In Tate Britain

- Artist

- Dame Barbara Hepworth 1903–1975

- Medium

- Serravezza marble on marble base

- Dimensions

- Object: 210 × 532 × 343 mm, 23 kg

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by Mr and Mrs J.R. Marcus Brumwell 1964

- Reference

- T00696

Display caption

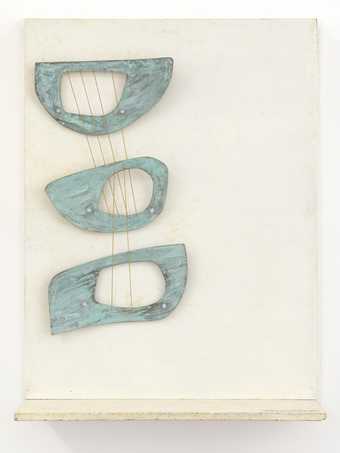

In 1934 Barbara Hepworth's abstraction

based on the human figure gave way to an art of pure form. With such works as Three Forms she reduced her sculpture

to the most simple shapes and eradicated almost all colour. She said later that she was 'absorbed in the relationships in space, in size and texture and weight,

as well as the tensions between forms'. While the three elements are slightly imperfect in shape, their sizes and the spaces between them are precisely proportional to each other. This reflects her concern with the craft of hand-carving and with harmonious arrangement

of form.

Gallery label, September 2004

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Dame Barbara Hepworth

1903-1975

T00696 Three Forms 1935

BH 72

Serravezza marble on marble base 200 x 533 x 343 (7 7/8 x 21 x 13 1/2)

Presented by Mr and Mrs J.R. Marcus Brumwell 1964

Provenance:

Purchased from the artist by Mr and Mrs J.R. Marcus Brumwell 1935

Exhibited:

14th 7 & 5 Society, Zwemmer Gallery, London, Oct. 1935 (no cat.)

Abstract & Concrete: An Exhibition of Abstract Painting and Sculpture, 1934 & 1935, 41 St Giles, Oxford, Feb. 1936 (13)

British Art and the Modern Movement 1930-40, Welsh Committee of the Arts Council, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, Oct.-Nov. 1962 (28)

Art in Britain 1930-40 Centred around Axis, Circle, Unit One, Marlborough Fine Art, London, March-April 1965 (40, repr. p.31)

Barbara Hepworth, Tate Gallery, London, April-May 1968 (26)

Henry Moore to Gilbert and George: Modern British Art from the Tate Gallery, Palais des Beaux Arts, Brussels, Sept.-Nov. 1973, as part of Europalia 73 Great Britain

(46, repr. p.61)

Art in One Year:1935, Tate Gallery display, London, Dec. 1977 - Feb. 1978 (no number)

Thirties: British Art and Design Before the War, Hayward Gallery, London, Oct. 1979-Jan. 1980 (6.61, repr. p.170)

British Sculpture in the Twentieth Century, Part 1: Image and Form 1901-50, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, Sept.-Nov. 1981 (166)

Barbara Hepworth: A Retrospective, Tate Gallery Liverpool, Sept.-Dec. 1994, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Feb.-April 1995, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, May-Aug. (20, repr. in col. p.63)

Un Siécle de Sculpture Anglaise, exh. cat., Galerie national du Jeu de Paume, Paris June-Sept. 1996 (no number, repr. in col. p.97)

Carving Mountains: Modern Stone Sculpture in England 1907-37, Kettle's Yard, Cambridge, March- April 1998, De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea, May-June (27, repr. p.29)

Literature:

William Gibson, Barbara Hepworth: Sculptress, London 1946, p.7, pl.26

J.P. Hodin, Barbara Hepworth, Neuchâtel and London 1961, pp.19, 163 no.72, repr.

Tate Gallery Report 1964-5, London 1966, p.39

'Recent Museum Acquisitions: Sculpture and Drawings by Barbara Hepworth (The Tate Gallery)', Burlington Magazine, vol.108, no.761, Aug. 1966, p.425, repr. p.424, pl.56

Ronald Alley, Barbara Hepworth, exh. cat., Tate Gallery, London 1968, p.13

Richard Morphet, Art in One Year:1935, display broadsheet, Tate Gallery, London 1977, [pp.3,4,5] repr. [p.5])

Dennis Farr, English Art 1870-1940, Oxford 1978, pp.290-1, pl.108a

Simon Wilson, British Art: From Holbein to the Present Day, London 1979, p.144, repr.

