The Milanese art specialist Ambrogio Ceroni published three volumes on the work of Amedeo Modigliani, in 1958, 1965 and 1970. While the first two volumes established Ceroni’s name as a Modigliani expert, the third, which covers some 337 paintings and twenty-five sculptures, has become the most widely valued reference work on the artist. Ceroni’s volumes differed from those by other authors in that they sought to provide an art historical and documented analysis of the painter’s works.1

The first of Ceroni’s publications contains a brief introduction followed by five previously unpublished letters, dating from 1901 to 1905, that Modigliani sent to his friend, the painter Oscar Ghiglia, together with the unpublished ‘Souvenirs’ of the Polish exile Lunia Czechowska, whom Modigliani painted on numerous occasions.2 The volume comprises a condensed biography, a list of solo and group exhibitions organised between 1908 and 1958, and a comprehensive bibliography. In the second volume, from 1965, a brief introduction explains the expanded structure of the publication and Ceroni’s rationale for his selection of drawings and sculptures and the addenda to his earlier 1958 list of paintings.3 It also includes a selection of drawings from the collections of Sydney G. Biddle and Paul Alexandre. Historical context is provided by the re-publication of the critic Waldemar George’s text on an exhibition of Modigliani’s paintings held at Galerie Bing, Paris in 1925, together with four installation photographs of the show.

Ceroni’s decision to increase his catalogue of paintings to 222 works in the 1965 volume, adding sixty-six new works, was informed by the numerous exhibitions devoted to Modigliani between 1958 and 1963, through which many previously unknown or lost works came to light. Ceroni included a statement that his research had identified at least 160 indisputable fakes and another twenty questionable works, of which he had assembled black and white images, but which he would not reproduce. The 1965 volume concludes with images of the 222 works catalogued, reproduced one per page. Ceroni’s third book on Modigliani was published in May 1970, as no.40 in Rizzoli’s Classici dell’arte series, a popular, low-cost, weekly publication available in newspaper kiosks across Italy.4 The section devoted to the catalogued paintings is presented chronologically as a series of small images in black and white, which, with its almost cinematographic sequencing, has proven extremely instructive for later scholars. This main section is followed by an appendix that reproduces twelve drawings relating to the twenty-five sculptures included in Ceroni’s 1965 volume.

The 1970 catalogue, despite its high print run, wide distribution and low price, represents the culmination of Ceroni’s studies dedicated to Modigliani. It has become the most frequently consulted Ceroni publication and an essential point of reference for subsequent catalogues of Modigliani’s paintings. Ceroni himself did not consider this publication to be a definitive catalogue raisonné of Modigliani’s paintings.5 However, despite some errors in dating, titles and medium, it remains the most reliable catalogue and the only one currently recognised by major auction houses. Ceroni’s research methods were primarily art historical and related to provenance; he did not physically examine some of the works nor did he have access to the imaging or analytical equipment available today.

Two paintings now held in major museums – Madame Zborowska 1918 in the Tate collection and Portrait of a Student (L’Etudiant) c.1918–19 from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York – were not included in Ceroni’s 1970 publication. There are a number of possible reasons for this. It is likely that the author did not have access to the portrait of Madame Zborowska at the time of writing, as it was in a private collection in the United Kingdom. Anna Ceroni, the art historian and daughter of Ambrogio Ceroni, has confirmed that she has found no references to the painting in her father’s archive.6 If he did see it, it is possible that there were aspects of the appearance and technique that did not fit with other known works, both of this date and this subject. Although Ceroni did have an image of Portrait of a Student in his archive, it is doubtful that he saw the painting in person, and may not have felt the work strong enough to include it based on a photograph alone.7 In our attempt to understand more about Modigliani’s working practice and why these two paintings may not have been included in the Ceroni publication, we decided to examine both works to see if they differ in appearance, technique or material composition from contemporary works that were documented in Modigliani’s lifetime. By viewing images taken with infrared radiation and X-radiography, information is gleaned regarding underlying drawing or painting, compositional changes and brushwork. Using extensive research into other known works, these aspects of the paintings are assessed as to whether they align with what has been observed in other paintings by Modigliani. Pigment and binder analysis aids in determining if the materials were available during the period, or if the palette and medium are consistent with other works in the artist’s oeuvre.

Madame Zborowska and her relationship to Modigliani

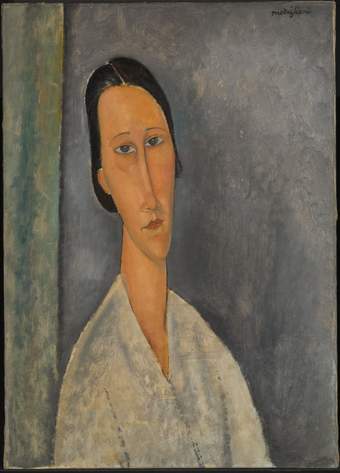

Fig.1

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska 1918

Oil on canvas

645 x 450 mm

Tate

The painting analysed from the Tate collection, Madame Zborowska, is a portrait of Anna Zborowska, also known as ‘Hanka’ (fig.1). She was the common-law wife of Léopold Zborowski, who had been Modigliani’s dealer and friend since 1916. There are at least twelve portraits of Anna Zborowska included in Ceroni’s volume of 1970, but this is one of a handful that is not in the publication, despite having a provenance that goes back to the late 1920s.

Anna Zborowska, née Sierzpowska, was the daughter of Maurice Sierzpowski and Josephine Jaczewska, who both died when she was a child. Anna and her sister Zofia were brought up by their maternal uncle Kazimierz Jaczewski in the Polish city of Lublin. In 1910 Anna and Zofia emigrated from Poland to Paris, where in August 1914 Anna met Léopold Zborowski in the Café de la Rotonde. Although they never married, Anna was known as ‘Madame Zborowska’ and posed regularly for Modigliani.8 By the time of the First World War, which started in 1914, Modigliani was almost destitute, but from 1916 Zborowski supported him with a modest stipend and art supplies, sometimes providing him with a place to work and models to paint.9 Zborowski was among the first to champion the artist and in 1917 he co-organised the only solo exhibition of Modigliani’s work to be held in the artist’s lifetime, with the gallery owner Berthe Weill.10 He also guaranteed Modigliani’s extensive presence in the Exhibition of French Art 1914–1919 held at Heal’s Mansard Gallery, London in 1919, an exhibition that secured the artist’s reputation outside France.11 When Modigliani fell ill in 1919, it was Zborowska who is said to have nursed him. As Modigliani’s partner, Jeanne Hébuterne, died only days after the artist, and since Modigliani’s own family were far away in Italy, it fell largely to Zborowski to manage his estate and legacy after his death.

