Fig.1

Christine Eyene (left), Lubaina Himid (centre) and Dorothy Price (right) in discussion at the event ‘Lubaina Himid In Conversation’, Starr Auditorium, Tate Modern, London, 6 December 2021

Photo © Tate

‘Lubaina Himid In Conversation’ began with Christine Eyene stating the importance of non-linearity in Himid’s work, a topic that Dorothy Price had explored in a recent article in Art History.1 Himid offered: ‘I’m usually going forward and backward at the same time, but maybe I’m going inside and outside at the same time.’ While the conversation between Himid and Price barely moved past the first room of her Tate Modern exhibition, it teased out this dynamic spatio-temporal knot, its potentialities, and how artist, audience and critic alike are entangled within it.

Fig.2

Installation view of Lubaina Himid’s kangas hanging outside the entrance to the exhibition Lubaina Himid, Tate Modern, London, 2022

Photo © Tate

At the beginning of the exhibition, we encounter Himid’s kangas – colourful patterned fabric worn by East African women – that are placed outside the entrance to the gallery space (fig.2). This intentional placement circumvents the institutional and economic infrastructures of the museum by allowing a non-paying audience the chance to ‘see something for nothing’. Himid spoke of the loss that the positioning of these works attempts to make up for. She brought our attention to the children with ‘sticky fingers’ who have had access to the kangas under different conditions, and made it known that this access has not been completely denied. The kangas remain available for ‘very tall, very naughty, teenage boys’ who can reach them if they dare jump up. The evocation of these boys, whose subversive touch can, in a small way, make good on the potential of these objects to be transformed by the human body, appeared to be an invitation for that very touch – the planting of an idea, a subtle granting of permission.

Fig.3

Installation view of Lubaina Himid’s kangas hanging in the space outside the entrance to Lubaina Himid, Tate Modern, London, 2022

Photo © Tate

The kanga ordinarily consists of three parts: jina or methali (Swahili for message; often a riddle, an aphorism, a proverb or a joke), mji (motif; translated literally as ‘the town’ or ‘the womb’2 ) and pindo (border). These parts themselves speak to the constitutive elements of Himid’s spatio-temporal knotting and its technologies: language, container and boundary. The kanga is a two-dimensional cloth that is given new life in three dimensions when wrapped around the body, and in four dimensions as it joins its wearer in the art of living. The literal translation of mji as both womb and town – two spatial configurations at widely varying scales – is of particular significance. On Himid’s kangas, the womb/town offers us representations of insides. The bodily organs that appear as the mji of her kanga – heart, lungs, skin, eye and inner ear – all constitute the machinery that sustains life and makes available to our consciousness that which is outside of ourselves (fig.3). In referring to these in the discussion, Himid revealed a desire to speak to ‘the brutality of insight’. She described how these works were produced at a time when she was seeing and feeling different things than she had before and needed to find a way to link the two. She explained that the ‘installation is very much about you being inside the room as a kanga, the opportunity to be inside the kanga itself, wrapping it around you.’ I would argue that by also being part of this conversation, the audience became part of this wrapping, as the humour and irreverence which Himid extended to her works as she discussed them mirrored the qualities of jina.

Wrapping appeared in the various spatial configurations explored through the conversation. As both verb and noun, wrapping is processual; it can be partial, its form remade. As the social anthropologist Laurence Douny and the archaeologist Susanna Harris have observed, wrapping holds the possibility of unwrapping and to unwrap is not ‘simply to reverse wrapping; the act of unwrapping is significant in itself and has its own outcomes. Unwrapping may refer either to a physical or conceptual revelation, whereby knowledge is gained or secrecy exposed.’3 As a mode of clothing the human body, wrapping differs from tailored garments in its capacity to negotiate with the body. Wrapping can both shape and be shaped. Wrapping is an intentional act, and as Douny and Harris state, wrapping(s) are ‘put in contact with their contents and enable actions to be performed; they may also be perceived as boundaries to create interfaces between objects, subjects, and the world.’4 The possibility of remaking, of revelation, of the mutually constitutive nature of container and content, boundary and interface, reappeared in the conversation between Himid and Price at multiple scales. The borders of the kanga, the limits of the body, the spaces that enclose the body, clothing, architecture, and the territorial limits of land and sea, are all key boundaries and interfaces that are attended to. In response to an audience question about her use of colour, Himid referred to the significance of blue and its relationship to the sea. In doing so, she reminded us that spatial limits can also be temporal ones, as the sea could be understood as the ‘beginning of the end or the end of the beginning’ for those who were forced to cross it as part of the transatlantic trade of enslaved people during the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries.

