Not on display

- Artist

- Claudette Johnson MBE born 1959

- Medium

- Pastel and gouache on paper

- Dimensions

- Support: 1515 × 1220 mm

frame: 1630 × 1320 × 50 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased using funds provided by the 2018 Frieze Tate Fund supported by Endeavor to benefit the Tate collection 2019

- Reference

- T15143

Summary

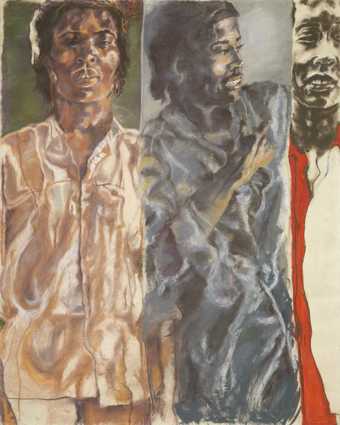

Standing Figure with African Masks 2018 is a monolithic drawing in pastel and gouache on paper of a female figure standing with her hands on her hips and her stomach exposed. Seen from a low viewpoint, she gazes directly down on the viewer, with a bold expression on her face. The figure’s skin and watch are rendered in dense pastel while her clothes – blue jeans, red shirt and black headscarf – are painted with loose brushstrokes of gouache paint with thick white inflections. Although not considered by the artist as a self-portrait, Standing Figure with African Masks is the first recognisable image that British artist Claudette Johnson has made of herself. It was drawn from life in the artist’s studio in East London, using a small mirror placed on a chair. The resulting vertiginous perspective heightens the confident stance held by the central character (indeed, the original title of the work was Brazen Woman). She is set against an abstract background of blue geometric forms outlined with yellow edges and is surrounded by three figures wearing African masks. These figures are rendered sparingly, with geometric lines and thin washes of brown paint, which cause them to recede into the background. They refer to Pablo Picasso’s (1881–1973) groundbreaking painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon of 1907 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), a painting that holds an important, if complicated, position in Johnson’s imaginary. She has explained:

I first saw Picasso’s Les Demoiselles D’Avignon (in reproduction) as a second year Fine Art student. I was struck by the rawness of the image, the fractured space, his use of African imagery and the fearlessness of the women. I referred to this work in And I have my own business 1982 (Museums Sheffield) in which a nappy headed woman with her arm raised and stomach thrust forward is bisected by a jagged yellow line. In Standing Figure with African Masks, the woman with her belly exposed directs her gaze out of the frame whilst being aware that she must negotiate a relationship with the African masked figures who are moving in from the periphery.

(Email correspondence with Tate curator Laura Castagnini, 6 November 2018.)

Through her citation of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Johnson creates a dialogue with the visual language of African masks as well as their appropriation by modernist Western artists and beyond. Standing Figure with African Masks is a monumental work that pays homage to the affirmative strength of self-representation by Black women in defiance of the colonial gaze. The artist has written: ‘I do believe that the fiction of “blackness” that is the legacy of colonialism can be interrupted by an encounter with the stories that we have to tell about ourselves.’ (In Hollybush Gardens 2016, p.6.)

Johnson has been making larger than life drawings of Black women since the early 1980s (see also Seated Figure I 2017, Tate T15262, and Figure in Raw Umber 2018, Tate T15261). Her figures are monolithic, seemingly to resist their containment within the edges of the paper. She usually works from life onto large sheets of paper taped to the studio wall. She begins with a dry pastel drawing, which she often paints over in sections using blocks of watercolour and gouache paint, before adding a final layer of drawing with pastel. The background, usually comprised of imagined and abstracted geometric forms, is created intuitively after the completion of the figure. The results are richly coloured and sensuous images that convey a sense of urgency in their expressive broken lines and pulsing forms.

Johnson describes her work as existing outside the realm of portraiture; rather she sees it as creating a ‘presence’ for her subject that resists objectification. She has written:

I am a Blackwoman and my work is concerned with making images of Blackwomen. Sounds simple enough – but I’m not interested in portraiture or its tradition. I’m interested in giving space to Blackwomen presence. A presence which has been distorted, hidden and denied. I’m interested in our humanity, our feelings and our politics; somethings [sic.] which have been neglected … I have a sense of urgency about our ‘apparent’ absence in a space we’ve inhabited for several centuries.

(Quoted in Claudette Johnson: Pushing Back the Boundaries, exhibition catalogue, Rochdale Art Gallery 1990, p.2.)

