Not on display

- Artist

- Marcel Mariën 1920–1993

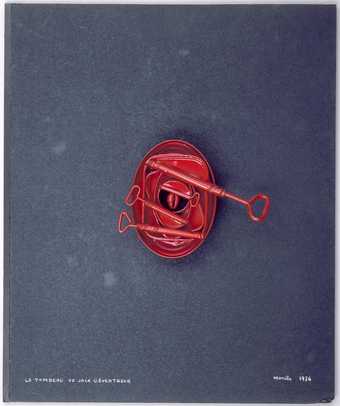

- Original title

- La Danseuse étoile

- Medium

- Starfish and plastic shoe on card

- Dimensions

- Object: 360 × 260 × 47 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the artist's estate 2005

- Reference

- T12051

Summary

Star Dancer 1991 is a mixed-media assemblage featuring a real, light brown starfish with a small plastic heeled shoe attached to the lower-right limb of its splayed body. The shoe, which is covered in silver coating, is seen in profile. These two elements are mounted on a piece of dark blue baize-covered card that is set in a dark brown stained wood box frame fronted with glass. The date, artist’s name and the title of the work in French (La Danseuse étoile) are written in black across the bottom of the card.

The work was made by the Belgian artist, writer and publisher Marcel Mariën in Brussels in 1991, just two years before his death. Exhibition histories and labels attached to the back of the work suggest that it remained in the artist’s collection until he died and that it was first displayed as part of Le Lendemain de la mort (The Day After Death), a 1994 retrospective exhibition held at the Musée Ianchelevici in La Louvière, Belgium (Marcel Mariën 1994, pp.97–101).

The work’s original French title, La Danseuse étoile, is a term that is traditionally used to refer to the highest ranking position that a female dancer can reach at the Paris Opera Ballet – equivalent to ‘prima ballerina’ in Italian. In combining the idea of a ‘star dancer’ with an actual starfish ‘wearing’ a dancing shoe, Mariën creates a visual pun with a comic effect. The monograph published to accompany his 1994 retrospective argues that the process of giving works such as Star Dancer a title helps reinforce their meaning, with the act of titling being part of the work’s making and essential to its intellectual completion (Marcel Mariën 1994, p.13).

Throughout his career Mariën made use of a variety of textual and visual forms in his artistic practice. These often involved an element of playfulness in which he offered alternative depictions or interpretations of familiar concepts or objects. The literary magazine that he edited from 1954 to 1960, Les Lèvres Nues (The Naked Lips), employed a sarcastic tone, provocative statements and examples of wordplay (see J.H. Matthews, The Custom-House of Desire: A Half-Century of Surrealist Stories, Berkeley and Los Angeles 1975, p.203). The subversive strategies and whimsical tone of this publication are echoed in works such as Star Dancer.

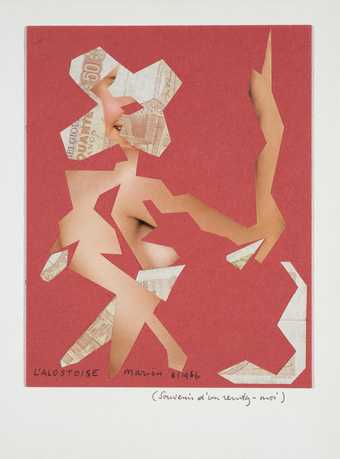

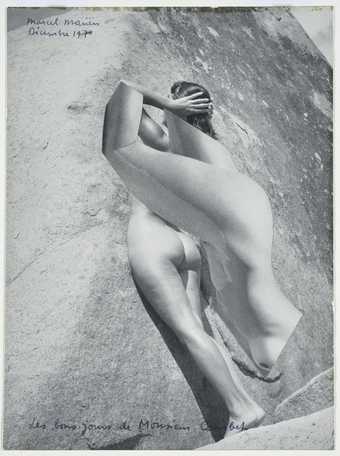

Mariën became more consistently involved with visual art from 1967, and regularly exhibited collages, paintings, drawings and sculptures, such as Why We Are Fighting 1970 (Tate T12045). These works employed a surrealist ‘poetics of producing disturbing encounters’, as cultural theorist McKenzie Wark has described it, by juxtaposing unexpected elements and objects to reveal hidden meanings (McKenzie Wark, ‘Marcel Mariën’, Public Seminar, 27 January 2016, http://www.publicseminar.org/2016/01/marcel-marien/, accessed 9 August 2018). Art critic Silvano Levy understands this as an ‘artistic form of mischief’ that can be seen in light of Mariën’s connection with the Belgian surrealists early in his career (Silvano Levy, ‘Obituary: Marcel Mariën’, Independent, 2 October 1993, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-marcel-marien-1508248.html, accessed 9 August 2018). After encountering Belgian surrealist René Magritte’s work in 1937, Mariën sought out the artist and became apprenticed to him and others in his circle, such as the poet Paul Nougé. Mariën produced various paper collages, a practice employed frequently by French and Belgian surrealists, who collected and reused images in unusual juxtapositions to assert the value of the unconscious and the universe of dreams (see, for example, Mariën’s Sculpture Friends 1974, Tate T12047, and The Woman from Alost 1966, Tate T12042). Furthermore, Magritte’s use of conceptual jokes and enigmatic combinations of image and text, seen in works like The Treachery of Images 1929 (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles), are found in many of Mariën’s assemblages, such as Les Songes de la Clef 1970 (private collection).

