In Tate Britain

- Artist

- Richard Hamilton 1922–2011

- Medium

- Oil paint, metal foil and digital print on wood

- Dimensions

- Unconfirmed: 1220 × 810 mm

frame: 1479 × 1074 × 67 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund and the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1995

- Reference

- T06950

Summary

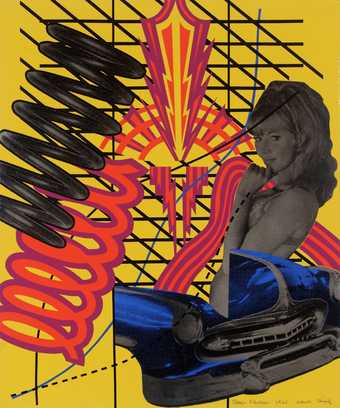

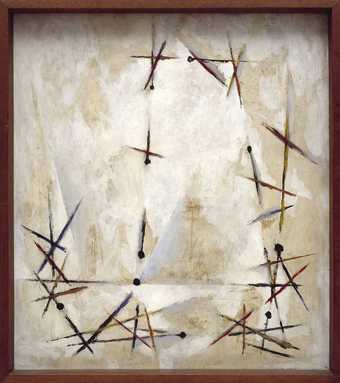

Hommage à Chrysler Corp. 1957 is an oil painting on a wooden support that depicts fragments of the bonnet of a car and the body of woman against a predominantly beige ground. The loose impression of the woman’s body leaning over the car is rendered only by patches of black and white paint that outline her curved form, by the pair of red lips, which identify the position of her head, and by a pattern of concentric circles, which appears to denote her left breast. While the bonnet’s overall shape is more clearly defined in pink and grey paint, a single headlight and the front bumper are the car’s only other easily identifiable features. A brown, egg-like shape appears to sit on the left of the bonnet. Much of the canvas is painted in a relatively uniform shade of beige, but there are some indications of an architectural setting, such as a darker rectangle on the left that might represent the edge of a wall.

This painting was made by the British artist Richard Hamilton in London in 1957. Hamilton has described it as a ‘compilation of themes derived from the glossies ... an anthology of presentation techniques’ (Hamilton 1982, p.31). It combines different stylistic methods gleaned from a number of magazine advertisements for General Motors, Chrysler and Imperial cars. The woman’s lips are modelled on the mouth of Voluptua, a character from late-night American television, and the shape of the breast is based on a diagram in an advert for an Exquisite Form Bra. The painting has changed in several ways since 1957. Pieces of metal foil were originally pasted onto it, but these are now missing. The brown-egg shaped form was produced in 2004 to replace an enlarged photograph of the air intake on a jet-propelled car, which Hamilton originally printed on thin photographic paper and stuck to the work. When Tate purchased the painting in 1995 this collage element had shrunk, become partially detached and had discoloured. In 1996 Hamilton decided that he wanted to replace the photograph and, after exploring various options, Tate conservation staff eventually produced the current image, which is based on a digital scan of the original collage element and printed on thin cigarette paper (see ‘Dilemmas in Contemporary Art: Richard Hamilton’s Hommage à Chrysler Corp. 1957’, http://www.tate.org.uk/about/projects/dilemmas-contemporary-art-richard-hamiltons-hommage-chrysler-corp-1957, accessed 8 September 2014).

In January 1957 Hamilton wrote a letter to the architects Peter and Alison Smithson, which provided the first ever definition of the term pop art. He wrote that pop art was ‘Popular (designed for a mass audience), Transient (short-term solution), Expendable (easily forgotten), Low cost, Mass produced, Young (aimed at youth), Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous, Big business’ (Hamilton 1982, p.28). Hommage à Chrysler Corp., which reflects the fusion of sexuality and the promise of speed in the marketing of American cars, was Hamilton’s first attempt to produce a work according to these criteria. Since the inception of pop art, critics have debated whether works such as Hommage à Chrysler Corp. were designed to celebrate or critique mass culture. But in the case of this work the art historian Hal Foster has refused such a simple dichotomy, arguing that ‘Hamilton is so affirmative of automobile imaging at mid-century, so mimetic of its moves, that he is led to ironize its fetishistic logic: to expose the break-up of each body on display … into sexy details whose production is obscure’ (Hal Foster, ‘On The First Pop Age’, New Left Review, no.19, January–February 2003, http://newleftreview.org/II/19/hal-foster-on-the-first-pop-age#_edn14, accessed 4 September 2014).