Charles Harrison, English Art and Modernism 1900-1939, London and Bloomington, Indiana 1981, p.269, rev. ed. London and New Haven 1994

David Fraser Jenkins, Barbara Hepworth: A Guide to the Tate Gallery Collection at London and St Ives, Cornwall, London 1982, p.10, repr. in col. p.25

Penelope Curtis, Modern British Sculpture from the Collection, Tate Gallery Liverpool 1988, p.51, repr.

Sally Festing, Barbara Hepworth: A Life of Forms, London 1995, pp.121,292

Penny Florence, 'Barbara Hepworth: the Odd Man Out Preliminary Thoughts about a Public Artist' in David Thistlewood (ed.), Barbara Hepworth Reconsidered, Liverpool 1996, p.28

Anne J. Barlow, 'Barbara Hepworth and Science' in Thistlewood 1996, p.100-1, repr.

Un Siécle de Sculpture Anglaise, exh. cat., Galerie national du Jeu de Paume, Paris 1996, p.458

Alan Wilkinson, Barbara Hepworth: Sculptures from the Estate, exh. cat., Wildenstein, New York 1996, p.21, repr.

Reproduced:

Herbert Read, Barbara Hepworth: Carvings and Drawings, London 1952, pl.37b

Jeremy Lewison, 'Aspects de l'art anglais dans les années trente', Années 30 en Europe: Le Temps menaçant 1929-1939, exh. cat. Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris 1997, p.82

Tripartite groups appeared in Barbara Hepworth's works with the advent of geometrical abstraction in 1935. Three Forms, 1935 is the largest and best known of these, and probably preceded by two others of the same moment, Two Forms and Sphere

(BH 63, private collection, repr. Hodin 1961, pl.63) and Three Forms (Carving in Grey Alabaster)

(Tate Gallery T03131). Both of the others have been placed in 1934 (Hodin 1961), but the sculptor's review of her work in December of that year makes this unlikely: 'It is 5 months or more since I did any' (postmarked 21 Dec. 1934, TGA 8717.1.1.197). Three Forms (Carving in Grey Alabaster)

featured in Henri Frankfort's article in July 1935 ('New Works by Barbara Hepworth', Axis, no.3, July 1935, p.16), where the absence of Three Forms, 1935 may suggest that it was not yet finished.

In retrospect, Hepworth placed the tripartite works immediately after the watershed in her sculpture caused by the birth of her triplets on 3 October 1934. In 1952, she recalled that her works had become 'more formal and all traces of naturalism had disappeared, and for some years I was absorbed in the relationships in space, in size and texture and weight, as well as in the tensions between the forms'. Perceiving the continuity with her subsequent work, she added an anthropomorphic reading: 'This formality initiated the exploration with which I have been preoccupied continuously since then, and in which I hope to discover some absolute essence in sculptural terms giving the quality of human relationships' (Read 1952, section 3). This was further qualified by the statement that 'the only fresh influence had been the arrival of the children' (ibid.). Ten years earlier, she had told E.H. Ramsden that Two Forms and Sphere

was the first work made after their birth (letter to E.H. Ramsden, 4 April 1943, TGA 9310); this seems to have been implied for each of the tripartite works, including Three Forms, 1935 (Tate Gallery Report 1964-5, 1966, p.39).

All three of these works display the concern with 'relationships in space, in size and texture and weight'. The rectangular bases define the relations between the three elements. The location of these was necessarily triangular, as Hepworth avoided a purely linear option, and the variations in size laid open potentially complex interrelations. In each case, a pair of forms - which in both Tate works included the largest - was ranged to the left and balanced by pushing the third far out (as if on a fulcrum) and activating the intervening space. The relative equality between the elements in Three Forms, 1935, means that this space is less exaggerated than in the related works, but, even so, the sphere is distinctly isolated.