Madame Zborowska is thought to date from 1918, the year in which Modigliani, at the behest of Zborowski, left Paris for the South of France to seek refuge from the uncertainties of the First World War. It is likely that Zborowski wanted to protect the ailing Modigliani and safeguard his investment in the artist.12 Zborowska accompanied the party to the South of France for the final months of the war and it is possible that the painting was made at this time. Modigliani had limited access to models there and used friends and family as well as local children as sitters for his portraits. He also painted a few landscapes, but was not confident in the genre, describing his efforts as those of a beginner.13 During this period in le Midi, Modigliani’s earlier textured surfaces and dark grounds were abandoned for a more luminous palette. The pale colours and the thinly applied paint on a white ground of Madame Zborowska appear similar to those of the paintings that Modigliani produced in Cagnes and Nice.

The provenance of Madame Zborowska is traceable to Zborowski, who owned the picture in the 1920s.14 It subsequently belonged to two collectors based in Paris: Modigliani’s early patron Jonas Netter and the framer and dealer Constant Leonard Lepoutre.15 The portrait’s dates of ownership are not clear and it may be that Lepoutre had it first, and then sold it to Netter.16 The painting was included in the 1929 catalogue raisonné by Arthur Pfannstiel and in the later catalogue raisonné by J. Lanthemann in 1970.17 Art historians Simonetta Fraquelli and Anna Ceroni note that Zborowski and Netter had much to gain by the publication of Pfannstiel’s 1929 catalogue.18 Zborowski had set up his own gallery in 1926 and was keen to augment the value of Modigliani’s work, while Netter possessed at least twenty-eight works by the artist and sold several more. Indeed, having already begun in 1916 to acquire Modigliani’s paintings, in 1919 Netter was formally contracted to share with Zborowski his choice of one half of Modigliani’s production, some of which he would sell on.19 Netter made further sales after the publication of Pfannstiel’s catalogue, on the occasion of the Venice Biennale of 1930, and out of important monographic exhibitions in Brussels and Basel in 1934.20

Technical analysis of Madame Zborowska

Madame Zborowska is painted on canvas. Microscopy indicates that the canvas is made of linen with an unusually open, plain weave. Thread counting software applied to a high-resolution X-radiograph indicates that the warp direction is horizontal, and that the threads have an average density of 18.6 warp threads per centimetre with small variation, and 17.2 weft threads per centimetre, with more variation in the weft density, which is commonly found in canvases.21 Research carried out by Don Johnson and the Thread Count Automation Project has identified this canvas as belonging to a cluster of paintings cut from the same roll of fabric. These include Standing Nude (Elvira) 1918 in the Kunstmuseum, Bern (C272), Madame Survage 1918 in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nancy, Nancy (C277), Girl with a Polka Dot Blouse 1919 in the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia (C298) and Jeanne Hébuterne Seated 1918 in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem (C329).22

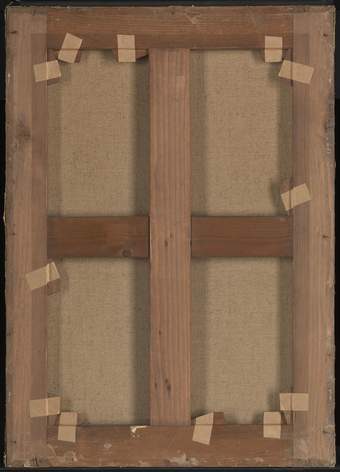

Fig.2

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, reverse showing the non-original stretcher and the canvas lining, with its edges cut to align with the sides of the stretcher

Photo: Tate Photography

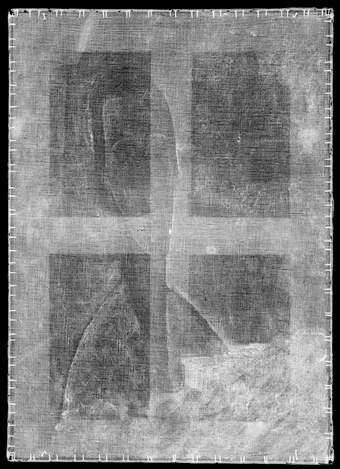

Fig.3

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, X-radiograph showing double tacks around the outside edges

Photo: Tate Photography

Neither the X-radiograph nor the thread counting give clear indications of cusping – distortion of the canvas weave resulting from the stretching of the canvas – related to the original stretcher. The canvas was lined with glue paste and attached to a non-original stretcher prior to its arrival at Tate, giving it the dimensions of 64.5 by 46 cm (fig.2). This corresponds most closely to size 15 paysage bas format (65 by 45.9 cm). There is no record of the original stretcher or strainer. The paysage bas format stretcher is inverted to stand on its short end and it is perhaps noteworthy that the original format was designed for landscapes, whereas Modigliani tended to favour marine formats for his South of France portraits. Turning the canvas with the longest sides in the vertical orientation would have helped create the elongated aspect of the portrait. Interestingly, when the canvas was attached to the existing stretcher, the wooden stretcher already had tacks in the edges, indicated by the fact that double the number of tacks is visible in the X-radiograph than can be seen on the outside of the tacking margins (fig.3). It is not known when and why the painting was lined and re-stretched; it may have been expedient to leave the tacks in place rather than to painstakingly remove them. It does, however, suggest the use of a second-hand stretcher rather than a new one.

The X-radiograph shows that there are blank, unpainted spaces (reserves) left around the sloping shoulders of Zborowska, where they appear as black lines, as there is little or no paint. The face shows similar dark, transparent contours, but there is also a build-up of thicker paint around the face, creating a white halo, particularly on the right-hand side (see fig.3). The features of the face are difficult to discern in the X-radiograph. There are two sweeping diagonal lines across the centre of the image, which may be a result of the application of the ground or perhaps related to a design beneath the portrait.

