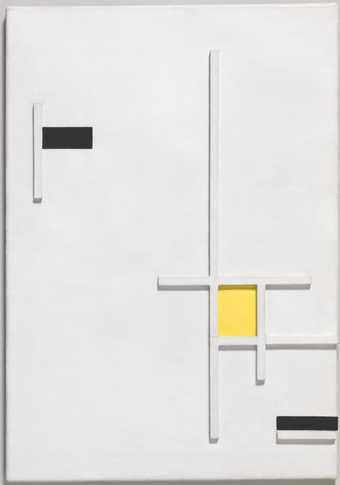

Marlow Moss

Composition in Yellow, Black and White

(1949)

Tate

A line has no gender. Neither does shape or colour. Gender does not reside in a hairstyle, a name or even a body. And yet, the human social world continues to persuade us that people, clothes, colours and even works of art are either ‘feminine’, ‘masculine’ or a blend of the two. Each choice we make about how we look or act, what we wear or create, is assigned a gendered reading under this polarising doctrine.

Marlow Moss trod a defiant course through this territory. The adopted first name, which the artist preferred to use without a title, seems to dodge gender associations. With fastidiously cropped hair, Moss dressed in a style that appeared to some as manly, others as butch or perhaps androgynous. People often took Moss to be male, but records suggest that intimates, including life-partner Netty Nijhoff, referred to the artist with female pronouns. Any attempt to position Moss’s gender focuses attention on how slippery such clues are – and all the more so in the past.

And then there is the work. After moving to Paris in 1927, Moss became wedded to a severe, geometric strand of non-objective painting, to an extent unmatched by any British contemporary. Straight lines, primary colours and black rectangles are not actually ‘masculine’, any more than Marie Laurencin’s sploshy pastels are ‘feminine’, but that hasn’t stopped critics, past and present, from positioning either style on a spectrum of gender. Is it legitimate to wonder whether Moss consciously ‘wore’ hard-edged abstraction – much like the favoured tailored jackets, cravats and jodhpurs – as a strategy to disrupt the gender first assigned to the artist?

This text is an extract from A Queer Little History of Art, written by Alex Pilcher.