 (repr. ibid., pl.5, detail); ‘Battersea Park Herons, October’, 1986–7; and ‘Cygnet’, 1987. Percy is Hambling's black-and-tan terrier and constant companion.

The two paintings of Welsh Black cows stem from a painting trip Hambling made to Wales in 1986, during which she found herself ‘very moved by these Welsh Black Heifers, the saddest cows I'd ever seen’. ‘Welsh Black Heifer (Self-Portrait)’ was based on a colour photograph of one these animals, specially taken for Hambling to work from. When the work was completed, Hambling added the subtitle ‘Self-Portrait’ partly as a joke, noticing that the animal she had painted had curly hair and long eyelashes, two of her own dominant facial characteristics. On further reflection, Hambling found that the ‘Self-Portrait’ part of the title was significant, because ‘what an artist does is to look at things’ and these Welsh Black cows ‘have a very intent look when they look at you’. Hambling concluded that ‘the cow's activity was also my activity’, deciding to retain the originally flippant subtitle. The concentrated gaze of the heifer is matched by that of a bull in Hambling's painting ‘Descent of the Bull's Head’, 1985 and by that of the Minotaur in T05023. The composition of ‘Descent of the Bull's Head’. is made up from four separate renderings of the animal's head seen at different angles, from erect to wounded, as it falls dying to the ground. The second head portrays the bull looking straight out and the artist said of this work that ‘it was a challenge not to make it sentimental’. The gaze of the Minotaur in T05023 has the same intensity, and Hambling finds that ‘this confrontation between subject and artist/viewer is important’. By describing the Minotaur as ‘surprised’ in the act of eating, Hambling's title makes this relationship explicit. The direct gaze is something which she has also exploited in some of her portraits, and in conversation with the compiler Hambling drew attention to the painting ‘Max Wall and his Image’, 1981, in which the sitter looks straight out at the viewer (T03542, repr. Max Wall: Pictures by Maggi Hambling, exh. cat., National Portrait Gallery 1983, p.9).

In the light of the link between the confrontational gaze in both ‘Welsh Black Heifer (Self-Portrait)’ and ‘Minotaur Surprised while Eating’, Hambling was asked if there was any hint of self-portraiture in the latter work. She replied that she identified with the ‘primitive’ nature of the creature: ‘An artist identifies with what he or she paints; you become the thing you paint.’ Hambling felt that the Greek myth of the Minotaur presented him as a monster, and that she did not feel this way about the mythical animal, having, on the contrary, great sympathy for his state. ‘It was not his fault that he was born the Minotaur, and had to live a solitary life, with no mate, eating sacrificial human flesh.’ He was, according to the artist, ‘a child of the Gods’.

When Hambling made the decision, on the strength of the sketchbook drawing, to produce a painting of the Minotaur, she turned to a reference book in her library, The New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, 1968, to check the details of the mythological story and to see how the creature had been depicted in the past. There was no reproduction in that book of the Minotaur shown in the act of eating human flesh. Hambling is adamant that her representation of the beast doing so is not to be read as some sort of a statement about meat-eating versus vegetarianism. The title of the work is straightforward and simply describes what is happening. Hambling's sympathy for the plight of the Minotaur led her to try to paint the creature ‘with humanity’. His appetite for human flesh was an instinctive one. Hambling commented, ‘We all, in various ways, eat each other’. In his essay for the 1991 Yale Center for British Art catalogue, Mel Gooding wrote (p.9):

The Minotaur surprised looks directly into the eyes of the spectator. It is a look that disconcerts; we are confronted by a monster indeed, but human, all too (recognisably) human. Caught in this frightful act, it challenges us to pronounce it guilty of a sin to which it was predestined, to condemn it for conforming to its nature - our nature.

Hambling acknowledges that one of the problems of the painting was to make the head of the bull grow convincingly out of human shoulders. This area of the picture underwent a lot of work, and was made to look realistic by taking the colour of the human flesh up into the black hairy neck of the bull. Hambling wanted the Minotaur ‘to be very real and the space in which he stood to be endless, to recede into infinity’. An area of umber denotes the earth on which he stands and in the early stages of the painting the space around and behind the Minotaur was simply a field of raw sienna paint. In 1984 Hambling had begun a series of paintings and watercolours of sunrises, and the experience of a particularly striking London sunrise assisted with the resolution of the sky in T05023. She recalls that, having seen this sunrise one morning in December 1986, she applied a series of turquoise horizontal marks on to the existing field of raw sienna. These turquoise marks, mixed from viridian and white, related to ‘what was going on in the sky that particular morning’. T05023 is one of the two bull paintings in which the sky is ‘celebrated’ by being a positive element in the composition, the other being ‘Pasiphae and the Bull (Conception of the Minotaur)’, where ‘the sky is hot and fiery’.