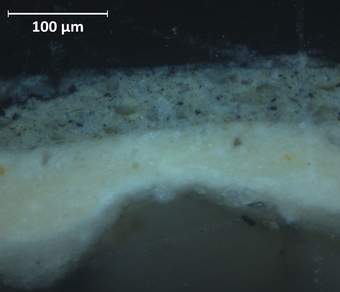

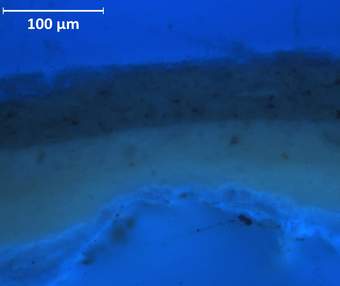

Fig.4a

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, cross-section (s6x320 vis) showing the paint for the curtain at the left edge in visible light

Photo: Joyce Townsend

Fig.4b

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, cross-section (s6x320 uvf) showing the paint for the curtain at the left edge in ultraviolet light

Photo: Joyce Townsend

The canvas was pre-primed with thinly applied, off-white commercial priming made of lead white, some chalk and a trace of barium sulphate extender (fig.4a). The priming was applied over a very thick, probably cold, size layer that included some chalk. This provided, in effect, a double preparation with a semi-transparent lower layer followed by a more opaque off-white layer that would absorb some medium from the paint applied to it (fig.4b). This is similar to the preparation of the canvas for Standing Nude (Elvira).23

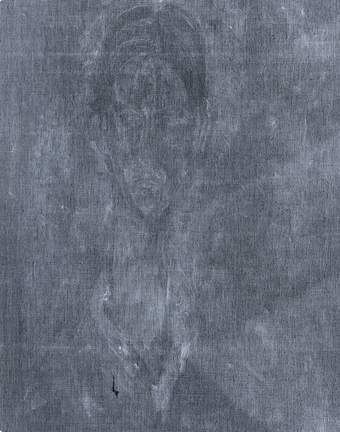

Fig.5

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, infrared reflectogram

Photo: Aviva Burnstock and Silvia Amato, Courtauld Institute of Art

Fig.6

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, infrared reflectogram, detail of the centre of the painting turned 180 degrees

Photo: Aviva Burnstock and Silvia Amato, Courtauld Institute of Art

Fig.7

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, infrared reflectogram, detail possibly showing a flat roof with a tower at the centre of the painting

Photo: Aviva Burnstock and Silvia Amato, Courtauld Institute of Art

Fig.8

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, detail of the surface, possibly showing a drawing of a flat roof and tower with some pink paint filling in the flat roof

Photo: Annette King

Fig.9

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, detail of the texture of the painted rooftop showing through the surface

Photo: Annette King

Fig.10

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, adjusted infrared reflectogram detail of outlines, possibly houses, at the right edge of the painting, turned 180 degrees

Photo: Aviva Burnstock and Silvia Amato, Courtauld Institute of Art

Fig.11a

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, detail of the face in normal light

Photo: Tate Photography

Fig.11b

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, infrared reflectogram detail of the face showing pencil lines unrelated to the final composition

Photo: Tate Photography

Fig.12

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, infrared reflectogram detail of spiky pencil lines in the lower left corner of the canvas, turned 180 degrees

Photo: Aviva Burnstock and Silvia Amato, Courtauld Institute of Art

The infrared reflectogram (IRR) for this painting reveals an unrelated drawing in the central region of the painting, which is still evident through the thinly painted surface of the work (fig.5). The lines form geometric shapes across the horizontal plane. When the canvas is turned upside down, the lines cohere into what appears to be a series of houses or a village in a landscape (fig.6). It is thus possible that the canvas began life as an unfinished landscape. The shapes of the ‘houses’ and the ‘village’ on an incline were possibly drawn in pencil, and the central shape, which could be a flat roof with a tower, was painted with a pinkish colour for the tiles (figs.7–10). There is no direct equivalent to these shapes in the few existing landscapes by Modigliani, but there are similarities in the shape of the buildings and the way they intersect and overlap at unusual angles with the forms in his Landscape at Cagnes 1919 (private collection; C292).24 There are some curved pencil lines beneath the paint of the nose (figs.11a–b), which are unrelated to the upper painting and may be initial outlines of trees or foliage. There are also some spiky pencil lines in the lower left of the torso that do not appear to relate to the figure painting (fig.12). Straight lines can be seen in the chin, mouth and proper right cheek; these may also be part of the initial architectural scheme. Modigliani only painted four known landscapes, all of which were on paysage formats in the vertical orientation, enhancing the impression of the vertiginous hillsides of the South of France.25 The choice of paysage bas for this painting perhaps strengthens the idea that it began as a landscape, which was later abandoned.

The drawn outlines of the face and shoulders of Madame Zborowska are more or less completely concealed by painted black lines in the upper layers, which makes any initial sketch for the figure difficult to evaluate. If they exist, the sketched lines have been followed faithfully in the painting phase and used to define the outlines of the face. The hair is a purplish-red tone of black that would conceal any underdrawing. Drawing lines can be observed in the IRR image (see fig.5), especially in the outline of the lower face and the neckline.26 Hard graphite pencil seems the most likely material for such fine lines, applied with no wavering and in a continuous line for each form. The curtain to the left of the sitter is not drawn but executed entirely in paint.

Fig.13

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, X-radiograph, detail of the lower right corner turned 180 degrees, showing lead white-based paint following a distinct contour

Photo: Tate Photography

The X-radiograph shows a very thinly painted canvas, with the exception of the lower right corner, which has a denser area of paint containing some lead white, a pigment that is rendered more clearly in the X-radiograph. The lively brushwork does not seem to be concealing anything. The colour beneath the upper image in this corner is pale blue and the contour of the sketchy lead white-containing paint seems to follow a distinct shape (fig.13). When turned upside down, it is possible to surmise that this was intended to be a stretch of sky in a landscape, following the contour of buildings. If so, this composition was abandoned at a relatively early stage, the canvas rotated and the painting continued as a portrait of Zborowska.