The irregularity of the elements in each of these tripartite works was highlighted by the inclusion of a sphere. It acts as a compositional measure, matched against angular forms in Two Forms and Sphere

and against ovals in Three Forms (Carving in Grey Alabaster)

and Three Forms, 1935. It also sets up the proportional relationship with its more irregular fellows. The diameter of the sphere in Three Forms, 1935 is 120 mm (4 3/4 in.). This is the same as the depth of both the medium size element (85 x 180 x 120 mm; 3 3/8 x 7 1/8 x 4 3/4 in.) and the larger oval (180 x 255 x 120 mm; 7 1/16 x 10 x 4 3/4 in.); so that each is equivalent in this single dimension (in depth), variety being achieved in the other dimensions. Even there, the height of the large oval is equivalent to the length of the central element. Although the base has been replaced, the present spacing follows the original and is similarly regulated. This may be seen from the location of the largest element which is as far from the front of the base as the sphere is from the back (208 mm; 8 3/16 in.) - ensuring the open space on the right - and its distance from the right edge is equivalent to the length of the middle element (180 mm; 7 1/8 in.). This precision must be seen in the light of a significant adjustment - presumably made by Hepworth herself - to the position of the largest element: holes in the original base indicate that it was relocated about 10 mm (3/8 in.) further back. This alteration must have been of critical importance as it required drilling very close to the original holes and risked leaving the plugged holes visible. Shallow divots were taken out of the marble around the new holes in order to bed the element into the base; the same method has been used to locate the other two solids. Such 'spatial disposition' encouraged Frankfort to stress the role of the base in this group of works as 'by no means an accessory, but, on the contrary an essential part of the carving' ('New Works by Barbara Hepworth', Axis, no.3, July 1935, p.16).

The elements in Three Forms, 1935 are larger in relation to the base than in the associated works, and the rectangle is broader. The result is calmer than the frontal arrangement across the shallow stone of Three Forms (Carving in Grey Alabaster)

and more stable in the round. It is enhanced by the carving of all parts from the same white Serravezza marble, the luminosity of which lends a sense of permanence and classical form. It recalls Adrian Stokes's perception of the radiance of Hepworth's 'unstressed rounded shapes', and his definition that 'all successful sculpture in whatever material has borrowed a vital steadiness, a solid and vital repose' ('Art: Miss Hepworth's Carving', Spectator, 3 Nov.1933, p.621; reprinted in Lawrence Gowing, ed., The Critical Writings of Adrian Stokes, vol.1, 1930-37, 1978, p.309). The contemporary critical term 'vital' - even if usually gendered as Katy Deepwell has observed ('Hepworth and her Critics' in Thistlewood 1996, p.82) - signalled the ambition and achievement in Hepworth's work. In all these qualities, especially in the luminosity of the marble and the use of proportions, Three Forms, 1935 evokes a sense of classicism modified by modern vitality. It is in this respect that Frankfort could compare Hepworth's work to the Apollo of Olympia ('New Works by Barbara Hepworth', Axis, no.3, July 1935, p.16). Such comparisons reveal a fundamental departure from the primitivising references of the 1920s.

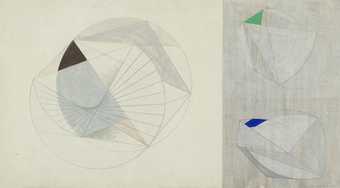

The degree of abstraction represented by Three Forms, 1935 is closely comparable to that in Ben Nicholson's white reliefs. Although the structure remained essentially pictorial, his adoption - under the influence of Hepworth's carving - of shallow relief at the end of 1933 went some way to meet her increasing definition of her work by the plane of the base. Their converging concerns were a function of their shared interests, contacts and work spaces in the Mall Studios. During 1933-4, Nicholson had the advantage of regular periods in Paris (seeing his first family) where he was in contact with the artists of Abstraction Creation alignment, of which the couple were members. Hepworth's pregnancy and the birth of the triplets severely limited the time she could dedicate to carving in 1934, although she later claimed that their arrival 'gave us an even greater unity of idea and aim' (Read 1952, section 3). Nevertheless, Three Forms, 1935 parallels such reliefs by Nicholson as the large mahogany 1935 (white relief)

(Tate Gallery T00049). There, the balancing of a compass-drawn and a hand-drawn circle exactly echoes Hepworth's combination of the sphere and the oval solids.