Johnson is motivated by an attempt to convey images of Black women without distortion or caricature, describing the difficulty of being ‘seen’. She is inspired by a generation of African American writers including James Baldwin, Toni Cade Bambara, Alice Walker and, most importantly Toni Morrison. In 2013 she stated: ‘From the moment that I read The Bluest Eye – Toni Morrison – I knew that I wanted to focus on black women as subject and form. In the novel Morrison writes about black people in a way that I could not recall ever having experienced before. It felt revelatory.’ (Quoted in Himid 2013, p.64.) She has often cited the treatment of Morrison’s central character Pecola, in particular her encounter with a white Southern shopkeeper, as a key source of inspiration because it illuminated ‘How impossible it was for a Southern shopkeeper to “see” her, yet how powerfully and accurately she could see him. How alive and vibrant she was inside and outside of the construct he had made of her.’ (Quoted in Claudette Johnson: Portraits from a Small Room, exhibition catalogue, 198 Gallery, London 1994, p.5.)

Johnson trained as an artist at Wolverhampton Polytechnic between 1979 and 1982 where she co-founded the Blk Art Group alongside artists Keith Piper, Eddie Chambers and Donald Rodney and, later, Marlene Smith. She played a key role in the formation of a Black British feminist art movement that developed in the 1980s, and participated in all three of the exhibitions curated by artist Lubaina Himid that have since defined the movement: Five Black Women at The Africa Centre and Black Woman Time Now at Battersea Arts Centre (both 1983), as well as The Thin Black Line at the Institute for Contemporary Arts in London (1985). Johnson has maintained a commitment to figuration throughout her career. In 2013 she said, ‘I felt that the figure could express everything; through figuration, abstraction and invention I could tell personal and in its widest sense political truths’ (quoted in Himid 2013, p.64).

Further reading

Lubaina Himid, Thin Black Line(s), exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2013.

Claudette Johnson, ‘Artist Statement’, in Carte de Visite, exhibition catalogue, Hollybush Gardens, London 2016.

Sonya Dyer, ‘Claudette Johnson’, frieze magazine, no.193, December 2017, https://frieze.com/article/claudette-johnson, accessed 15 October 2018.

Laura Castagnini

October 2018

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

To create this work Johnson drew herself using a small mirror on a low chair. She gazes directly down on us, at an angle that heightens her confident stance. She has said, ‘I’m interested in giving space to Blackwomen presence. A presence which has been distorted, hidden and denied.’ The masked figures in the background reclaim the often unacknowledged inspiration of African art on white Western artists. By referring to the masks as ‘African’, Johnson draws attention to art history’s failure to record the names, or even the nationalities of the artists of these influential works.

Gallery label, December 2020

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

You might like

-

Richard Wright Untitled Figure 2

2002 -

Richard Wright Untitled Figure 3

2002 -

Richard Wright Untitled Figure 4

2002 -

Richard Wright Untitled Figure 5

2002 -

Richard Wright Untitled Figure 6

2002 -

Richard Wright Untitled Figure 1

2001 -

Richard Wright Untitled Figure 3

2001 -

Richard Wright Untitled Figure 4

2001 -

Richard Wright Untitled Figure 5

2001 -

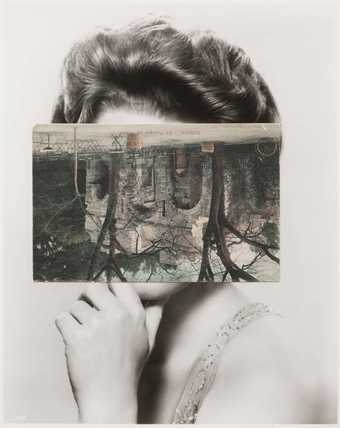

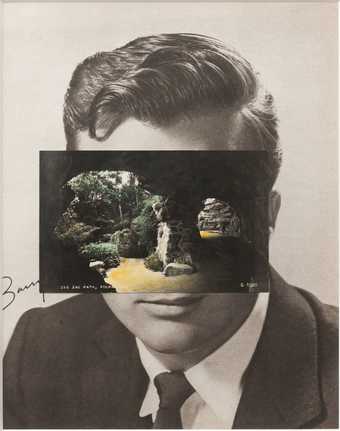

John Stezaker Mask XIII

2006 -

John Stezaker Mask XIV

2006 -

David Austen Woman Standing on Man’s Shoulders (Circus Act) 11.5.11

2011 -

Claudette Johnson MBE Figure in raw umber

2018 -

Claudette Johnson MBE Seated Figure 1

2017 -

Claudette Johnson MBE Untitled

1987