Not on display

- Artist

- Leonard McComb 1930–2018

- Medium

- Bronze and gold leaf

- Dimensions

- Object: 1760 × 522 × 465 mm, 118 kg (Gross 241kg)

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery in honour of Richard Morphet, Keeper Modern Collection 1986-98, 1998

- Reference

- T07466

Summary

Although Leonard McComb is perhaps best known as a painter and draughtsman, he originally trained as a sculptor at the Slade School of Art in the late 1950s and has continued to sculpt throughout his career. His luminescent paintings, particularly the watercolours, are manifestations of an understanding of nature as a force that is indivisibly physical and spiritual. For McComb, nature's 'forms and shapes radiate from a centre. This may be described as a tension; the anthropologists call it Mana. It is the name given to that force immanent in all things, not merely men and animals, but even inanimate objects like rocks and sticks - an elemental force manifested universally' (quoted in Hyman, p.66). Richard Morphet suggests that this immanent force is implied through the radiant reflectiveness of McComb's bronze sculptures, of which Portrait of a Young Man Standing is one. McComb himself has compared the glowing reflection of these works to those of Constantin Brancusi, ' which shimmer the air around them with the light of muses' (quoted in Morphet, p.71). McComb's conscious references to ancient Egyptian art through the golden surface of the sculpture and the pose and baldness of the figure may indicate the pantheistic nature of this force.

The actual model for the work was an art student at the West of England College of Art, Bristol, where McComb was a full-time teacher in drawing, painting and sculpture from 1960-4. McComb began the sculpture in 1962, but after six months he abandoned the first pose and started on this image, which he worked on for a further year. Numerous preparatory and technical drawings were made during this period, but have since been destroyed by McComb. In 1963 the model was cast in plaster (artist's collection) and then in bronze (Arts Council Collection), which was polished. Throughout the various processes McComb continued to modify the work so as to reveal the unique details and asymmetries of the model's body; the bronze version was not finished until 1977. Tate's version, the only gilded bronze cast, was made in 1983. It was gilded by McComb's wife, Barbara, and an assistant.

The original development period of 1962-3 took place against the backdrop of one of the Cold War's most dangerous phases. In quick succession the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962), President Kennedy's assassination (1963) and the escalation of the Vietnam War (1954-75) illustrated the destructive power of mankind. McComb, who was deeply concerned by these events, deliberately conceived Portrait of a Young Man Standing as a positive image of humanity. He has described the fundamental purpose of the sculpture as an attempt 'to create an image of a whole person, his physical and spiritual life being inseparably fused [and implying] the embedded capacity for powerful and gentle action, both physical and intellectual' (quoted in Morphet, pp.68-9). The man's youth, his slightly upward gaze and his pose with one hand clenched and the other relaxed are intended to evoke these qualities. Twenty years later, McComb's continuing concerns about the Cold War were combined with a sense that the individuality and inner life of people was being subjugated in the modern world. The close attention given to detail reveals fully the particular physique of the figure and underscores the individuality of the model.

Portrait of a Young Man Standing was first exhibited at McComb's retrospective exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery, London in 1983 and was shown a year later at the Tate Gallery's exhibition The Hard-Won Image. In 1990 the work caused considerable controversy when it was sited in the aisle of Lincoln Cathedral as part of The Journey exhibition; the Dean of Lincoln, concerned about the work causing public offence, first had the figures's genitals covered with a skirt and then had the sculpture removed to a more discreet site. In protest, McComb withdrew the piece from the exhibition. He was immediately invited to display the work for a second time at the Tate Gallery.

Further reading:

Richard Morphet, Leonard McComb: Drawings, Paintings, Sculpture, exhibition catalogue, Serpentine Gallery, London 1983, pp.68-9, reproduced pp.64-5, cat.no.102a and 102

Timothy Hyman, 'Leonard McComb: Body and Spirit', London Magazine, vol. 22, no.5 and 6, August and September 1982, pp.64-73

Toby Treves

*June 2000

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

At either end of the Duveen Galleries you can see a sculpture made in response to events during the Cold War. Of particular significance was the civil war in Vietnam (1954-75), the most famous and most bloody of several ‘proxy wars’ fought between western powers and Communist regimes. Each artist addressed that situation in very different ways.

