On loan

Musée Granet (Aix-en-Provence, France): David Hockney

- Artist

- David Hockney born 1937

- Part of

- A Rake’s Progress

- Medium

- Etching and aquatint on paper

- Dimensions

- Image: 300 × 400 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1971

- Reference

- P07029

Catalogue entry

David Hockney born 1937

P07029-P07044 A Rake’s Progress 1961–63

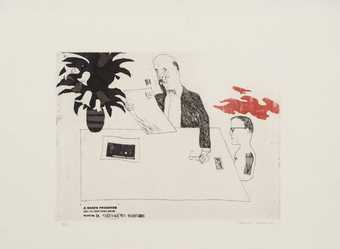

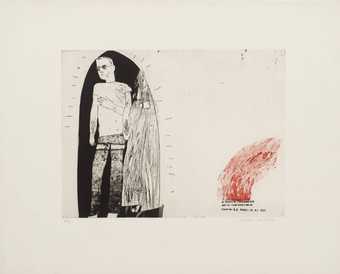

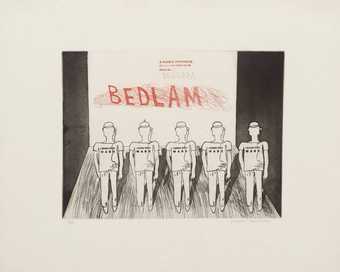

P07029 1. The Arrival

Title printed b.l.

Each print inscribed, just below plate, ‘20/50’ b.l., and ‘David Hockney’ b.r. Each print also inscribed on the plate, partly in etching and partly in aquatint, with a standard title for the suite, ‘A RAKE’S PROGRESS/ LONDON/NEW YORK 1961–62/PLATE NO.’, followed by the number and title of the individual print. The position of the title-inscription in each print is indicated above. Each print also embossed, b.r., with publisher’s device, ‘ea’.

Each print: Etching and aquatint printed in two colours, 11¿ x 15¾ (30 x 40), on sheet 19½ x 24½ (49.5 x 62).

Purchased from Kasmin Ltd. (Grant-in-Aid) 1972.

Lit: Robert Wraight, ‘Ilic, Haec, Hockney’, in The Taller, 18 December 1963; Wibke v. Bonin in cat., Galerie Mikro, Berlin, 1968; Mark Glazebrook in cat., Whitechapel Art Gallery, April-May 1970 (repr. p. 15).

Repr: Exhibition catalogue, Kestner-Gesellshaft, Hannover, May-June 1970 (15); Arts Review, October 1971, p.3 (plates 5, 6A, 7A, 8A).

Included with the suite are three further printed sheets—a title page, a page of technical information and an introductory statement by the artist inscribed ‘David Hockney 20/50’. The full title of the work, as given on the title page, is ‘A Rake’s Progress. A graphic tale comprising sixteen etchings 1961–1963’. It was printed by C. H. Welch, London, and published by Editions Alecto in association with the Royal College of Art, in December 1963. There were ten sets of artist’s proofs. The introductory statement by the artist reads: ‘These etchings were begun in London in September 1961 after a visit to the United States. My intention was to make eight plates, keeping the original titles but moving the setting to New York. The Royal College on seeing me start work were anxious to extend the series with the idea of incorporating the plates in a book of reproductions to be printed by the Lion and Unicorn Press. Accordingly I set out to make twenty-four plates but later reduced the total to sixteen retaining the numbering from one to eight and most of the titles in the original tale.

‘Altogether I made about thirty-five plates of which nineteen were abandoned so leaving these sixteen the published set. Nos. 7 and 7a were etched at the Pratt Graphic Workshop in New York City in May of this year, the others at the Royal College of Art from 1961 to 1963.’

The page of technical information accompanying the suite states that the Lion and Unicorn Press, Royal College of Art, was to publish a book of photolithographic reproductions of the etchings ‘in a subscribed edition of four hundred copies’. The Lion and Unicorn press published reduced-size halftone letterpress reproductions of the etchings in 1967, together with a poem commissioned for the volume by the Press, ‘A Rake’s Progress, a poem in five sections’ by David Posner.