As the 1994 monograph suggests, Mariën’s practice of framing or boxing found objects has the effect of sanctifying them, as well as modifying the individual objects’ meanings. In addition to Star Dancer, the artist produced several boxed assemblages combining found objects ways, such as The Tomb of Jack the Ripper 1976 (Tate T12048). The use of playful combinations displayed in boxes calls to mind works by American surrealist Joseph Cornell, who similarly dedicated himself to this practice, as is seen, for instance, in his juxtaposition of miniature plastic lobsters alongside the cut-out of a dancer in the box work Untitled (Zizi Jeanmaire Lobster Ballet) c.1949.

Further reading

Marcel Mariën, Brussels 1994, p.13, reproduced p.13.

Luisa Karman

August 2018

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Mariën published the first monograph about Rene Magritte in 1943 and became the principal historian of the Belgian surrealist group, as well as an associate of the Situationists. In his own photographs, collages and assemblages, Mariën continued the surrealist tradition of making unexpected combinations of objects to reveal hidden or poetic meanings. In Star Dancer, the addition of a toy shoe creates a visual rhyme between a starfish and the leg of a dancer.

Gallery label, August 2012

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- leisure and pastimes(3,435)

-

- music and entertainment(2,331)

-

- dance(296)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- shoe(179)

You might like

-

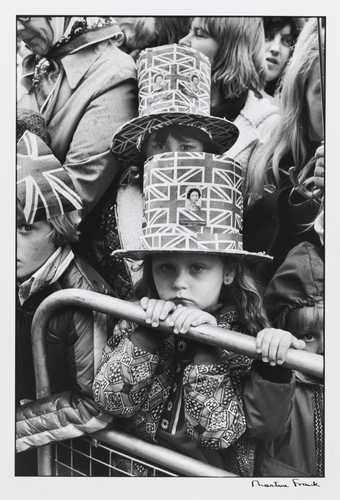

Martine Franck Greenwich, London

1977 -

Martine Franck Chelsea Royal Hospital, London

c.1973, later print -

Francis Alÿs The Last Clown

1995–2000 -

Marcel Mariën The Woman from Alost

1966 -

Marcel Mariën The Prostitute r...

1966 -

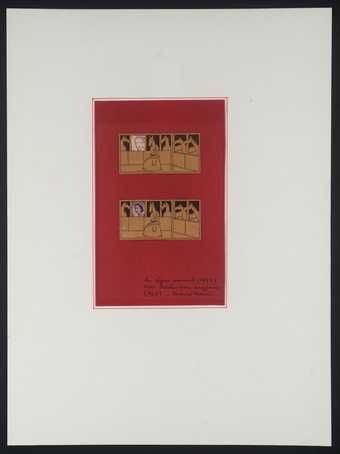

Marcel Mariën The Animal Kingdom (1953) with English Translation (1967)

1967 -

Marcel Mariën Why We Are Fighting

1970 -

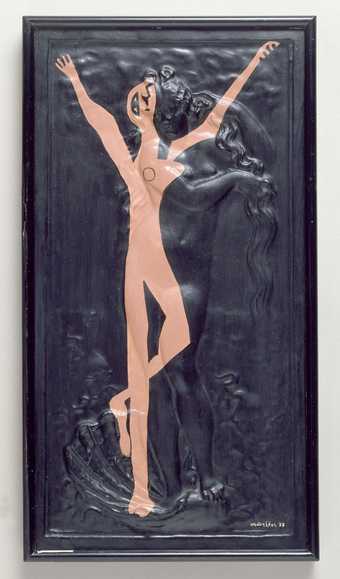

Marcel Mariën Monsieur Courbet’s Good Days

1970 -

Marcel Mariën Sculpture Friends

1974 -

Marcel Mariën The Tomb of Jack the Ripper

1976 -

Marcel Mariën All Gum

1979 -

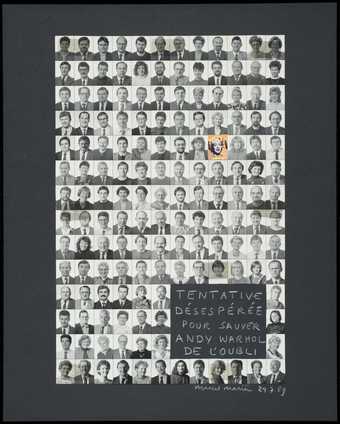

Marcel Mariën Desperate Attempt to Save Andy Warhol from Oblivion

1989 -

Francis Alÿs Guards

2004 -

Carsten Höller Sliding Doors

2003 -

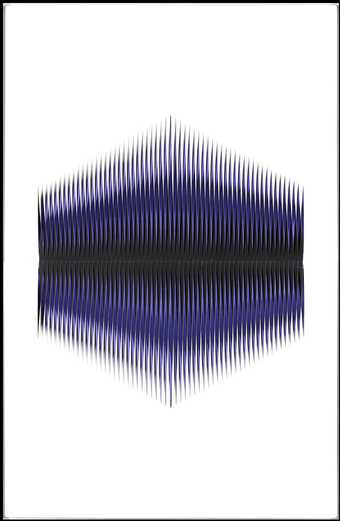

Walter Leblanc Torsions, CO 459

1974