Though this gilded version of Leonard McComb’s Portrait of a Young Man Standing

was made in 1983, the original version was completed in 1963. Its development was set against the backdrop of the Cold War: specifically, the rapid succession of the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962), President Kennedy’s assassination (1963) and the escalation of war in Vietnam. Concerned by these demonstrations of humankind’s destructive potential, McComb conceived the sculpture as a positive image of humanity. He has described it as an attempt ‘to create an image of a whole person, his physical and spiritual life being inseparably fused [and implying] the embedded capacity for powerful and gentle action, both physical and intellectual’. Later, McComb’s continuing concerns about the Cold War were combined with a sense that the individuality and inner life of people were being subjugated in the modern world.

Gallery label, February 2010

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- universal concepts(6,387)

-

- energy(101)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- standing(3,106)

- man(10,453)

- male(959)

- mysticism(2,612)

-

- spirituality(739)

You might like

-

Fritz Wotruba Standing Figure

1949–50 -

Leonard McComb Tulips

1975–9 -

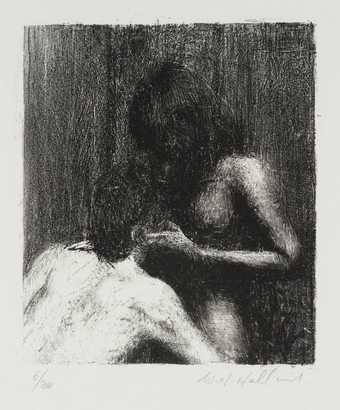

Harry Holland Lovers

1982 -

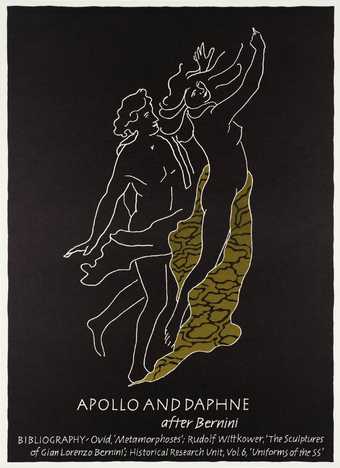

Ian Hamilton Finlay Apollo and Daphne, after Bernini

1977 -

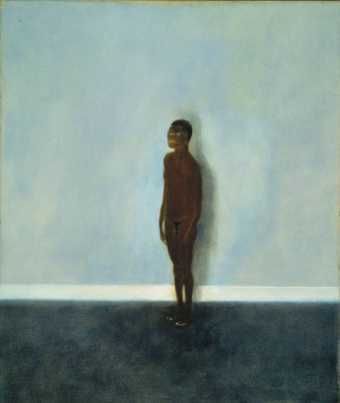

Craigie Aitchison Model Standing against Blue Wall

1962 -

Alberto Giacometti Standing Woman

c.1958–9, cast released by the artist 1964 -

Alberto Giacometti Standing Woman

c.1958–9, cast released by the artist 1964 -

Leonard McComb Portrait of Mrs Lilian Kennett

1976 -

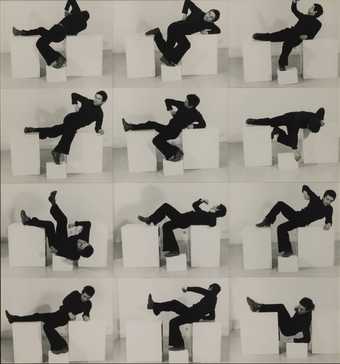

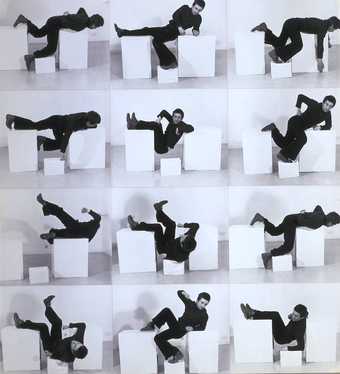

Bruce McLean Pose Work for Plinths I

1971 -

Bruce McLean Pose Work for Plinths 3

1971 -

Bruce McLean Study towards the Object of the Exercise

1978 -

Sir William Reid Dick Sketch for Virgin and Child

c.1939 -

Leonard McComb Portrait of Zarrin Kashi Overlooking Whitechapel High Street

1981 -

Henry Moore OM, CH Maquette for Standing Figure

1950, cast 1956 -

Sir Eduardo Paolozzi Standing Figure

1958