Fig.14

Amedeo Modigliani

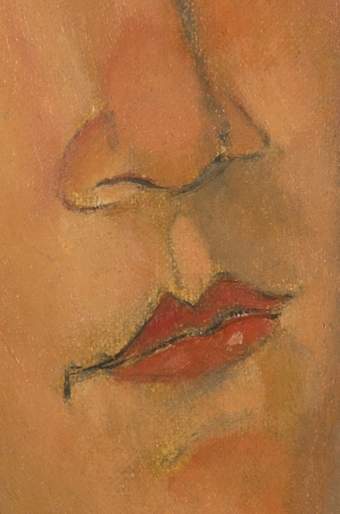

Madame Zborowska, detail of the flesh, nose and lips

Photo: Tate Photography

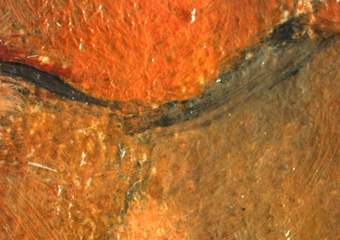

Fig.15a

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, photomicrograph of the centre of the nostrils

Photo: Joyce Townsend

Fig.15b

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, photomicrograph of the proper right nostril

Photo: Joyce Townsend

The surface of the sitter’s flesh has a very matte appearance under magnification (fig.14). The paint was first applied within the underdrawing with very little modulation of tone in a cooler and more yellow colour than in the upper layers, leaving narrow borders of non-painted priming. A second paint layer in warmer tones modelled the features and narrowed the unpainted margin of white priming, for example at the tip of the chin. The visible brush marks on the flesh suggest a fast-drying medium, as the paint dried before it had time to level. Details of the face were further modulated by grey shadows and outlines. The long dark line that runs down the side of the nose to the nostril was painted in smoky grey on white ground left exposed by a gap in the flesh paint. The nostrils were modelled in a pale flesh tone, with grey shadows, touches of warm pink that extend over the grey lines, and pure dark red pigment, which outlines the nostril on the proper right (figs.15a–b).

Fig.16

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, photomicrograph of the lips

Photo: Joyce Townsend

The red lips were painted over the pale flesh colour and outlined in black (fig.16). It seems that the red overlaps the black lines in places along the edge of the mouth, but the central black line was applied over the red as a final touch. There is a realistic highlight on the lower lip. The area between the nose and the mouth is modelled in darker flesh tones and grey shadows, with a touch of light pink in the philtrum and just below the lips. The upper lip appears to be a slightly darker shade of red than the lower.

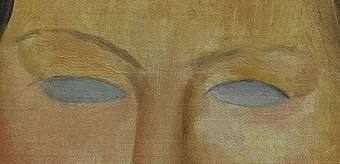

Fig.17a

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, detail of the eyes

Photo: Annette King

Fig.17b

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, photomicrograph of the proper left eye

Photo: Annette King

Fig.17c

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, photomicrograph of the proper right eye

Photo: Annette King

The eyes appear to be simply painted, with black irises and an impasto white highlight (figs.17a–c). White ground has been left exposed at the outer edges of each almond-shaped eye. The eyes are outlined in black, which also delineates the fold of the eyelids. The artist added pale grey to the white of the eyes, painted up to and around the black pupils. There is a little wet-in-wet blending visible in the proper right eye, where the black iris was reinforced over the pale grey area. The centre of the eye was thinly painted, allowing the light peaks of the ground to show through the transparent black, producing a luminous effect. The flesh around the eyes was painted over a warm yellow underpaint, with strokes of more intense pinkish orange, dark red and opaque grey. The upper flesh layer appears to contain more opaque white paint and to have been brushed on with short strokes, drying quickly as it formed the eyelids and the bridge of the nose. The eyes were enlivened by impasto highlights. They are unusually naturalistic compared to other eyes painted by Modigliani and are more reminiscent of his earlier portraits than the later South of France paintings.

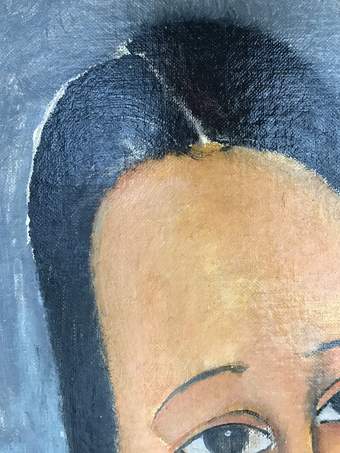

Fig.18a

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, photomicrograph showing swirls of paint where the grey of the background picked up the wet black paint of the hair

Photo: Annette King and Joyce Townsend

Fig.18b

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, detail of the hair showing the parting and scratched white hairs

Photo: Annette King and Joyce Townsend

In contrast to the matte flesh, the hair has the glossy appearance of oil. The paint clearly remained wet for long enough to be picked up by the brush as the grey background was painted, creating small, circular brushstrokes at the outer edge of the hair on the right (fig.18a). A white line of ground was left unpainted for the parting in the hair and a few white hairs at the temple were lightly incised into the paint as it dried, creating texture and detail (fig.18b). This mingling is distinct from the red paint applied for the lips or the paint around the eyes, which could only be blended with difficulty and by applying tiny adjacent strokes before it dried.

The grey background has the same matte appearance as the flesh paint but was applied with longer and more random brushstrokes that are clearly visible in the IRR image (see fig.5). The paint of the white blouse is also matte and appears to be fast-drying, built up with small brushstrokes that follow the drape of the fabric, with the broken grey lines delineating the sleeves applied last of all. The paint used for the curtain is more intermediate in gloss, as though the two types of paint were mixed. More colours were used here – yellow applied after blue – but without creating a discernible pattern or a credible reflection from the sitter’s white costume.

The pigments identified in Madame Zborowska include bone black, vermilion, mid-chrome yellow, chrome orange of a deep reddish orange shade, barium yellow associated with zinc white, synthetic ultramarine, Prussian blue, and dark brown or black natural ochre. All are fine-grained, which suggests artists’ tube paint. These are lightened with lead white, the presence of which is detectable in every colour.27 Paint medium analysis of a relatively glossy-looking paint sample from the curtain indicated non-heat-bodied safflower or walnut oil and lead soaps, which are a degradation product of oil-based paint and lead white pigment.28 A sample of matte paint from the off-white costume consisted of linseed oil and some casein (or, less likely, glue), making it a tempera paint as it was defined at this date.29 Again, metal soaps were present. Madame Zborowska was likely executed using mixtures of artists’ oil tube paint and casein-based tempera paint, with more oil used for the curtain, probably from tube paint, and more tempera for the figure.