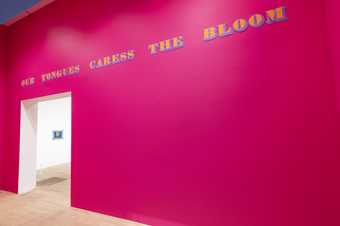

Fig.4

Installation view of the vestibule leading into Lubaina Himid, Tate Modern, London, 2022

Photo © Tate

It bears mentioning that the final kanga before entering the exhibition has as its mji a partial representation of the vestibular system, the inner ear organ involved in balance and spatial orientation. Its jina reads, ‘How do you spell change?’ (a quotation from the feminist activist and writer Audre Lorde) and speaks to the efficacy of language, the embodied and spatial nature of transformative potential, as well as the looping nature of listening.5 For Himid, ‘it’s about listening to yourself say that question’. Once we enter the exhibition, we come into a vestibule and in it we are wrapped inside the poet and activist Essex Hemphill’s words ‘Our kisses are petals, our tongues caress the bloom’, which are written in yellow and blue lettering high up on the wall (fig.4). This space was described by Price as ‘womb-like’, its deep fuchsia pink walls like the inside of something living. It offers the audience the experience of once again being ‘wrapped’ in a kind of safety before entering the parts of the show that for Himid ‘still feel dangerous’. Himid explained: ‘The letters then were painted in the particular colour they are and the walls the colour they are for that, again for you to be inside something and for something to be wrapped around you.’ Here, Hemphill’s words are the jina, the pink walls and lettering are the pindo, and the audience’s bodies are the mji. They are the wrapped and the wrapping, the vestibule acting on them such that they may become transformed and exit this space capable of transforming. Himid revealed that by placing Hemphill’s words so far above the audience, she intended to force a different kind of relationship with space and with the body: ‘if you are in an exhibition space and you’re already breathing and moving in a different way, then your body is telling you that something different may be possible.’ Himid wants us to know that we can encounter the world differently, and therefore that it is possible to shape it and rebuild it. And that others have done so in small and large ways.

Fig.5

Lubaina Himid

Three Architects 2019

Acrylic on canvas

1970 x 2710 mm

Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art at Rollins College, Rollins Museum of Art, Winter Park, Florida

© Lubaina Himid

As we move from the vestibule into the first main room in the exhibition, the audience is greeted with the sentence, ‘We live in clothes, we live in buildings – do they fit us?’. This prompt led the conversation to the painting Three Architects 2019 (fig.5), in which three Black women are shown standing in a room. Through the windows beyond them we see an endless watery horizon. Perhaps this room is in a vessel traversing a vast body of water. Colourful architectural models populate the space and the women are dressed in bright clothing. The green, yellow and blue of the central individual’s shirt is evocative of a silk dupion. They are unafraid of colour, as is common for Himid’s figures. In the discussion, this painting prompted reflections on how Himid’s figures negotiate their capacity to shape their built environment. Himid explained that the three architects’ approach to building is to ‘make it easy to escape’. In a world where we live in seemingly all-encompassing structures designed for us by others, these world-makers create buildings that we can dismantle and sail away in. Their spaces give dwellers control by being imbued with the possibility of altering their fit and of remaking them. The three architects, in their planning, strategising, detailing and working out of the ‘long view’, as Himid called it, are making in time as well as in space. These figures may be in tailored clothes rather than wrapped in kangas, but in their practice as makers they embody the processual nature of wrapping and its potential to shape and be shaped.

Fig.6

Audience view of Eyene (left), Himid (centre) and Price (right) in discussion at ‘Lubaina Himid In Conversation’, Tate Modern, December 2021

Photo © Tate

In its slow pacing, this conversation inadvertently highlighted the extent of Himid’s spatio-temporal extension from a single position. At one point, Eyene remarked that they had not gotten very far through the exhibition in their discussion. This speaks to Himid’s commitment to these ideas and what they make possible. It is due to her spatio-temporal reach and layered spatial consciousness, and the adroit manner in which these are given form, that the exhibition can be fully grasped by experiencing only its beginning.