Not on display

- Artist

- Chris Ofili CBE born 1968

- Medium

- Polyester

- Dimensions

- Object: 1445 × 2590 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the artist 2016

- Reference

- T14773

Summary

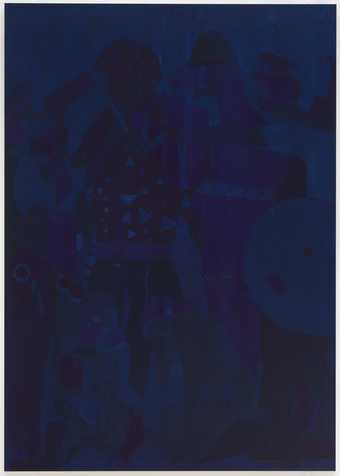

Union Black 2003 is Chris Ofili’s red, black and green version of the British ‘Union Jack’ flag. In it the artist altered the colours of the traditional Union flag so that the red cross of St George is black, the white saltire of St Andrew is green and the red saltire of St Patrick is black; the background of Ofili’s flag is red. His colours derive from the Pan-African tricolour that the American Black nationalist Marcus Garvey suggested for the United Negro Improvement Association political movement of the 1920s – red, green and black representing African blood, natural resources and skin. Union Black comes from a period in Ofili’s work when he focused on a series of red, black and green paintings (collectively titled Within Reach) around the theme of Black love and liberation. These were exhibited in the British Pavilion at the 50th Venice Biennale in 2003; outside the pavilion three large and three small versions of the flag were presented for the first time. The artist also choose to fly Union Black over the Millbank entrance of Tate Britain during his solo exhibition there in 2008.

Ofili’s shifting of the registers of a national emblem and the sites and contexts in which it is displayed has precedents in the American artist David Hammons’ (born 1943) U.N.I.A. Flag 1990 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), a similarly doctored version of the stars and stripes of the United States. It also relates to the title of British historian Paul Gilroy’s book, There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack (1987). Like these, Union Black references and deconstructs ideas about collective memory, boundaries and the meaning of allegiance to a nation. Curator Okwui Enwezor has written of Ofili’s red, black and green works:

Within Reach played with the myth-making machineries – flag, ethnicity, language, culture, identity, modernity – of the nation state as simultaneously belonging to an autochthonous past and a modern present … emphasis[ing] discontinuity in the flow of discourse by which the nation is narrated and made visible to its multiple communities, calling into question the stability of the nation’s collective memory and its official allegory.

(Okwui Enwezor, ‘Shattering the Mirror of Tradition: Chris Ofili’s Triumph of Painting at the 50th Venice Biennale’, in Becker, Adjaye, Enwezor et al. 2009, p.146.)

As in the artist’s earlier work from the 1990s, which employed materials and imagery with racial implications (including elephant dung, characters from Blaxploitation films and hip hop music), Union Black is a continuation of Ofili’s meditation on race and visibility, and introduces the questions of identity and displacement with which his work has engaged further since his move from London to Trinidad in 2005.

The use of a restricted palette is a recurring feature within Ofili’s practice, as is a feeling for colour on an emotional and physical level as well as a political and ideological one. Speaking to the curator Thelma Golden about how his red, black and green series can be seen in relation to the mixture of intellect and intuition in jazz music, Ofili explained:

I was trying to push the red as far as it needed to go in certain areas before it needed to flip to a green. It’s a bit like when you are listening to a great harp solo in an Alice Coltrane track, where the strings are really gliding along through the track, and then Pharaoh Sanders might play a horn that kind of interrupts things, and then it falls back into the harp. In a way, what I’m trying to say is that it’s about a feeling for a colour, rather than what the colour might necessarily represent.

(Quoted in ‘Chris Ofili and Thelma Golden: A Conversation’, in British Council 2003, n.p.)

Prior to the conception of Union Black and the black, red and green series of paintings, Ofili had used the same colour palette in Black Paranoia 1997 (private collection) to explore the subject of Black identity, modernism and modernity. His landmark installation The Upper Room 1999–2002 (Tate T11925) comprises twelve paintings of Rhesus monkeys, each in a monochrome palette, presented with extraordinary sensory effect. Since his move to Trinidad, Ofili has worked intensively with the colour blue in order to capture the feeling and sense of the night there.

