Not on display

- Artist

- Gulsun Karamustafa born 1946

- Medium

- Video, 2 projections, black and white and sound

- Dimensions

- Duration: 17min

Overall display dimensions variable - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by the Middle East North Africa Acquisitions Committee 2012

- Reference

- T13846

Summary

Memory of a Square is a double-screen projection video installation. One screen shows a series of eleven episodes narrating the history of a fictional family over three generations in their domestic environment. The second shows documentary film footage and photographs, taken from various sources between 1930 and 1980, of everyday and political activity in Taksim Square in central Istanbul. Although both are black and white the videos contrast in other ways, for instance the domestic scenes are filmed almost exclusively with a stationary camera, while the documentary footage uses numerous different camera angles as well as fading, panning and the super-imposition of images to move between different scenes. The soundtrack for each video combines classical piano with ambient background noise, including the intermittent sound of a crowd. The fictional narrative in the first video contains no dialogue, therefore the actions and emotions of the family are displayed though the actors’ gestures and expressions. Occasionally a photograph or image from the documentary footage appears in the domestic scene, indicating a correlation between the public and private events and linking the two videos together.

Memory, both individual and collective, is a central theme in Karamustafa’s work. It is understood by the artist as a flexible concept with which to mediate and interweave the history of Turkey with her personal biography. Between 1960 and 1980 Turkey underwent three military coups and a state of socio-political flux, which Karamustafa was an enforced witness to as she was prevented by the government from leaving the country from 1971 until 1986. Memory of a Square highlights the public and private aspects of these occurrences, with one video set in the public site of the square and another in the home. The different narratives and formal elements suggest the differences between historical record and personal experience, while the similarities and overlapping images reveal the impact of one on the other. The title of the work refers directly to the history of Taksim Square in Istanbul and its place in the history of the city as a meeting point for both daily life and political action. However, Karamustafa draws on the fact that the main square in many cities often becomes the focus of political demonstration and action and, despite the installation’s reference to Turkey, it could equally represent the history of countries such as Argentina, Spain, China or, more recently Egypt, which have undergone similar instances of political unrest. Karamustafa purposefully does not dictate a specific place or time for the domestic scenes, leaving it open to interpretation by the viewer (in conversation with Tate curator Kyla McDonald, April 2010). She avoids making direct statements about political events and has commented:

for me to be able to carry out my work, the subject has to be distilled; this is what protects me from giving direct messages, and from staying in the shallows. It took 27 years before one of my photographs related to the 1971 military coup could appear in a work of art: and it was only two years ago that the film ‘Memory of a Square’ had matured to my satisfaction after 10 years of consideration.

(Quoted in Heinrich 2007, p.7.)

After studying painting in Istanbul Karamustafa has, since 2000, worked primarily in video since, although continuing to create an extensive body of work in various media including textiles, painting, sculpture and installation. In Memory of a Square Karamustafa uses filmic techniques characteristic of her work – such as double screen projection, edited found footage and staged, near-theatrical settings – interspersing fictionalised narratives with historical events to create a non-narrative film that exposes the viewer to the subjective trauma of historical unrest.

Further reading

Barbara Heinrich, Gulsun Karamustafa: My Roses My Reveries, Istanbul 2007, pp.110–12.

Gulsun Karamustafa and Melih Fereli, ‘Interview with Melih Fereli’, in Barbara Heinrich, Gulsun Karamustafa: My Roses My Reveries, Istanbul 2007, pp.7–9.

Kyla McDonald

August 2011

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- architecture(30,960)

-

- townscapes / man-made features(21,603)

-

- square(473)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- memory(367)

- photographic(4,673)

- history(1,983)

- Japan(205)

You might like

-

Daido Moriyama Memory

2012 -

Daido Moriyama Memory

2012 -

Daido Moriyama Memory

2012 -

Daido Moriyama Memory

2012 -

Daido Moriyama Memory

2012 -

Daido Moriyama Memory

2012 -

Daido Moriyama Memory

2012 -

Daido Moriyama Memory

2012 -

Daido Moriyama Memory

2012 -

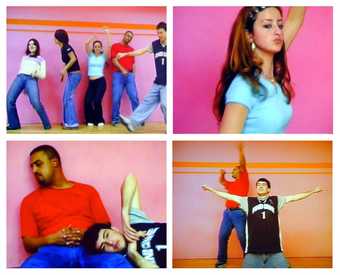

Fikret Atay Rebels of the Dance

2002 -

Phil Collins they shoot horses

2004 -

Apichatpong Weerasethakul Primitive

2009 -

Ellen Gallagher, Edgar Cleijne Murmur

2003–4 -

Sir John Akomfrah CBE The Unfinished Conversation

2012 -

Omer Fast The Casting

2007