Among the members of Abstraction Creation, Hepworth's contributions of carvings contrasted with the enclosure of space by plane and line which typified the international constructivism of Naum Gabo, Antoine Pevsner, Alexander Calder and Katarzyna Kobro. In this respect, Hepworth maintained a latent relation to the techniques of Brancusi and (to a lesser extent) Arp, as well as to the direct carving ideals of the 1920s. The shift to abstraction expressed in her work, and that of Henry Moore, raised the question of reconciling a craft heritage with new forms. A.M. Hammacher has alighted upon this disparity exposed around 1936-7, commenting that while 'space became a point of departure' for Gabo's constructions and their carvings, 'neither Moore nor Hepworth found themselves able to relinquish their relationship with wood and stone, a relationship which had proved so fruitful' (A.M. Hammacher, Barbara Hepworth, 1968, rev. ed. 1987, p.74). The solution, exemplified by Three Forms, 1935 and by Moore's more organic Three-piece Carving, 1934 (destroyed, repr. David Sylvester, Henry Moore Complete Sculpture: Volume 1 Sculpture 1921-48, pp.38-9, LH 149), was the juxtaposition of abstract forms on a definite field. This seemed to owe something to Paul Nash's paintings of juxtaposed solids, and Three Forms, 1935 has been compared to Nash's Equivalents for the Megaliths, 1935 (Tate Gallery T01251) with its concentration upon illusionistic cylinders (Morphet 1977, [p.3]). Rather than the Surrealistic disjuncture taken up by Nash and Moore, Hepworth sought the contemporary 'equivalent' for pre-historic carving in geometrical solids, relying on the sphere in Three Forms, 1935 and related works such as Two Forms and Sphere, Two Segments and Sphere, 1935-6 (BH 79, private collection, repr. Hodin 1961, pl.79) and Conoid, Sphere and Hollow II, 1937 (BH 100, Government Art Collection, repr. Read 1952, pl.53). As well as the defiant balance, the attraction of the sphere lay in the same purity of form found in the circles of Nicholson's reliefs.

The works of Hepworth and Nicholson during this period are also united by the predominance of white, which achieved an ideological significance amongst modernists. It was a sign of the 'perfection, purity and certitude' of the era according to the Dutch constructivist Theo van Doesburg in Vers la Peinture Blanche

(Art Concret, April 1930, translated in Joost Baljeu, Theo van Doesburg, New York, 1974, p.183), a pamphlet which Nicholson may have been given by Hélion in late 1933 (Jeremy Lewison, Ben Nicholson, exh. cat., Tate Gallery 1994, p.44). In particular, the preference for white was associated with the clarity and proportional harmony of contemporary architecture, and especially that of Le Corbusier. In 1933, Jim Ede recommended that Hepworth and Nicholson visit 'La Roche in a Corbusier house in Paris' (letter to Nicholson postmarked 30 Mar 1933, TGA 8717.1.2.883) on their Easter holiday, presumably as much for the Cubist paintings as the building. At the same time, the architect Wells Coates - whom Hepworth and Nicholson knew through Unit One - was completing the modernist Isokon Flats in Lawn Road (1932-4) of which one was occupied by Adrian Stokes. In 1934, the presence of such modernist architecture in London was further reinforced by the arrival of Walter Gropius from the Bauhaus; Hepworth reported that Ben Nicholson's architect brother Christopher met him later that year (letter to Nicholson undated [Dec. 1934], TGA 8717.1.1.203).

However, in writing of the association of architecture with the use of white in Nicholson's reliefs, Charles Harrison has argued that 'the whiteness of the white reliefs should be perhaps taken as the distillation of a particular set of interests in the apperceptive world of painting, rather than as a reflection of an aspect of the history of design' (English Art and Modernism 1900-1939, 1981, p.264). Hepworth certainly shared the 'pursuit of an extreme clarity' which Harrison associates with Nicholson's memories of visiting 'the white-painted studios of Arp or Brancusi in 1932-3' (ibid.). For her part, Hepworth added a potent memory of Mondrian's studio which 'made me gasp with surprise at its beauty ... everything gleamed with whiteness' (Read 1952, section 3). She had also shared the important visits to the studios of Brancusi and Arp. A 'miraculous feeling of eternity' struck her in Brancusi's studio, where 'humanism ... seemed intrinsic in all the forms' (Read 1952, section 2). The immediate impact seems to have been exercised in Hepworth's organic abstractions of 1933-4 which drew upon Arp's work, but by 1935 she was responding to Brancusi's referential ovoid and oval forms by converting them into the more impassive abstraction of such works as Three Forms, 1935. Like Brancusi, Hepworth allowed herself greater variety in her choice of coloured materials than did Nicholson in his reliefs.

