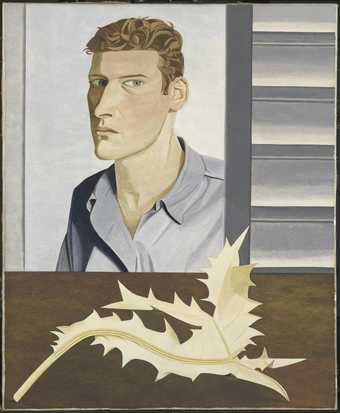

Lucian, My Father

Lucian Freud

Man with a Thistle (Self-Portrait)

(1946)

Tate

Man with a Thistle

‘I think my father may have got the idea for this melancholy self-portrait from Albrecht Dürer’s Portrait of the Artist with a Thistle, painted as a gift to his future wife, Agnes. During the 15th century, thistles were symbolic of a husband’s fidelity.’

When I was about 12 years old, my father phoned one evening to ask if I would come in a taxi with my sister Annabel to Bindy Lambton’s house on South Audley Street. I knew the house very well. It was a weeknight and I had homework, but my mother and Wynne, my stepfather, made no objection.

Bindy’s was a kind of second home to me. I was very close friends with Beatrix, Bindy’s secondeldest daughter. But more often than not, it was just me, Annabel, Bindy and Dad. They were lovers for many years.

I went there almost every Saturday to have lunch and spend the afternoon. After lunch we would frequently all pile onto Bindy’s bed and watch television. First it was Grandstand, while my father and Bindy placed bets on the horses. I always felt a thrill listening to the commentator summarising the form of each runner. Then there was the off, the fences, the winning post and the winner’s enclosure, as Dad and Bindy pored over the papers for the odds on the next race. That was followed by the wrestling – boring and embarrassing – and then the football results: Celtic, one; Rangers, one. Bournemouth, nil; Shrewsbury, nil. Sometimes we watched a film by the Marx Brothers or Bringing Up Baby with Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant. Juke Box Jury was the highlight of the afternoon.

Bindy seemed as impulsive, devil-may-care and dashing as Hepburn. I loved and admired her. She treated me as one of her own. She had collections of beautiful, enamelled boxes displayed on tiny glasstopped tables. She gave me a little porcelain box on which the words Within you see what pleases me painted on the lid and inside was a mirror. She gave me many presents, including a wonderful, electric racehorse that moved like a real horse, a clockwork tin bear that tossed a pancake in a frying pan, and a box of chocolates the size of a cartwheel.

Sometimes being alone with my father for the whole day could be a strain, particularly if something was bothering him. Being with my him and Bindy as a couple meant that I could just relax and not have to talk about my life at home with my mother and Wynne, or think of things to say.

Otherwise, we went to the zoo, the National Gallery, or the cartoons at the news theatre, sometimes to his studio on Delamere Terrace. Bindy provided a loving and maternal environment. She had the measure of my father and seemed somehow to know how to tame him. He admired her abundant physicality: painting her gave him fantastic opportunities.

That night we arrived at South Audley Street to find John Aspinall, the gambling club owner, in the dining room with two of his tiger kittens. Except that they were not kittens. They were as tall as I was, savage and playful with terrifying eyes, sharp teeth and claws, and kept bounding up on their hind legs to put their paws on my shoulders. John Aspinall was Birth Control for my father ‘This really ought to be simply the most marvelous thing, but aren’t words strange? Birth after all, what could be better than the beginning of a life? And control, necessary for everything that life has to offer and incidentally one of my favourite things’ chortling to my father about his breeding gorillas: ‘Twenty-eight copulations a day!’ I heard him say.

The next day, when we came home from school, my mother wrote a letter to Annabel’s teacher to say that she was not making up a story and had spent the evening playing with real baby tigers.

Lucian Freud with his daughter Annie in 1950, photographed by Cecil Beaton

© The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive

This poem, Birth Control, records something my father once said to me.

Birth Control

for my father‘This really ought to be simply the most marvelous thing, but aren’t words strange?

Birth after all, what could be better than the beginning of a life?

And control, necessary for everything that life has to offer and incidentally one of my favourite things’

Kitty, My Mother

Girl with a Kitten

‘One of the many striking things about this painting of my mother is the manner in which she is holding the kitten. It is held up in the way a person might hold a hand mirror, except that the kitten faces outwards, as if to say: this is you. It communicates an unfathomable logic.’

My mother’s relationships with her favourite authors were always so personal that they seemed her closest and most reliable friends. Some of them, she fell out with. Colette, whom she had adored, was suddenly too self-regarding, D.H.Lawrence too given to exaggeration, and Austen and Brookner, too cruel. Other favourites were Rumer Godden, Elizabeth Goudge’s Island Magic and Angela Thirkell’s Before Lunch, read and reread many times.

Kitty Garman with her daughter Annie in 1948

Courtesy Annie Freud

Until her very last years she was always rereading Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu. Her devotion to him was total. It felt like a very private relationship, something to be mentioned, but not shared. Kierkegaard, she regarded as the master and source of all wisdom. And always Shakespeare, the source of a different kind of wisdom. I used an extract from one of her letters to me to write this poem:

O, These Men, These Men

Cloyed and sickened by Colette’s crude rusticities – Too many teats & nipples, too much self-praise – I turned to Shakespeare last night – the heart-breaking scene in Othello, where Desdemona is having a goodnight talk with her worldly-wise companion. She sings her song about the Willow and the Forsaken Maid, and bursts out: O, these men, these men. I felt it was the cry of all women all over the world in their mystification at this other sex who behave so inexplicably, yet somehow are so necessary, unwieldy as they may be.

Emilia’s response is so sensible and comforting – & reminds her mistress that women can be as lustful, fickle and perverse, & that perhaps it may all be a game.

Was in floods myself & went to bed, having made myself a rather nasty omelette, eggs being the only provender in the house.

My mother’s favourite poets were Cowper, Keats, Rossetti, Verlaine, Rilke, Larkin, Edward Thomas, Ratushinskaya and Cope. The writer she most revered was Henry James. His intuition as regards the dilemmas of his women characters were an endless source of fascination and sympathy. She collected his books, and books about him. I have them and treasure them all, as I treasure my many memories of her.

Lucian Freud: Real Lives, Tate Liverpool, 24 July 2021 – 16 January 2022. Curated by Laura Bruni, Assistant Curator, Tate Liverpool. Supported by Tate Liverpool Patrons.

Annie Freud is a poet and artist living in Dorset