Fig.19

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, photographed in ultraviolet light

Photo: Tate Photography

The portrait is lightly varnished with a single thin layer of natural resin-type varnish that pooled in the hollows of the textured paint and is strongly fluorescent in ultraviolet (UV) light due to light exposure (fig.19). Several cross-sections show that varnish was absorbed into the top layer of paint, as does the uneven fluorescence seen in UV light. The considerable yellowing of this thin varnish makes the skin tones appear warmer than originally painted, while its moderate gloss de-emphasises the matte surface of the paint in most areas except the hair. The flesh paint appears particularly patchy; it is possible that the face was retouched, perhaps during the same restoration as the lining process. There are light patches of colour along the nose and to the left of the nose that are rather out of place. The white area under the lips also stands out in UV. The state of the flesh paint today, which differs from the light, fresh appearance of Modigliani’s faces in other paintings, may be explained by later touches of paint.

Comparing Madame Zborowska and The Little Peasant

Fig.20

Amedeo Modigliani

The Little Peasant c.1918

Oil on canvas

1000 x 645 mm

Tate

C257

Fig.21

Amedeo Modigliani

The Little Peasant, short-wave infrared detail showing minimal underdrawing defining the outline of the face and features

Photo: Aviva Burnstock and Silvia Amato, Courtauld Institute of Art

Modigliani’s The Little Peasant (C257; fig.20) was painted in the South of France in 1918, similar to the date and location assigned to the portrait of Madame Zborowska. The two paintings are in the Tate collection and thus could be examined together. The Little Peasant is unlined, possibly on its original strainer and is not varnished. In this condition, it is a good example of how Modigliani’s paintings from the South of France might have looked without significant conservation interventions, retaining a luminosity and matte colour which is compromised in Madame Zborowska by a conservation varnish and possibly additional paint on the face. The Little Peasant is larger than the Zborowska portrait.30 It was painted on a coarser, but more tightly woven, linen canvas, also plain-woven, with a thread density of 23.1 by 21.4 threads per centimetre and a single layer of lead white-based priming, which cross-sections suggest may be oil-based.31 Its underdrawing appears far more assured than that of Madame Zborowska, with each form outlined without hesitation or wavering (fig.21). Like Madame Zborowska it was painted section by section, the paint kept within the drawing lines to leave narrow white borders of primed canvas visible between different forms. Here the drawing tool was clearly fine graphite pencil, identifiable by its appearance under magnification.

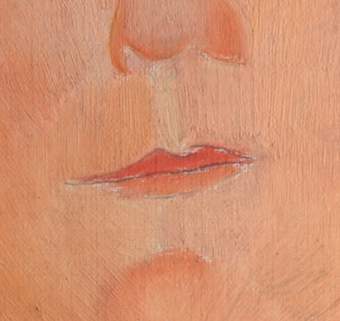

Fig.22a

Amedeo Modigliani

The Little Peasant, detail of the nose, lips and chin

Photo: Annette King and Joyce Townsend

Fig.22b

Amedeo Modigliani

The Little Peasant, photomicrograph of the lips

Photo: Annette King and Joyce Townsend

Common to both paintings are the processes of blocking-in fairly uniform colours for forms, strengthening some of the drawn outlines with fine black lines of paint, then using small brushstrokes of more varied colours to develop modelling. However, the use of grey for shadows and heavy outlines in the lip area of Madame Zborowska is quite different from the treatment of the flesh tones in The Little Peasant. In The Little Peasant, the modelling was achieved mostly with varying flesh tones, as well as with the directional brushstrokes that form the straight or curved shapes in the lower face. The lips are simply rendered with a single layer of dark red for the top lip, painted within the reserve, and paler red for the lower lip, with an outline painted over the colour (figs.22a–b). The treatment of Zborowska’s face is perhaps more reminiscent of Modigliani’s nudes of 1917, where blue or blue-grey ground is used to model the faces.

Almost all the paint used for The Little Peasant is matte, fast-drying and retains brush marks, resembling that used for Zborowska’s flesh. The pigment range is somewhat similar for the two works, except in the flesh tones, where zinc yellow (zinc chromate) was found in Madame Zborowska and not in The Little Peasant. Otherwise, both contain pure lead white for the shirt; vermilion for the lips; a non-fluorescent red lake; a natural ochre for the chair; bone black and lead white for the flesh; synthetic ultramarine; Prussian blue; and a mid-brown earth colour. Black paint in The Little Peasant, less matte than the other colours, was found by medium analysis to contain non-heat-bodied walnut or safflower oil.32 The flesh paint for the right hand was reported to be most likely a linseed oil/casein emulsion, namely a casein-based tempera paint.

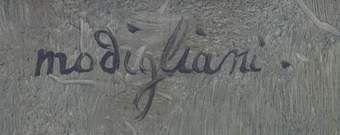

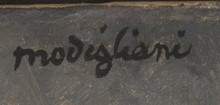

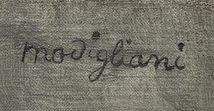

Fig.23

Amedeo Modigliani

The Little Peasant, detail of the signature

Photo: Tate Photography

Fig.24

Amedeo Modigliani

Madame Zborowska, detail of the signature

Photo: Tate Photography

The signature ‘modigliani’ on The Little Peasant was painted wet-in-wet (fig.23), and the French title ‘le petit paysan’ was applied over drier paint. Both inscriptions have a more ‘personal’, rapidly executed appearance than the rather bland-looking signature on Madame Zborowska (fig.24). This latter signature, at the top right of the painting, lies under the varnish but is very even in appearance; it does not run out of paint halfway, which is often seen in Modigliani’s signatures.33

