Not on display

- Artist

- Daria Martin born 1973

- Medium

- Film, 16 mm, projection, colour and sound

- Dimensions

- 7min, 30sec

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 2007

- Reference

- T12743

Summary

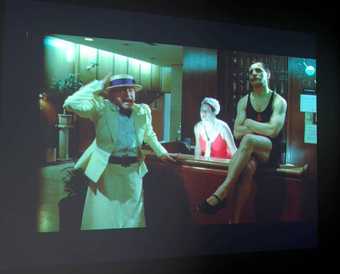

Birds 2001 is the second in a trilogy of films. It is preceded by In the Palace 2000 (Tate T12744) and succeeded by Close-up Gallery 2003 (Tate T12175). The film follows five dancers on an all-white, moving set. At first they wear highly stylised, predominantly white costumes before switching to all-white leotards and coloured cellophane headdresses with matching extensions on each of their fingers. The dancers form complex compositions comparable to abstract paintings and hold their poses in tableaux. At other points they explore parts of the moving scenography. Birds ends just after the performance stops and the dancers relax, and one of them reacts to the camera’s presence.

The costumes, props and sets used in Birds are made out of everyday materials and appear makeshift. Parallelling the coloured cellophane of the headdresses, the set comprises clear and coloured Perspex shapes intersected by javelin-like rods. There are also coloured balls and a large wheel, inside which a dancer stands and rolls across the set. The costumes and props, as well as the choreography and compositional sequences, pay homage to the German Bauhaus artist and choreographer Oskar Schlemmer’s (1888–1943) Triadic Ballet (Das Triadische Ballett) of 1922. As Schlemmer’s ballet transformed the dancer’s bodies into geometric shapes, in Birds abstract forms and the human figure collide. However, just as the work translates the dancer’s interactions into compositions resembling the plastic artworks, it also shows the interactions between the dancers. This is particularly evident in the moments of repose at the end of the film. In this way Birds exposes the private world of the group as well as the fantasy, artificial world of theatre.

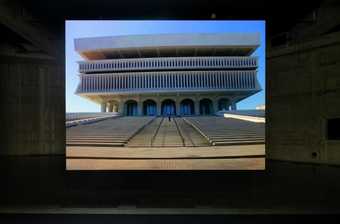

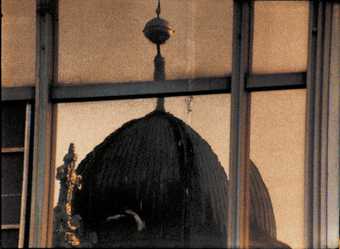

Like Birds, In the Palace also cites Schlemmer’s choreography, but this time his 1927 Slat Dance. In addition to this, the dancers in this work perform tense exaggerated poses derived from the publicity stills of other figures of modernist dance including Martha Graham, the Ballets Russes and Josephine Baker. In contrast to the all-white scenography in Birds, the dancers in this film occupy a black set, which features a scaled-up version of Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture The Palace at 4am 1932 (Museum of Modern Art, New York). Martin has commented on her use of this sculpture as ‘a desire to literally realise my own fantasy to inhabit this small sculpture, to blow it up to human dimensions and to populate it with performers’ (quoted in Kunsthalle Zürich 2005, p.76).

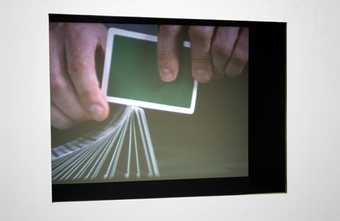

The third film in the trilogy, Close-up Gallery, breaks with the setting of the stage and the small community of dancers, taking place in what seems to be a backstage space. The action takes place between two people, a sleight-of-hand magician and a woman to whom he is teaching his tricks. The artist has commented:

a flow of learning appears to pass from the man to the woman, but his fingers too falter, and the control is sometimes all hers. Following the two performers’ tentative exchange of glances, spray painted cards dance free from their manipulations, as if dramatizing inner worlds in motion.

(Martin, statement on the artist’s website, no date, http://dariamartin.com/closeup-gallery/, accessed March 2007.)

In this way, each of the films explores the relationships struck up within performances and between performers, as well as the contingency of the space in which these actions take place.

Although trained as a painter it is as a filmmaker that Martin has achieved recognition. She draws her inspiration from early twentieth century painting, sculpture, fashion and stage and dance production. Alongside direct quotation of these sources that, taken together, describe a vision of the early modernist ideal of ‘total artwork’, Martin’s films also confront issues of artificiality and illusion through the sets, costumes and props; through the editing and framing of film narrative; and through the particular performances of the actors that all at different levels both reveal and revel in artifice – what Martin refers to as ‘low tech-magic’ (quoted in Bowman 2005, p.66). As Martin has explained:

Film, like art, is artificial, its codes of language invented. In my films the fakery of their making is foregrounded; shadows appear on backdrops; the actors drop their poses; camerawork is sometimes shaky; narrative is subjugated to a more musical structure. I want to seduce viewers into an imagined space but to allow them ways out of it, seams through which to breathe. Perhaps as a springboard for a sense of agency and expressive power, which for many years had gone out of style in the art world, my films reference modern art and performance, particularly that of Oskar Schlemmer’s Bauhaus. I became interested in re-invigorating an image of this period partly as a way of re-imagining a shadow of 20th-century art history: the vulnerable, performative underbelly of the body of Modernism.

(Martin, artist’s statement, in Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art 2005, unpaginated.)

Martin’s examination of early twentieth century modernism echoes the interest of her peers at University of California Los Angeles who, through the example of Charles Ray, were examining in a similar way mid-century modernism such as Anthony Caro’s sculptures and American colour field painting.

Further reading

Daria Martin, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthalle Zürich, Zürich 2005.

Uncertain States of America, exhibition catalogue, Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, Oslo 2005, p.78.

Rob Bowman, ‘Daria Martin’, Beck’s Futures, exhibition catalogue, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London 2005, pp.65–7.

Andrew Wilson

March 2007

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- photographic(4,673)

- universal concepts(6,387)

-

- artifice(96)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- visor(14)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- legs crossed(147)

- sitting(3,347)

- woman(9,110)

- group(4,227)

- dress: fantasy/fancy(506)

-

- theatrical costume(124)

You might like

-

Tacita Dean CBE Disappearance at Sea

1996 -

Matthew Barney Cremaster 5

1997 -

Shirin Neshat Soliloquy

1999 -

Trisha Donnelly Untitled

2003 -

Jesper Just Bliss and Heaven

2004 -

Daria Martin Closeup Gallery

2003 -

Tacita Dean CBE Palast

2004 -

Bethan Huws Singing for the Sea

1993 -

Tacita Dean CBE Kodak

2006 -

Ulla von Brandenburg Around

2005 -

Catherine Sullivan The Chittendens: The Resuscitation of Uplifting

2005 -

Daria Martin In the Palace

2000 -

Runa Islam First Day of Spring

2005 -

Matthew Buckingham Situation Leading to a Story

1999 -

Nashashibi/Skaer Why Are You Angry?

2017