Three Forms, 1935 was conceived while Hepworth was a member of Abstraction Creation and came to represent an achievement of 'constructive' art. She was amongst those responsible for introducing it to Britain with the exhibitions of the 7&5 in 1935 and Abstract and Concrete Art

(1936) organised by Nicolete Gray; Three Forms, 1935 featured in both. The validity of constructive art raised considerable debate, and encouraged the editors of the 'survey' publication, Circle

(Gabo, Nicholson and the architect Leslie Martin), to solicit contributions from progressive scientists. The physicist Desmond Bernal was one of these and, in the same year, he wrote the foreword to Hepworth's exhibition (Lefevre Gallery, 1937), in which he drew attention to the 'surfaces of slightly varying positive curvature' and the exactitude of the 'placing and orientation' of forms. In an undated letter, perhaps in relation to these observations, Hepworth wrote to Bernal of the intuitive experience of the artist and defended constructive art as 'the one way of freeing every conceivable idea to its fullest intensity' (undated [1937-9], Bernal Archive, University of Cambridge, Add:8287/384). More specifically she added, with accompanying sketches of Three Forms, 1935: 'When you criticised my carving & said this was wrong [arrow to sphere] & should have been this [arrow to dotted-in cylinder] you were quite right, sculpturally, spatially & constructively'. Given her differentiation of the roles of artist and scientist, such an unequivocal acceptance of Bernal's sculptural judgement seems astonishing, but it may reflect a dissatisfaction with an earlier work (despite the proportional relationships it used) by comparison with the standards of her present work. So much is implied by her concluding remarks about the work:

if I solve the spatial form, ten to one I make a good carving, because I perfect the lines, form & tension & it lives. I might improve the one [form] you criticised, but my state of mind at the time I did it was not sufficiently clear, consequently the other 2 shapes have not the perfection that was required to solve the third shape.

It is interesting that the subject of this debate is the most superficially 'scientific' form - the sphere - which presumably lacked the surface variety that Bernal perceived in the sculptor's more recent elements. For her part, Hepworth accepted the application of 'laws' associated with constructive art, that a scientist could define and she could only grasp intuitively when her state of mind was - in language toned by her Christian Science beliefs - 'sufficiently clear'.

At the time of this debate, Three Forms, 1935 must already have been in the collection of Marcus and Irene Brumwell, friends and collectors of both Hepworth and Nicholson. Thirty years later, having donated the work to the Tate, Marcus Brumwell agreed that it was bought soon after being exhibited at the end of 1935, estimating: 'Shall we say 1 December 1935' (note to the Tate, March 1965, Tate Gallery Files). During that period it remained in remarkably good condition, limited to surface dirt.

However, on return from exhibition in Brussels in January 1974, the base was found to have been broken as the result of a 'sharp blow sustained unevenly' (Tate Gallery Conservation Files). The crack, which had chipped in the aperture, ran through one of the dowel holes for the medium size element and under the larger element. The impossibility of achieving a strong but invisible repair prompted the replacement of the original base with a new marble; this is slightly colder in colour. The iron dowels holding each form (three for the largest) were replaced with stainless steel as they had left rust marks, and the surface was cleaned and waxed (Tate Gallery Conservation Files).

Matthew Gale

April 1997

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- geometric(3,072)

- irregular forms(2,007)

- formal qualities(12,454)

You might like

-

Dame Barbara Hepworth Single Form (Eikon)

1937–8, cast 1963 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Forms in Echelon

1938 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Three Forms (Carving in Grey Alabaster)

1935 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Discs in Echelon

1935, cast 1959 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Poised Form

1951–2, reworked 1957 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Forms in Movement (Pavan)

1956–9, cast 1967 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Maquette, Three Forms in Echelon

1961 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Ball, Plane and Hole

1936 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Mother and Child

1934 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Drawing for ‘Sculpture with Colour’ (Forms with Colour)

1941 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Two Forms

1933 -

Paule Vézelay Five Forms

1935 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Pierced Hemisphere II

1937–8