In Tate Liverpool

- Artist

- John Minton 1917–1957

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 947 × 760 mm

frame: 1167 × 981 × 103 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1987

- Reference

- T04887

Display caption

Minton was invalided out of the army in 1943, and from then until autumn 1946 he shared a London studio with two other painters, Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde. The Polish painter Jankel Adler also lived in the same house and he shared with the younger painters his knowledge of the European avant-garde, especially Picasso. The landscape in this painting is inspired by disused buildings seen near the sea at Marazion in Cornwall, but the children are probably invented figures. The subject of the painting may suggest an interest in child psychology and awakening sexuality, themes found in other work by Minton in the mid-1940s.

Gallery label, September 2004

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

T04887 Children by the Sea 1945

Oil on canvas 947 × 760 (37 1/4 × 29 7/8)

Inscribed ‘John Minton 1945’ t.l. and on a partly torn label on the back of the canvas ‘John Minton | Childre[...] | 35 gns | oil 30" × 4[...]’

Purchased from Guy Morrison Ltd (Grant-in-Aid) 1987

Prov: ...Michael Ayrton by 1946, no longer in his possession by 1947; ...; Leicester Galleries, 1959 bt by private collector; ...; Fine Art Society, 1979, by which sold to private collector July 1979; bt by Guy Morrison Ltd 1986

Exh: Four Young British Painters, Michael Ayrton, John Minton, William Scott, Keith Vaughan, AC tour, Doncaster Museum and Art Gallery, Aug.–Sept. 1946, Salisbury School of Art, Oct. 1946, Hanley Museum and Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent, Nov.–Dec. 1946, Guildford House, Guildford, Jan. 1947 (10, other venues not recorded); Artists of Fame and of Promise: Part Two, Leicester Galleries, Aug.–Sept. 1959 (122); Modern British Painters, Guy Morrison Ltd, Dec. 1986 (no catalogue); A Paradise Lost: The Neo-Romantic Imagination in Britain 1935–55, Barbican Art Gallery, May–July 1987 (186); When We Were Young: Children and Childhood in British Art, City Arts Centre, Edinburgh, July–Sept. 1989 (52, repr. in col.); John Minton: 1917–1957. A Selective Retrospective, Royal College of Art, Jan.–Feb. 1994, Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, March–April 1994, Oriel Mostyn, Llandudno, April–June 1994, Oriel 31, Davies Memorial Gallery, Newtown, June–July 1994 (7, repr. in col.)

Lit: Michael Ayrton, ‘Some Young British Contemporary Painters, in Orion, vol.3, Autumn 1946, p.86, repr. between pp.88 and 89; Tate Gallery Report 1986–88, 1988, p.73, repr. (col.); Frances Spalding, Dance Till the Stars Come Down: A Biography of John Minton, 1991, pp.80–1, 83, col. pl.vi between pp.180 and 181); William Joll, ‘Generous to a Fault: Review of “Dance Till the Stars Come Down” by Frances Spalding’, Spectator, 20 July 1991, p.33, repr. (col.); Frances Spalding, John Minton: 1917–1957. A Selective Retrospective, exh. cat., Oriel 31, Newtown 1993, pp.12, 59, repr. p.29 (col.)

This painting depicts two boys and an adolescent girl wandering in single file down a path by the sea. A girl in the foreground stands in front of a wall overgrown with gorse and moss. A delapidated building dominates the right of the picture. The path in the middle is protected from the sea by a wall. A tree bends over the path to form an arch with the building in the middle distance. Reds and greens are the predominant colours, with touches of acid yellow and white that emphasise details such as plants, stones, hair and cheekbones. The use of colour is not naturalistic.

Minton was invalided out of the army in 1943 and from then until autumn 1946 he shared a studio with Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde at 77 Bedford Gardens, Campden Hill, London. During this period he experimented in oils in order to develop his skills as a designer and draughtsman. In this new medium his lyrical romantic style became infused with a post-cubist idiom then practised by Colquhoun, MacBryde and their mentor, the Jewish-Polish artist Jankel Adler, who from 1943 occupied a studio in the same house. Adler had worked alongside Paul Klee at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art in the early 1930s and he inspired the younger artists with his knowledge of the European avant-garde, especially his understanding of Picasso's work.