Hamilton’s deep engagement with industrial design – common to other members of the Independent Group of artists, writers and architects who met in London in the early 1950s – is reflected in this painting not only by the car, but by the evocation of an architectural space. The artist has stated that the painting includes a ‘token suggestion’ of the International Style of modern architecture, which became increasingly common in British cities after the Second World War (Hamilton 1982, p.32). The element referred to is likely to be the black band with straight edges and sharp corners that occupies the top-right corner.

The French title of the painting may allude to the influence of the artist Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), with whose work Hamilton was deeply engaged at the time he was making this painting. In 1957 Hamilton was in the process of translating Duchamp’s The Green Box 1934 (Tate T07744), a literary accompaniment to the French artist’s enigmatic painting on glass, The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) 1915–23 (Tate T02011), in which sexual bodies are represented as mechanical machines. The word ‘corps’ in the title is a double entendre signifying both a business corporation and a body (the French word for body is corps), the latter of which may refer to the body of a woman or that of a car. This multilingual word play prompts comparison with Duchamp’s famous use of visual and linguistic puns.

Further reading

Richard Hamilton, Collected Words 1953–1982, London and New York 1982, reproduced p.30.

Richard Hamilton, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1992, reproduced p.74.

Mark Godfrey, Paul Schimmel and Vicente Todoli (eds.), Richard Hamilton, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London 2014, reproduced p.77.

Judith Wilkinson

May 2014

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Online caption

This is one of a number of paintings by Hamilton that explore the relationship between women and cars, an association that has become an advertising cliché. He has removed and abstracted details so that the remaining areas appear as disconnected shapes and marks. A woman can be seen at the centre, leaning over a gleaming car. She is identifiable by her red lips and the shapes forming her breasts. These elements were derived from, or inspired by, adverts and popular imagery. Hamilton described the painting as a ‘compilation of themes derived from the glossies ... an anthology of presentation techniques’.

Explore

- objects(23,571)

-

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- underwear(73)

- mouth(238)

- lifestyle and culture(10,247)

-

- advertising(536)

- eroticism(409)

- car(502)

You might like

-

Peter Phillips Custom Print No. I

1965 -

Richard Hamilton Adonis in Y fronts

1963 -

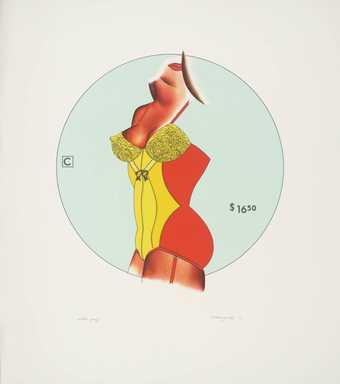

Allen Jones Three-in-One

1971 -

Richard Hamilton Fashion-plate

1969–70 -

Richard Hamilton Hers is a lush situation (1957)

1982 -

Richard Hamilton $he(1958)

1982 -

John Minton Composition: The Death of James Dean

1957 -

Antony Donaldson Take Five

1962 -

Richard Smith Vista

1963 -

Richard Hamilton $he

1958–61 -

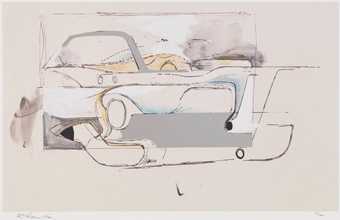

Richard Hamilton Trainsition IIII

1954 -

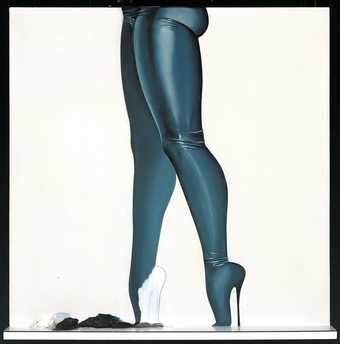

Allen Jones Wet Seal

1966 -

Richard Hamilton Chromatic spiral

1950