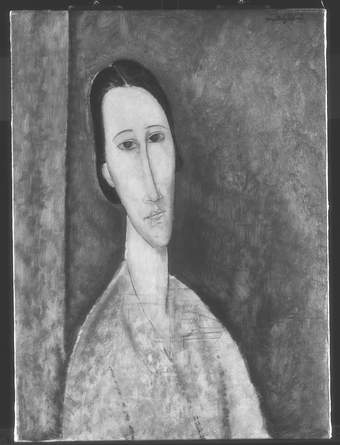

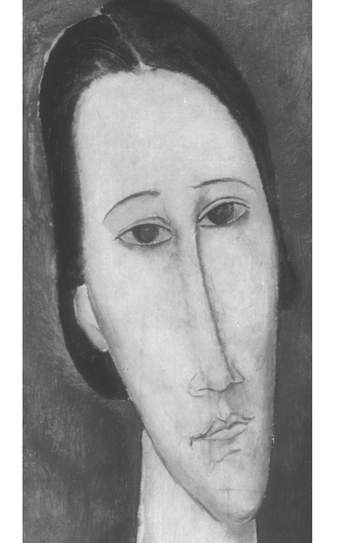

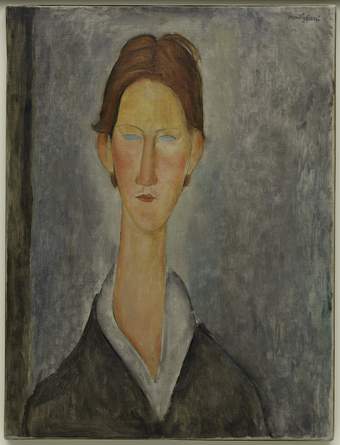

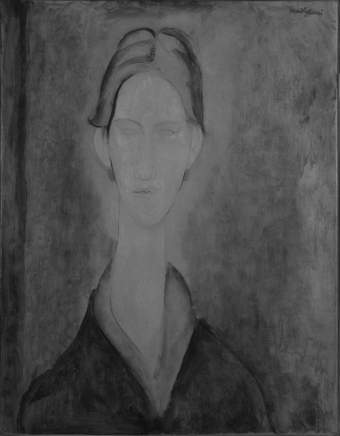

Portrait of a Student

Fig.25

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Student (L’Etudiant) c.1918–19

Oil on canvas

609 x 460 mm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Photo: Kristopher McKay

The second painting analysed in this study is the Guggenheim’s Portrait of a Student (fig.25), a depiction of an unidentified sitter that was not included in any of Ceroni’s volumes of Modigliani works. Set within a shallow space, the figure is serious, with a diminutive, pursed mouth and intense blue eyes that appear at once vacant and searing. The work has been referred to variously as ‘The Student’ and ‘Portrait of a Woman’.34 This last title intimates some ambiguity as to the gender of the sitter. The faint outline of a moustache, however, betrays the model to be a young man. It was relatively rare for Modigliani to depict a man with an open neckline, but some examples do exist, such as the portraits of Gaston Modot (1918; Centre Pompidou, Paris; C279), Léopold Zborowski 1918 (Netter Collection, Paris; C227) and Young Man with Red Hair, Seated (Garçon aux cheveux roux (assis de face)) 1919 (private collection; C301), which is often thought to depict the same model as the Guggenheim painting.35 The facial features of Young Man with Red Hair, Seated are strikingly similar to those of Portrait of a Student, and both paintings have an indication below the nose of a moustache, suggesting that the sitter is a young man.

Curiously, there is a near identical painting to Portrait of a Student, also absent from the Ceroni publication, in a private collection.36 This other version of the painting travelled to the Guggenheim in 1971 for examination, imaging and comparative viewing. Although Modigliani often depicted a model multiple times, there is no evidence of any other works that are so close in composition. Further research is necessary to establish the relationship between these two works.

The provenance of the Guggenheim painting dates back to 1933, when it was known to be in the collection of the Paris-based dermatologist Raymond Sabouraud. By 1937 there is a very slight possibility that it may have been with Mrs Healey in London.37 It had certainly passed to the dealer Jacques Dubourg in Paris by 1938.38 That same year Dubourg sold the painting through the James Wilson and Company Gallery in Ottawa to the Ottawa-based Harry Stevenson Southam, who was one of the foremost Canadian collectors of nineteenth-century French art and then chairman of the Board of Trustees at the National Gallery of Canada. Southam began selling his French collection in the 1940s in order to accommodate his growing Canadian collection. In 1945, Portrait of a Student went through the Dominion Gallery, Montreal (Rose Millman and Max Stern, proprietors) and Fine Arts Associates, New York (Otto Gerson and Siegfried Thalheimer, proprietors), at which time it was purchased by the Nierendorf Gallery, New York. The Guggenheim acquired the painting from Nierendorf in the same year.39

Stylistically and technically, Portrait of a Student has a relationship with the works Modigliani made during his time in the South of France40 – where he sought refuge in 1918–19 from the devastating impact that the First World War was having on Paris – and with those he made after his return to the French capital. The subject of the painting could be one of the locals, or ‘rural archetypes’, whom he sometimes painted there.41 Modigliani often depicted these young sitters with rosy cheeks, perhaps reflecting the idealised healthy glow of rural life, and they tend to gaze straight out at the viewer with a certain solemnity. The clothes and demeanour of the young man in the Guggenheim picture, however, suggest a more patrician background. The sitter is well groomed, with carefully coiffed hair and a noticeably upright posture, suggesting an urban model and that the work was painted after Modigliani’s return to Paris in late May 1919, shortly before his death. The cool blue and green tones of the background are juxtaposed with the orange, pink and ochre flesh tones, evoking the colours of the post-impressionist painter Paul Cézanne, whom Modigliani was known to admire. The overall tonality is less luminous than that of those works painted in the sun-drenched environment of the South of France.42

The Guggenheim painting is executed in oil on a fine, plain-weave linen canvas that measures 61.3 by 46.4 cm, which corresponds to a standard paysage 12 canvas rotated on its side. A high-resolution X-radiograph analysed with thread counting software indicates a horizontal (weft) thread density of 21.4 threads per centimetre and a vertical (warp) thread density of 26 threads per centimetre, with a more pronounced thread count deviation in the weft direction.43 This thread count corresponds to Modigliani’s Girl in a Sailor’s Blouse 1918 (C249) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, which is a similar size canvas.44 A wax-resin lining applied in 1957 flattened the structure of Portrait of a Student, causing the canvas weave to become more prominent. The painting is mounted on a non-original stretcher, most likely changed during the lining process.

In raking light, Portrait of a Student exhibits significant horizontal cracking, likely caused by rolling the canvas, perhaps to be shipped from the South of France to Paris, or later for transport to North America. This cracking pattern and a small tear were presumably the reasons for the lining, but no record of the treatment exists; the cracks have a tendency to lift and have been subsequently treated to set them back into place. The small tear in the central area of the sitter’s jacket was mended, filled and in-painted. There is an application of ‘Ozenfant’ wax on the surface, beneath a final poly-butyl methacrylate varnish. The removal of the varnish in the 1980s restored some of the brushwork and matte quality of the paint, but it still exhibits some burnishing, gloss and saturation caused by the 1950s conservation treatment. Given the dilute application of paint, it is likely the surface once appeared much drier, with varied surface textures created by passages of thick and thinner paint. Unfortunately, the wax penetrated the surface and homogenised the overall appearance.