One of the essays in Hambling's 1987 Serpentine Gallery exhibition catalogue was ‘Maggi Hambling's Minotaur Surprised while Eating’ by the art critic Peter Fuller. In this essay, Fuller compared her painting with another work in the Tate Gallery, ‘The Minotaur’, 1885, N01634, by the Victorian painter George Frederick Watts (1817–1904). Fuller wrote that ‘the resemblances between these two works may be more than a mere analogy’ (Serpentine Gallery exh. cat., 1987, p.25) and drew attention to the abstracted background common to both canvases. Watts's Minotaur faces away from the viewer and holds within his hand a small bird. Fuller stated that ‘Hambling confronts us with our brutish nature in a way more relentless than Watts would ever dared to have done’ (ibid., p.26). Hambling's Minotaur faces the viewer, with the result that ‘his back has been turned upon abstraction which can no longer provide a credible escape from our fallen condition in a seemingly godless world’ (ibid.). However, Hambling was unaware of the Watts painting before executing T05023.

In the mid-to late 1980s, Fuller promoted his theory that the British public live in an increasingly secular and godless age, and that the only road to spirituality and redemption was through art. He held strong views about the moral power of art, continuing the thesis that Ruskin had advanced during the second half of the nineteenth century. In 1988 Fuller founded and edited his own art magazine Modern Painters, a title taken from Ruskin, in which he wrote about a number of British artists, including Hambling, whose art he believed offered redemptive qualities. Peter Fuller discussed T05023 again in a televised debate with Matthew Collings on BBC2's ‘The Late Show’, broadcast on 19 October 1989. In support of their contrasting viewpoints on the identity of the most interesting contemporary artists, both critics were asked to select five works of art and to talk about each for one minute. The works were present in the studio. Collings selected works by Sigmar Polke, Simon Linke, Cady Noland, Martin Kippenberger and Art & Language. Besides T05023, Fuller chose works by Andrzej Jackowski, Arthur Boyd, John Bellany and William Tillyer. In the debate Hambling's painting was paired with a sculpture by Cady Noland, ‘Pipes in a Basket’. Fuller stated that T05023 was:

a picture which actually has the capacity still to shock us despite ... all the advertising imagery, all the kinds of things with which it has to contend ... The Minotaur is almost the opposite of the sort of Christ figure. The Minotaur is half-man, half-beast instead of half-man, half-god, and I think Maggi Hambling is trying to show us something about the bestiality of ourselves if you will, but ... she doesn't just show us something that is horrific. It's like having Francis Bacon and Rothko in the same painting, you see all these horrible scenes here but you have this beautiful strange, almost ethereal background and the two kind of clash and work against each other.

When asked about the possible influence on her work of Goya and of his scenes of bullfights, Hambling replied that when in 1977 she had originally visited Spain, she had looked at Goya's so-called ‘Black’ paintings in the Prado in Madrid. The one that she ‘felt most about’ was ‘Saturn Devouring his Children’, 1821–3 (repr. L'Opera pittorica completa di Goya, Milan 1974, col. pl.LVIII). This depicts the naked, kneeling body of a wild-eyed, long-haired man gripping tightly with both hands a small naked body, the bloody left arm of which he is about to bite off. Saturn was a Roman god, identified with the Greek god Kronos; personifying Time. He devoured all his children except Jupiter, the god of air, Neptune, the god of water, and Pluto, the guardian of the underworld, because these cannot be consumed by Time. When Hambling was asked to consider T05023 in the light of Goya's painting of Saturn she observed, ‘I wanted the place where the Minotaur is to be timeless’.

This entry has been approved by the artist.

Published in:

Tate Gallery: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions 1986-88, London 1996

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- landscape(1,191)

- eating and drinking(409)

-

- eating(230)

- classical myths: creatures(143)

-

- Minotaur(5)

- lifestyle and culture(10,247)

-

- cannibalism(6)

You might like

-

Jeffery Camp Rocket Over Venice

1986 -

Jeffery Camp Beachy Head: Brink

1975 -

Maggi Hambling Max Wall and his Image

1981 -

Maggi Hambling Mud Dream 1

1990 -

Maggi Hambling Mud Dream 3

1990 -

Maggi Hambling Mud Dream 6

1990 -

Maggi Hambling Sunrise 11.7.90

1990 -

Maggi Hambling Sunrise 14.8.88

1988 -

Maggi Hambling Sunrise 16.8.90

1990 -

Rita Donagh Counterpane

1987–8 -

Jeffery Camp Southcoast

1990 -

Maggi Hambling Portrait of Frances Rose

1973 -

Valerie Thornton Bominaco (The Abruzzi)

1988 -

Maggi Hambling Father, Late December 1997

1997 -

Maggi Hambling 2016

2016