Further reading

Chris Ofili: Within Reach, exhibition catalogue for the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, British Council, London 2003.

Carol Becker, David Adjaye, Okwui Enwezor et al., Chris Ofili, New York 2009.

Massimiliano Gioni (ed.), Chris Ofili: Night and Day, exhibition catalogue, New Museum, New York 2014.

Helen Little

July 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Ofili’s artwork applies the red, green and black of the Pan-African tricolour to the national emblem of Great Britain. Pan-Africanism highlights the shared history of people of African descent and encourages global solidarity. In 1920, Jamaican American Black nationalist Marcus Garvey noted the symbolism of these colours, ‘red representing the noble blood that unites all people of African ancestry, the colour black for the people, green for the rich land of Africa’. In applying these colours to the Union Jack, Ofili creates a flag that recognises and celebrates Black Britain.

Gallery label, January 2022

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- memory(367)

- universal concepts(6,387)

-

- history(1,983)

- music and entertainment(2,331)

-

- music, jazz(7)

- religious and ceremonial(1,733)

- government and politics(3,355)

-

- Black Power(4)

- colonialism(429)

- displacement(24)

- freedom(183)

- migration(20)

- race(381)

- nature(43)

-

- nature - green(11)

- blood - red(1)

- skin - black(1)

You might like

-

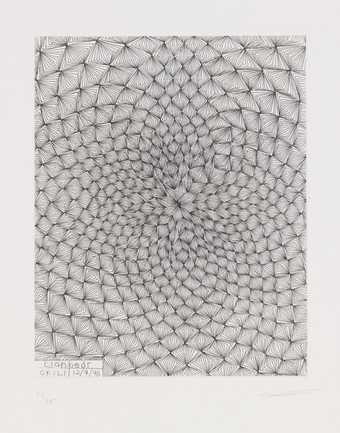

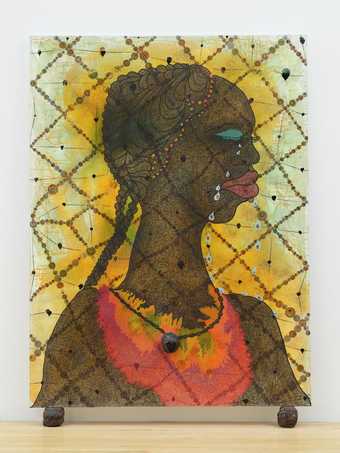

Chris Ofili CBE Black Shunga

2008–15 -

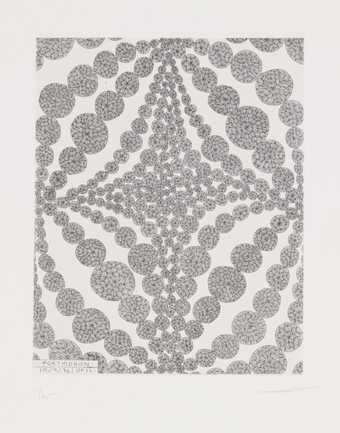

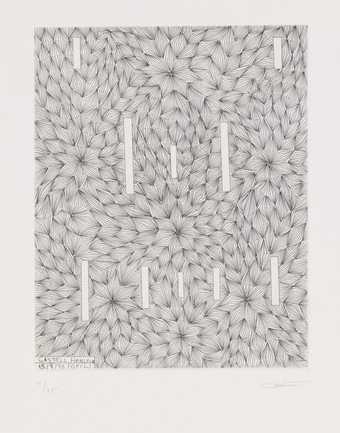

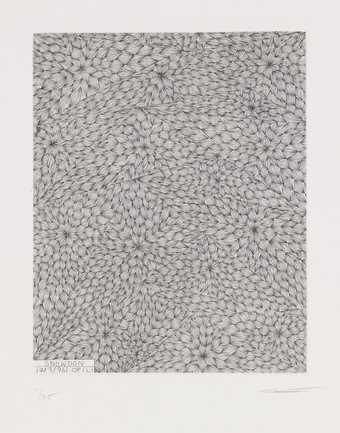

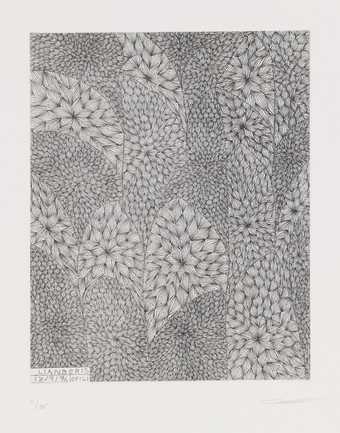

Chris Ofili CBE Portmerion 10.9.96

1996 -

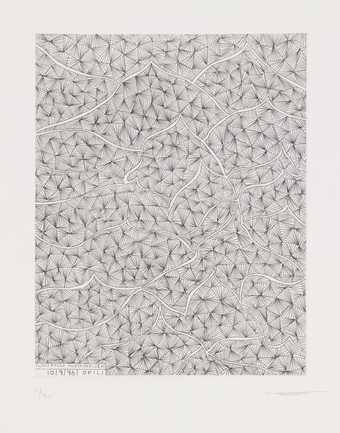

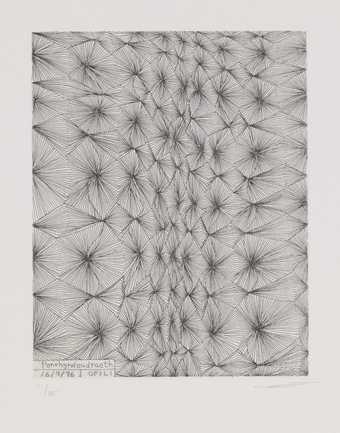

Chris Ofili CBE Twynitywod Morfa Harlech 10.9.96

1996 -

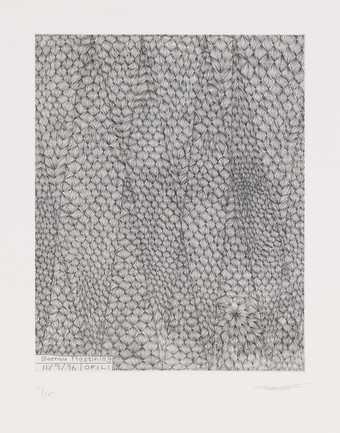

Chris Ofili CBE Blaenau Ffestiniog 11.9.96

1996 -

Chris Ofili CBE Llanbedr 12.9.96

1996 -

Chris Ofili CBE Portmadog 14.9.96

1996 -

Chris Ofili CBE Castell Harlech 15.9.96

1996 -

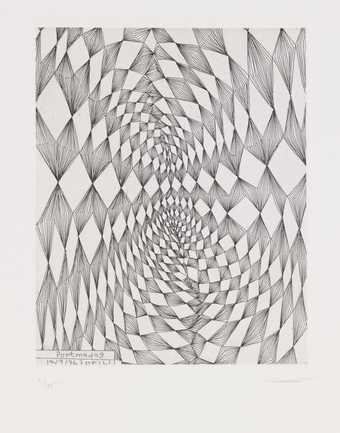

Chris Ofili CBE Penrhyndeudraeth 16.9.96

1996 -

Chris Ofili CBE Snowdon 17.9.96

1996 -

Chris Ofili CBE Llanberis 17.9.96

1996 -

Chris Ofili CBE Double Captain Shit and the Legend of the Black Stars

1997 -

Chris Ofili CBE No Woman, No Cry

1998 -

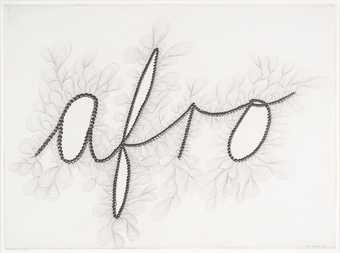

Chris Ofili CBE afro

2000 -

Chris Ofili CBE The Upper Room

1999–2002 -

Chris Ofili CBE Blue Devils

2014