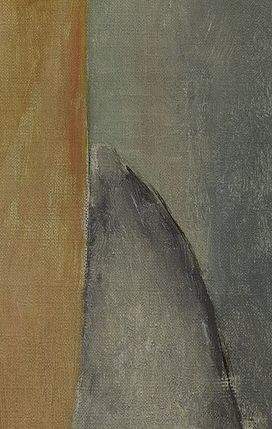

Fig.26

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Student, detail of the neck

Photo: Kristopher McKay

The portrait is painted on a pre-primed commercial lead-white ground, with thin, open brushwork in the background, hair and clothes, using different size brushes and a range of types of mark-making. Texture is created in the background with rapid, splayed brushstrokes and short curved strokes made with a bristle brush that reveal the ground below. Small directional brushstrokes define the features of the face and neck, and thin, dilute outlines accentuate the forms. Both the light ground and the stylistic devices relate to Modigliani’s later work made in the South of France, when he tended to leave exposed areas of white ground along the edges of forms.45 The ground layer is visible along the borders of the upper hairline and cowlick, proper left cheek, collar and neck (fig.26).

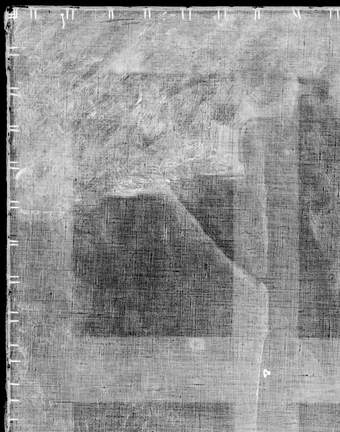

Fig.27

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Student, X-radiograph

Photo: Guggenheim Conservation Department

An X-radiograph of Portrait of a Student (fig.27) provides limited information, given the strong absorption of X-radiation by the lead white ground that overwhelms the thin application of paint. Diagonal strokes visible in the X-radiograph may indicate ground application with a trowel, similar to the sweeping lines in the X-radiograph of Madame Zborowska. A thicker build-up of paint around the lips, chin, ears, hair and collar is indicated by dense white lines. It differs from X-radiographs of Modigliani’s other paintings in that the brushwork in the forehead and around the mouth is uncharacteristically expressionistic. These passages are less meticulously painted than other areas of the face, which are formed by fine directional strokes made with a tiny brush; these small, regular strokes characterise the faces of many of the artist’s later portraits. A faint scumbled halo of thicker paint is visible around the head and neck, where the grey-blue of the background was mixed with white. This was painted after the face was completed and follows the contours of the head and neck in a wet-in-wet technique that picked up brown from the hair and flesh tones, resulting in pink hues around the figure.

Fig.28

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Student, infrared reflectogram

Photo: Guggenheim Conservation Department

There is some visible graphite or hard charcoal drawing when the painting’s surface is viewed under magnification, although it is not as fluid and confident as other works from this period. An IRR image reveals this fine drawing, delineating the contours of the face, lips, eyes and neck (fig.28). This line is visible in certain areas, where the rapid paint application left passages of exposed ground along the outlines of the forms. Beneath the chin there appears to be some smudging of the graphite to render a shadow, indicating that the chin may have been altered to make the face shorter. A quickly executed thin line defines the proper left of the v-shaped neckline. The contours of the almond-shaped eyes are sketched in fine lines and there is a small curl at the outside corner of the proper right eye. A darker line separates the lips, with faint drawing defining the upper lip contour and nose. There is a dilute blue outline below the paint, which is mostly covered by subsequent paint application; blueish black and thicker black outlines selectively reinforce the forms. These lines go both over and under the flesh tones, suggesting that the artist made changes to the flesh after outlines were drawn.46

Fig.29

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Student, detail of the eyes

Photo: Kristopher McKay

The eyes are simply rendered in a solid blue tone, which appears to be painted over a reserve (fig.29). A faint line drawn with a dilute blue paint, applied both under and over the blue eyes, delineates the upper and lower lid, while a darker blue/black line reinforces the upper one. Flesh tones were then painted with short, fine brushstrokes up to the lids, partially obscuring the blue outlines. The upper eyelids are shaped with a curved stroke of rosy orange, bracketed by pale pink brushstrokes. On the proper right this stroke appears to be rubbed smooth. Beneath the proper left eye, a curved shape forms a highlight with exposed ground and translucent paint. The shadows on the bridge of the nose and under the chin are brown and ochre, with a small amount of grey around the eye.

Fig.30

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Student, detail of the lips

Photo: Kristopher McKay

Vermilion mixed with white depicts the cheeks, nose and outer ears, with ochre, brown and grey shadows. The flesh is mostly built up with short directional brushstrokes that are controlled and follow the forms. There is a bright highlight under the proper left eye and above the upper lip. A few short, thick strokes of vermilion mixed with white form the lips (fig.30), picking up and partially obliterating the heavy line, visible in the IRR image, that separates the upper and lower lips. The lower lip is plumper than the upper lip, with a pink highlight, and the flesh tones are painted wet-in-wet around the lips, picking up some red pigment. There are variegated tones of red in the lips, from darker brownish red to touches of pure vermilion and paler reds mixed with white. There is no final outline to reinforce the lips.

Fig.31

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Student, detail of the central parting of the hair with scraping marks

Photo: Kristopher McKay

A thick black stroke in the hair delineates the proper right contour of the forehead. The hair features both thin and thick paint application, with white ground visible where the brush scrubbed the surface. The parting is rendered with a dry brush and short, diagonal brushstrokes, scraped into the wet paint (fig.31). A stroke of light grey occupies the space between the hair and the swiftly painted cowlick, which was painted wet-in-wet.

The pale grey halo around the head and shoulders partially covers the edges of the figure, indicating that the portrait was complete before the final touches were applied to the background. A dark, vertical, architectural stripe along the proper right edge is a convention Modigliani often used in portraits to define the space. There are cool blues, violet greys and emerald green tones in the background. Reds and yellows from the figure were picked up by the greys in the background during the wet-in-wet process.