The elliptical heads and schematised representation of clothing evident in ‘Children by the Sea’ appear in many of Minton's works of the late 1940s, and derive from Adler either directly or second-hand through Colquhoun and MacBryde (see Malcolm Yorke, The Spirit of Place: Nine Neo-Romantic Artists and their Times, 1989, p.177). In the early to mid-1940s Adler's oeuvre included pictures of girls, such as ‘The Irish Girl’, 1944 (repr.Jankel Adler, exh.cat., Stadtlische Kunsthalle, Düsseldorf 1985, [p.159], no.90), which resembles the girl in the foreground of T 04887. In 1942 Adler also painted ‘Orphans’, a schematised image of two small children (repr. ibid., [p.158], no.89 in col.). Lucian Freud, a friend of Minton at that time, also produced pictures of children with distorted features, for example, ‘Evacuee’, 1940 (repr. When We Were Young, exh. cat., City Art Centre, Edinburgh 1989, [p.68], no.60) and ‘Boy with a Pigeon’, 1944 (repr. Lucian Freud, exh. cat., Castello Sforzesco, Milan 1991, p.81, no.54 in col.). Adler was revered by Minton and two other artists, Benjamin Creme and Robert Frame. All three adopted aspects of his attitude to life, particularly his willingness to address human and social issues in his work (see Düsseldorf exh. cat., 1985, pp.202–27).

Between 1943 and 1946 Minton was teaching illustration at Camberwell School of Art. According to Frances Spalding, Minton's biographer, he made two visits to Cornwall during the summer holidays of 1944 and 1946 (Spalding 1991, pp.75, 83). However, a letter from Minton in Cornwall to Judith Hollman, a student of Minton's at Camberwell, appears to have been written in 1945. Minton writes (TGA 918.1.3):

This is from Cornwall: a high wind and blue sky so the caravan is rocked. I've been here a fortnight making detailed drawings of the landscapes: I discovered a disused tin-mine which is very interesting full of wheels and girders done in black line. I think it would be good for painting: besides this a lot of rather Sutherland attempts and the receding hills and spiked gorse on the lichened stone dykes... It seems remote, unreal, Camberwell and having to come back but I return in 8 days: I must try to make some paintings from these drawings, so back to London... you would like it here, for here one feels safe. To read of the atomic bomb is like a strange fiction from outside, here close to the sea, what could be more improbable?

His mention of the atomic bomb suggests that the letter was written after 6 August 1945, when an atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima signalling the close of the war in Asia.

During his visits to Cornwall he stayed with the Glasgow poet W.S. Graham at Wheelhouse in Pengersick Lane, Germoe, Marazion, which was, in fact, a caravan. Colquhoun and MacBryde had visited Graham there earlier. It has been suggested that details of the Cornish landscape appear in T04887 (letters to the compiler from Elizabeth Ayrton, 5 March 1987 and Rigby Graham, 22 March 1987). Judith Hollman believes that the building was probably Cornish as houses there were often in disrepair, although she agrees with Susan Einzig that the picture was almost certainly painted in Minton's studio in Bedford Gardens (conversation with the compiler, 24 October 1990 and letter from Susan Einzig to the compiler, 28 March 1987). Susan Einzig, who taught at Camberwell in the 1940s and became a close friend of the artist, suggests that the scene was put together from sketches of different subjects, of which the Cornish landscape was only one element. The building, for example, is similar to the blitzed buildings in Minton's earlier drawings of Poplar in East London. That the picture may have been painted in London is further suggested by the letter to Judith Hollman quoted above, which states his intention to produce paintings on his return.

In another letter to Judith Hollman from Cornwall (quoted in Spalding 1991, p.76, dated August 1944), written shortly before returning to London, Minton made several references to youth: ‘god how I love the land to stand and see it move in intricate perspective to the heat-haze of the gentle skyline, and there always the violence, the clear sharp violence of things living and growing and of being young walking the earth’ (TGA 918.1.4). He also reminded her of the line in the poem ‘The Old Vicarage, Grantchester’ by Rupert Brooke (1887–1915), ‘so gentle and english and full of being young’, and a quotation from Shakespeare's Cymbeline, ‘Golden lads and girls all must | As chimney-sweepers, come to dust’. On another occasion, Minton drew in ink a cartoon figure of a schoolboy wearing a cap and pullover on the front of an envelope in which he sent her a book on Leonardo da Vinci (TGA 918.1.5). The boy's hands are in the air and he grins, standing rather ludicrously beside the stamp, as if in greeting. This cartoon figure is similar to the boy depicted in the foreground of T04887.

The figures depicted in T04887 are presumably invented. The boys' caps and jackets suggest school uniform but it is unlikely that they would have been wearing such attire during the summer holidays. There is no evidence to support the view that the children are evacuees, although this would correlate with Minton's perception of Cornwall as a haven, safe from destruction and threat.

In the first quoted letter to Judith Hollman, Minton refers to ‘Sutherland attempts’. Minton had admired Graham Sutherland's work since before the war. He experimented with Sutherland's visual language during the early 1940s, incorporating certain stylistic elements into his pictures. The composition of ‘Children by the Sea’ is structured with crescents and ovoid shapes of colour outlined with black. This type of compositional structure was developed by Sutherland in the mid-1930s, and epitomised in ‘Entrance to a Lane’, 1939 (N06190). This particular work was then in the collection of Peter Watson (1908/9–56), patron of artists and poets and founder of Horizon (1940–50), and was known to Minton and many of his peers. Minton, John Craxton, and Michael Ayrton produced their own versions of this painting (see Virginia Button, ‘The Aesthetic of Decline: English Neo-Romanticism c.1935–1956’, unpublished PhD thesis, London University, 1991, p.192). In 1945 Sutherland had begun a group of ‘Thorn Tree’ paintings during a visit to Pembrokeshire, some of which were exhibited for the first time in Paris in November 1945 (see, for example, ‘Thorn Tree’, repr. Graham Sutherland, exh. cat., Tate Gallery 1982, p.108, no.24). The head of the girl in the foreground of T04887 is framed by sprigs of spiky gorse, which may indicate that Minton was aware of these pictures before their public showing.

The two known preparatory studies for ‘Children by the Sea’ belonged at one time to Judith Hollman. One was an oil painting, about three quarters the scale of T04887 (sold by the owner in 1961, whereabouts unknown) and the other, an ink drawing with white watercolour (repr. Spalding 1991, pl.9 between pp.52 and 53), is still in her possession. This drawing may have been a final study for one of the oil paintings. Although its composition is similar to that of T04887, it differs in detail. The background at the left, for example, shows an open sea with a jetty. In addition to the four figures depicted in T04887, there are also two figures placed behind the girl in the middle distance and a third shadowy figure behind the boy furthest from the viewer. In the drawing the girl in the foreground has a harsh expression and plays with her fingers, whereas in T04887 her expression has softened and her hands toy with her hair. Furthermore, in the drawing the boy on the left wears a polo neck jumper and does not have a cap. His hands are awkwardly stuffed into his pockets, creating a tense atmosphere. This sense of anticipation is retained in T04887, although here the adolescent girl seems demure rather than petulant and the boy seems more detached in mood. Frances Spalding has noted that in Minton's drawing the boy is more isolated from the other children.

The subject of the painting suggests an interest in child psychology and awakening sexuality. Minton's preoccupation with these themes is evident in a number of other works he produced in the mid-1940s. The 1946 Arts Council exhibition included T04887 and Minton's ‘The Glasgow Children’, 1945, later known as ‘Children of the Gorbals’ (repr. Frances Spalding, John Minton, exh. cat., Oriel 31, 1993, p.30, no.47 in col.), which became one of his best known paintings. This and ‘Children Playing Games’ (repr. ibid., p.51 no.8 in col.), also of 1945, are similar in style and subject to T04887, except that they are both set in an urban street. In all three paintings the children, drawn with the same exaggerated elliptical heads, appear to be waiting for something to happen. There is a crowd in the ‘Children of the Gorbals’, but in the other two pictures a boy and girl are prominent in the foreground. In ‘Children Playing Games’ the girl is talking to a reluctant looking boy, and in T04887 the girl in the foreground appears to be awaiting or provoking an approach from the boy.

Focusing on the interaction between the sexes, ‘Children by the Sea’ and ‘Children Playing Games’ also relate to Minton's earlier depictions of couples, such as ‘London Street’, 1941 (repr. Spalding 1991, pl.4 between pp.52–3) in which a girl and youth stand in a desolate urban environment. A similar work, ‘North Country Industrial Town’, 1946 (repr. Penguin New Writing, no.28, 1948, p.96 as ‘Street Scene in Industrial City’) is more explicit in its representation of a romantic view of love: a couple cling together in a deserted urban landscape, the tall youth protecting his sweetheart.

Frances Spalding has suggested that Minton's pictures of children are possibly the result of exploring memories of his own lonely childhood. The 1920s and 1930s witnessed the popularisation of psychology as a science and, in particular, the analysis of child development. During the 1940s a welfare state ethos helped to further public interest in childcare and behaviour. One aspect of this subject, youth delinquency, was of particular interest to Minton. Later, in the 1950s, he strongly identified with popular role models of ‘alienated rebellion’ such as the actors Montgomery Clift and James Dean (see David Mellor, A Paradise Lost: The Neo-Romantic Imagination in Britain 1935–1955, exh. cat., Barbican Art Gallery 1987, p.64). Minton indentified with Clift who, like himself, was homosexual and suffered the same inability to find a worthy partner (see T.H.G. Ward, ‘John Minton and Montgomery Clift’, London Magazine, April/May 1980, pp.47–55).

Frances Spalding reports that in an article of 1946, ‘Some Young British Contemporary Painters’ (in Orion, vol.3), Michael Ayrton praised Minton's recent work. ‘Children by the Sea’, at that time in Ayrton's possession, was reproduced in the article alongside Robert Colquhoun's ‘Woman with a Birdcage’. MacBryde wrote an angry riposte to this juxtaposition, which he thought vulgar owing to the ‘ill-digested influences’ and ‘technical tricks’ characteristic of Minton's work compared with the ‘integrity and majesty’ of ‘Woman with a Birdcage’. For Spalding this outburst suggests an element of jealousy because in her view ‘Children by the Sea’ was a strong painting: ‘For though various influences are clearly discernible in Minton's “Children by the Sea”, they are swept into a convincing whole where the flow of movement from one area to the next is matched by the sumptuously rich colour. It remains one of Minton's most haunting pictures’ (Spalding 1991, p.83).

In a letter to the compiler dated 5 March 1987 Elisabeth Ayrton wrote that Minton probably gave this painting to her husband directly from his studio. Michael Ayrton often exchanged work with his artist friends, although Mrs Ayrton had no record of this particular exchange. She added, ‘It is just possible that Michael bought the painting from Minton if Minton was short of money at that time, but unlikely, as he was always short of money himself. I can't imagine, however, that if it was a gift-exchange he would have sold it at any time before Minton's death’. When she first met Ayrton in 1947 the picture was no longer in his possession.

Published in:

Tate Gallery: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions 1986-88, London 1996

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- hat, cap(336)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- standing(3,106)

- group(4,227)

- UK cities, towns and villages(12,725)

-

- Marazion(3)

- Cornwall(1,034)

- England(19,202)

- England, South West(3,507)

- England, Southern(8,982)

- birth to death(1,472)

-

- youth(193)

You might like

-

Paul Nash Totes Meer (Dead Sea)

1940–1 -

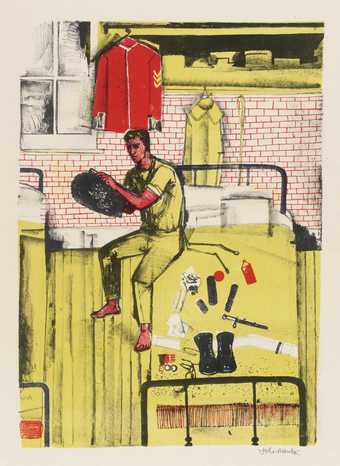

John Minton Horseguards in their Dressing Rooms at Whitehall

1953 -

Roger Mayne Girls swinging on a rope, Southam Street

1951 -

Keith Vaughan Small Assembly of Figures

1951 -

John Craxton Hotel by the Sea

1946 -

John Minton Composition: The Death of James Dean

1957 -

John Minton Portuguese Cannon, Mazagan, Morocco

1953 -

John Minton Street and Railway Bridge

1946 -

John Minton Corte, Corsica

1947 -

Patrick Heron Harbour Window with Two Figures : St Ives : July 1950

1950 -

John Craxton Pastoral for P.W.

1948 -

Gerald Wilde Fata Morgana

1949 -

John Minton Landscape at Les Baux

1939 -

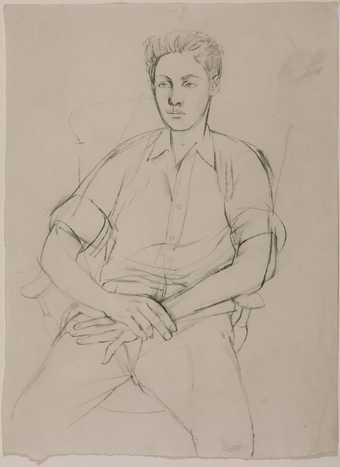

John Minton Portrait of Kevin Maybury

1956 -

John Minton Portrait of a Boy (?)

c.1948