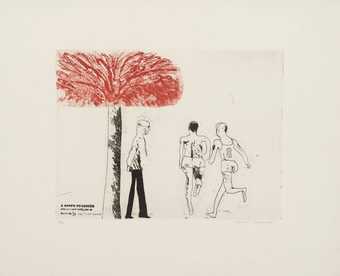

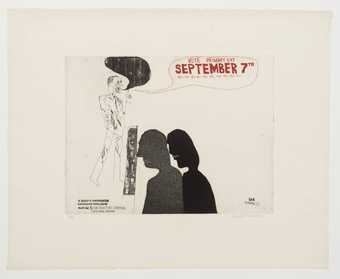

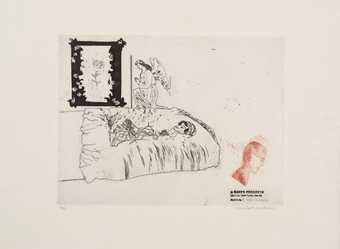

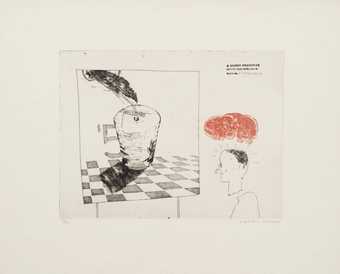

The model for Hockney’s work was Hogarth’s set of prints ‘A Rake’s Progress’, published in 1735; the subjects of Hogarth’s prints were (1) The Heir, (2) The Levée, (3) The Orgy, (4) The Arrest, (5) The Marriage, (6) The Gaming House, (7) The Prison, (8) The Madhouse. These themes are still found in Hockney’s work, but he titles them differently and they do not serve to illustrate a moral tale, that of a Rake’s downfall, but a social dilemma, the loss of individuality within a commercial society. He uses etchings to tell a story because he thinks that line can tell a story. He believes that the best etchings are linear in character. Wraight (op. cit.) has noticed that the drawing deliberately parallels the Rake’s decline. ‘A fresh and vital line for the arrival of the young man, a dull stodgy one for the final etching, when the hero has lost his individuality.’

The imagery of the prints derives from both literary and visual sources. Hockney had read both Walt Whitman and Theodore Dreisler before he went to America: many of Dreisler’s novels deal with the experience and subsequent moral corruption of young American men coming from the country into the social and financial world of American cities.

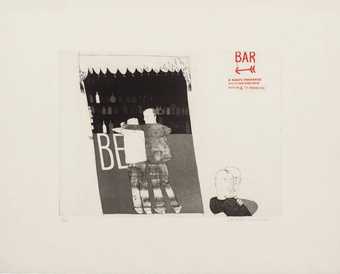

The visual influences on Hockney were of two kinds: that of artists, and that of popular advertising imagery. Amongst artists Hogarth determines the themes of the prints, although not the particular interpretations. William Blake’s influence is seen in plate 6A which is similar to a descent into Purgatory, or plate 7A. Hockney also greatly admired the contemporary artists Dubuffet, Francis Bacon and Ron Kitaj at this period. The advertising imagery and slogans appropriately register both what causes the downfall of the hero in America and the form that the downfall takes. Hockney includes in the prints references to advertisements, by which he himself was affected when he was in America; for example the letters on the bottle label in print 3 form part of the name ‘Lady Clairol’, a brand of hair dye, with which Hockney first bleached his own hair.

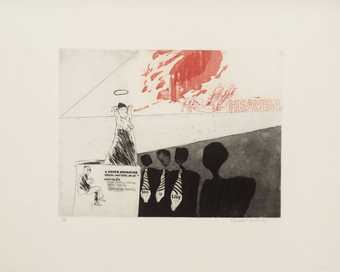

Although Hockney used the experiences and observations of his first journey to the States as the basis for the graphic tale, he disclaimed that the tale was autobiographical. ‘It is not really me. It’s just that I use myself as a model because I’m always around.’ The name ‘Flying Tiger’ on the plane in plate 1 was that of the charter company with which Hockney first flew to America in July 1961. The singer in print 2A is Mahalia Jackson whom Hockney heard for the first time in Madison Square Gardens, New York. He also met there the three men on whose ties the words of the inscription ‘ God is Love’ were separately written. Hockney says that he was particularly struck by the fact that in New York the bars and public houses were never shut; the scene of a typical American bar is depicted in plate 4, the ‘BE’ being part of the word ‘Beer’. The artist did not visit any gaol in the States; he said that it was sufficient (for plate 5A) to have seen Sing-Sing from outside. The hero is, in fact, looking at a prison scene in a cinema film; the man with numbers across his shirt is a seat attendant. The scene of plate 6, ‘Death in Harlem’, is based on a photograph by Cecil Beaton of the same title. The automaton-figures in plates 8 and 8A are carrying transistor radios in their pockets and are listening through earphones to the pop music played on the New York Radio station WABC. Hockney actually saw children like this in New York, and he said subsequently: ‘When I first saw them I thought they were hearing aids and was horrified at the amount of deafness among young people.’

Published in The Tate Gallery Report 1970–1972, London 1972.

Features

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

- townscapes / man-made features(21,603)

-

- tower block(152)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- gestural(763)

- literature (not Shakespeare)(2,276)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- suitcase(25)

- USA(622)

- lifestyle and culture(10,247)

-

- advertising(536)

- cultural identity(7,943)

- American(748)

- contemporary society(640)

- morality(57)

- inscriptions(6,664)

-

- word(280)

You might like

-

David Hockney 1a. Receiving the Inheritance

1961–3 -

David Hockney 2. Meeting the Good People (Washington)

1961–3 -

David Hockney 2a. The Gospel Singing (Good People) (Madison Square Garden)

1961–3 -

David Hockney 3. The Start of the Spending Spree and the Door Opening for a Blonde

1961–3 -

David Hockney 3a. The Seven Stone Weakling

1961–3 -

David Hockney 4. The Drinking Scene

1961–3 -

David Hockney 4a. Marries an Old Maid

1961–3 -

David Hockney 5. The Election Campaign (with Dark Message)

1961–3 -

David Hockney 5a. Viewing a Prison Scene

1961–3 -

David Hockney 6. Death in Harlem

1961–3 -

David Hockney 6a. The Wallet Begins to Empty

1961–3 -

David Hockney 7. Disintegration

1961–3 -

David Hockney 7a. Cast Aside

1961–3 -

David Hockney 8. Meeting the Other People

1961–3 -

David Hockney 8a. Bedlam

1961–3