Overall, the brushstrokes are quite pronounced, likely indicating bristle brushes and stiff pastose paint that did not level. There is a wide, swathe-like horizontal brushstroke at the bottom of the composition, which appears to have been made by scraping through partially wet paint with a dry bristle brush. The collar is painted thinly, with some thick, rapid swirls, and the jacket is quickly rendered with scattered multidirectional brushwork. The background is executed with rapid dabbing, swirling and scumbling, while the face and neck are carefully defined with short, directional brushwork.

The pigments identified through portable X-ray fluorescence include ubiquitous lead white and calcium carbonate (chalk). Lead white is mixed with vermilion in the lips and rosy cheeks; with blue in the eyes (possibly ultramarine); with chrome yellow or chrome orange in the flesh tones; and with various blues and greens in the background, which contains chrome, plus small amounts of iron and zinc. The dark brown/black outlines contain significant amounts of iron and calcium, denoting bone black or iron-based pigments. No media analysis was undertaken, but penetration of wax following the 1957 treatment would make media identification difficult.

Fig.32

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Student, detail of the signature

Photo: Kristopher McKay

In the upper right corner, rounded, cursive, lower-case letters form the signature, which was created with a thin brush and dilute black paint, applied when the underlying layer was dry (fig.32). Small circles mark the tittles above the letter ‘i’. There is horizontal cracking through the signature, as in the rest of the work. The entire signature has an even density rather than trailing off when the brush is less loaded with paint. In contrast to the inscriptions for both Madame Zborowska and The Little Peasant, the ‘o’ and the ‘d’ are connected, and the signature leans diagonally to the right.

Conclusions

It is tempting to infer from the study of the Tate and Guggenheim paintings that there is substantial evidence of a similarity in materials and technique to justify including both paintings in Modigliani’s oeuvre. The analysis carried out to date shows that no materials were used that would not have been commonly available during the artist’s lifetime, and elements of the technique align with works painted after Modigliani’s move to the South of France in 1918. Lead white was a popular white pigment throughout the twentieth century. Safflower oil was coming into more frequent use as the oil type used in artists’ tube paint, and walnut oil had long been used. The casein-based tempera in Madame Zborowska might appear distinctive today, but there were several such products readily available in Paris and elsewhere, some of them produced in Italy and advocated by Italian artists such as Gino Severini.

The provenance known at present does not trace these paintings to Modigliani’s lifetime, but to the mid-1920s, when Zborowski held the bulk of Modigliani’s works, and Portrait of a Student can be placed in Sabouraud’s collection. Modigliani’s paintings increased in value after his death in January 1920. It is possible that Zborowski commissioned artists to ‘finish’ works and possibly even to create ‘Modiglianis’. A newspaper clipping from 1922, for instance, records that ‘a well-known paintings dealer has just made a proposition to the painter Coubine, allocating him two thousand francs per month for the manufacture of four Modiglianis’.47

There are several aspects of Madame Zborowska that have close links with other works analysed as part of the current study, suggesting that the portrait may have begun life with Modigliani. The canvas is part of a cluster of paintings from the same roll of canvas and these ‘bolt mates’ are included in the 1970 Ceroni publication. It also has a very similar double ground to Standing Nude (Elvira), suggesting a common supplier. The mysterious line drawings under Madame Zborowska are reminiscent of Modigliani’s few landscapes. Modigliani stated in a letter to Zborowski that he disliked painting landscapes, and therefore could well have abandoned such a project halfway through, turning the canvas around and starting again.48 The dense, lead-containing pale blue paint, now in the lower right corner, could have been the brushy beginning of a sky, following the contours of a landscape design, originally in the top left corner of the canvas. The brushy background and aspects of the clothes and curtain are similar to other compositions analysed in this study. In terms of materials and brushstrokes, however, the face diverges from other portraits by Modigliani. The flesh does not have the subtlety and sophistication of other paintings in the study. The paint is flat, dense and thickly applied in places, without the subtle variations of shading in the cheeks of The Little Peasant, for example. Each feature has a fairly heavy black linear outline, whereas in most paintings the outlines are more subtle. In The Little Peasant, for example, the black contours defining the face, eyes, nose and lips are discreet, and the flesh is fresh and luminous, using only directional brushstrokes to delineate form and nuances of colour to create the rosy cheeks. In Madame Zborowska, individual features are defined by underlying colour or grey shading. There are planes of colour that do not blend or make sense as a whole. This patchiness is particularly evident when the painting is viewed in UV light. There appears to be flesh colour underneath the upper layer and in places the paint seems to have been scraped back, and thick applications of paint laid on top. A later repainting of the face would seem the most likely explanation for these anomalies.

Details of the brushwork in Portrait of a Student are perhaps more reminiscent of Modigliani’s known technique, but it could be argued that it lacks some of the luminosity of his South of France paintings. The technique used to build up the facial features, as seen in the X-radiograph, is somewhat atypical of Modigliani, particularly in the chin area, where the brushstrokes are not the short parallel lines that one would expect, and the forehead is strangely mottled. In addition, if this is a late portrait, it lacks the virtuosity of drawing that has been identified in many of Modigliani’s paintings from that period.49 The palette is similar to other works, but these pigments were in common use at the time. The dilute blue line beneath the paint is a convention that Modigliani was known to use, and the tight working of the face in juxtaposition with the rapid, loose brushwork in the background is characteristic. In addition, the canvas thread count closely relates to another work in Ceroni, Girl in a Sailor’s Blouse.

It is possible that Portrait of a Student is the same sitter as that in Young Man with Red Hair, Seated, which was included in the 1970 Ceroni catalogue, and it could theoretically have been a study for the completed larger work. There also remains the question of the other portrait of the same format, held in a private collection, with some differences in the overall palette and paint application.

Both Madame Zborowska and Portrait of a Student remain in the no man’s land that Modigliani’s paintings inhabit when they are not included in the Ceroni publication. It is not possible to differentiate them from other works by their materials, and it remains a matter of opinion as to whether the paintings compare favourably to other paintings in the artist’s oeuvre. There are many factors that link these paintings to other works by Modigliani, but for the time being it must be left to the viewer to make their own comparisons.