Not on display

- Artist

- Paula Rego 1935 – 2022

- Medium

- Acrylic paint on paper on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 2126 × 2740 mm

frame: 2280 × 2890 × 80 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1989

- