On loan

Guggenheim Museum (Bilbao, Spain): Joan Miro, Absolut Reality, The Paris Years

- Artist

- Joan Miró 1893–1983

- Original title

- Peinture

- Medium

- Tempera and oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 972 × 1302 mm

frame: 1080 × 1418 × 68 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1971

- Reference

- T01318

Summary

Painting is a large canvas in landscape format dominated by a highly saturated cerulean blue ground painted in tempera. Over this luminous monochrome surface are arranged several delicately irregular forms. The most prominent of these is an amorphous white shape floating on the left, painted in patchy brushstrokes that allow glimpses of the blue beneath. Sinuous black lines and smaller organic shapes in touches of black, red, green, yellow and brown hover between abstraction and poetic suggestions of sexual organs: breast-like forms appear in the upper centre and lower right, and the nipple of the latter is almost enclosed by a dark brown patch. On the right, small circles with lines dangling from them may suggest airborne balloons.

Painting is one of a large series of works made by Miró between 1924 and 1927 which are often referred to as ‘automatic paintings’ (Simon Wilson, Surrealist Painting, London 1975, p.5), ‘dream paintings’ (Dupin 1962, p.157) or ‘peinture-poesie’ (poetry-painting) (Lanchner 1993, p.15). With their fields of colour animated by semi-abstract symbols, they represented a marked departure from the figurative style of Miró’s earlier work.

In the 1920s, Miró was dividing his time between his native Catalonia and Paris, where he became closely associated with avant-garde figures in art and literature, including members of the emerging surrealist movement. Writer André Breton was among those interested in using art to reveal the secrets of the unconscious mind, and his 1924 Surrealist Manifesto famously advocated the practice of ‘psychic automatism in its pure state’ (André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, Ann Arbor 1972, p.26). Perhaps influenced by this contemporary interest in relinquishing artistic control, Miró often described his working method as highly spontaneous. He recalled in 1948 that he was inspired at the time by hunger-induced hallucinations, and that he allowed his compositions to be directed by chance and by the movements of his paintbrush (Joan Miró, Selected Writings and Interviews, ed. by Margit Rowell, London 1987, pp.208–11). Subsequent research suggests a more deliberate approach: the Miró Foundation in Barcelona holds notebooks containing many preparatory drawings from this period (Gaëtan Picon (ed.), Joan Miró: Catalan Notebooks, London 1977, p.7). Although the details of Painting are painted in oil, the water-based blue paint chosen for the background appears in other works of 1927 and may have been the same product commonly used to paint houses in Spain and Portugal.

Miró explained in 1948 that ‘for me a form is never something abstract; it is always a sign of something’ (Miró 1987, p.207), and scholars have speculated as to the meaning of the enigmatic imagery in Painting. Although reluctant in general to describe the meaning of his works, he identified the white figure at the left as a horse in December 1977 to Sir Roland Penrose. This may connect Painting to a group of thirteen other works made in 1927 that relate to the theme of the circus horse (see Dupin 1962, p.517). Many of these – such as Circus Horse 1927 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) – share its bright blue background, white figure and long, curving lines, resembling a horse directed by a ringmaster and his whip. Margit Rowell, meanwhile, has drawn attention to Miró’s fascination with experimental literature, and proposed a 1917 play by poet Guillaume Apollinaire, Les Mamelles de Tirésias (The Breasts of Tirésias), as a source for the painting’s apparent allusions to strings, balloons and procreation (see Ronald Alley, Catalogue of the Tate Gallery’s Collection of Modern Art other than Works by British Artists, Tate Gallery and Sotheby Parke-Bernet, London 1981, pp.524–5). A horseback figure also appears in Apollinaire’s text, and Miró may have had multiple references in mind. A label on the back of Painting reads ‘Fantaisie bleue’ (‘Blue Fantasy’), but a letter of March 1973 confirms that it should be known simply as Painting.

American critic Clement Greenberg was among those who considered this period of Miró’s work notable primarily for its formal innovations (Clement Greenberg, Joan Miró, New York 1948, p.26), and many have pointed to the affinities between his flat fields of colour and later abstract expressionist painting. Others praised these dreamlike canvases for their ‘mysterious forms relating to the basic processes of life – especially procreation – to the cosmos and to the archetypal world’ (Wilson 1975, p.6). Painting was previously owned by the artist’s friend Tristan Tzara, a dada poet who explored principles of automatism in his own writing.

Further reading

Jacques Dupin, Joan Miró: Life and Work, London 1962, no.219, reproduced p.518.

Carolyn Lanchner, Joan Miró, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1993.

Jacques Dupin and Ariane Lelong-Mainhaud, Joan Miró: Catalogue Raisonné: Paintings, Volume I: 1908–1930, Paris 1999, no.243, reproduced p.184.

Hilary Floe

April 2016

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Delicate linear forms float on the open blue that Miró associated with dreams. With André Masson, Miró was the first to create imagery using automatic techniques in which forms seemed to emerge directly from the unconscious. From this he developed his own personal sign language, which simplified familiar things such as stars, birds and parts of the body. He later revealed, for example, that the white shape in this painting signified a horse.

Gallery label, October 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Joan Miró born 1893 [ - 1983]

T01318 Peinture

(Painting) 1927

Inscribed 'Joan Miró | 1927' on back of canvas

Water-soluble background and motifs in oil, on canvas, 38 1/4 x 51 1/4 (97 x 130)

Purchased from the Galerie Beyeler (Grant-in-Aid) with the aid of the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1971

Prov:

With Galerie Pierre, Paris (purchased from the artist); Tristan Tzara, Paris; Christophe Tzara, Sceaux; sold by him at Sotheby's, London, 30 April 1969, lot 101, repr. in colour; bt. Galerie Beyeler, Basle

Exh:

Joan Miró, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris, June-November 1962 (48) as 'Peinture'; Moon and Space, Galerie Beyeler, Basle, January-February 1970 (54, repr. in colour) as 'Fantaisie bleue'

Lit: Jacques Dupin, Joan Miró: Life and Work

(London 1962), No.219, p.518 repr.; exh. catalogue Joan Miró: Magnetic Fields, Guggenheim Museum, New York, October 1972-January 1973

Repr:

Jacques Lassaigne, Miró

(Lausanne 1963), p.51 in colour; Simon Wilson, Surrealist Painting

(London 1975), pl.43 in colour

There is a label on the back with the title 'Fantaisie bleue', but Miró wrote to the compiler in March 1973 that this work has no title and should be known simply as 'Peinture'.

Many of Miró's paintings of the period 1924 to 1927 have broad fields of colour animated by enigmatic signs, and sometimes even by words. Margit Rowell has shown in the catalogue of the Guggenheim Museum's Miró exhibition that his work of this period was strongly influenced by poetry. Miró is known to have steeped himself in poetry in the 1920s, and through his friendship with Masson met practically all the leading French poets of the time. Though he has always been reluctant to discuss and identify the imagery in these pictures, Margit Rowell has discovered a number of instances in which his paintings of the period can be related to works by Rimbaud, Jarry, Apollinaire, Saint-Pol-Roux, Desnos and others, including some in which there is such a close correspondence to the poetic images in a specific poem as to give the impression that he was illustrating that poem.

In this case one possible source may have been Apollinaire's play Les Mamelles de Tirésias, first performed in June 1917, which Apollinaire termed a 'drame surréaliste' - the first use of the word 'surrealist'. At the beginning of the play, the wife Thérèse announces that she is tired of being a woman and doesn't want to have babies; she wants to be a soldier, a doctor, a minister in the government, a philosopher, a chemist and so on. Then she says that she is beginning to undergo physical changes: 'My beard is growing, my bosom is coming away' (... la barbe me pousse | Ma poitrine se détache). She utters a loud cry and half opens her blouse from which her breasts come out in the form of children's balloons, one red, the other blue; as she releases them, they float upwards but remain attached to her by strings. She pulls on the strings and makes the balloons dance, then bursts them. Next she takes balls out of her corsage and throws them at the audience, then strokes her beard and her moustache, which is also beginning to grow, saying 'I am like a field of corn ready for a mechanical reaper' (J'ai l'air d'un champ de blé qui attend la moissonneuse mécanique). After announcing that she wants to be known henceforth by the masculine name Tirésias, she makes her husband put on her clothes. He becomes a man-woman and says that he will solve the need for repopulation by producing babies on his own.

By the beginning of the second act he has managed to produce no fewer than 40,049 babies in a single day and there are numerous cradles on the stage, with the sound of babies crying. Eventually his wife re-emerges from disguise and greets her husband affectionately again. He says 'You can't go on being as flat as a bug' (... il ne faut plus | Que tu sois plate comme une punaise), and hands her a bunch of balloons and a basket of balls. She releases the balloons and throws the balls at the audience, and the play ends with her saying 'Fly away birds of my feebleness, go and feed all the children of the repopulation' (Envolez-vous oiseaux de ma faiblesse | Allez nourrir tous les enfants | De la repopulation).

On the right of the picture is a breast with what seems to be a balloon beside it. Just below the nipple is a brown patch which could have been suggested by the beard and is shaped like a sheaf of corn. Above the balloon is a black dot with lines streaming from it which is possibly either a ball in flight or a balloon rising or bursting. At the top of the picture hovers what seems to be a breast-balloon.

On the other hand the white shape on the left was identified by Miró in December 1977 as a horse (information from Sir Roland Penrose), and the picture is therefore probably also related to the series of paintings of circus themes dated 1927 which is known as the Circus Horse. A combination of different themes like this would be quite in accord with his practice.

The background appears to have been painted with the kind of water-soluble blue paint that is frequently used on the outsides of houses in Spain and Portugal. It was also used in other paintings of the same year, such as 'Personage; The Brothers Fratellini' in the Lydia and Harry Lewis Winston collection (Dr and Mrs Barnett Malbin, New York).

(The compiler owes the suggestion that this picture was influenced by Les Mamelles de Tirésias

to Margit Rowell).

Published in:

Ronald Alley, Catalogue of the Tate Gallery's Collection of Modern Art other than Works by British Artists, Tate Gallery and Sotheby Parke-Bernet, London 1981, pp.524-5, reproduced p.524

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- figure(2,270)

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- colour(2,481)

- music and entertainment(2,331)

-

- circus(105)

- agriculture, gardening & fishing(951)

-

- whip(45)

- ball(50)

- breast(103)

- sexual organs(178)

- womb(31)

- birth to death(1,472)

-

- breast feeding(19)

You might like

-

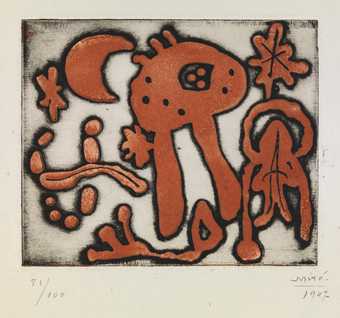

Joan Miró Women and Bird in the Moonlight

1949 -

Joan Miró Composition

1947 -

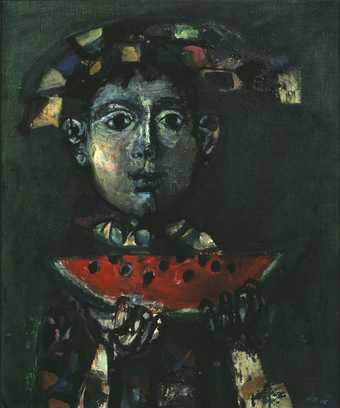

Antoni Clavé Child with a Water-Melon

c.1947–8 -

Antoni Tapies Grey and Green Painting

1957 -

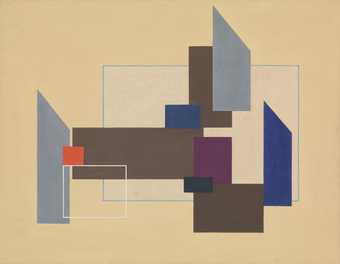

John Cecil Stephenson Painting

1937 -

Arthur Jackson Painting

1937 -

Rodrigo Moynihan Painting

1935 -

Salvador Dalí Autumnal Cannibalism

1936 -

Salvador Dalí Mountain Lake

1938 -

Salvador Dalí Metamorphosis of Narcissus

1937 -

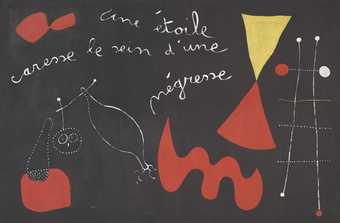

Joan Miró A Star Caresses the Breast of a Negress (Painting Poem)

1938 -

Joan Miró Message from a Friend

1964 -

Edgar Hubert Painting

1935–6 -

Joan Miró Head of a Catalan Peasant

1925 -

Francis Picabia Otaïti

1930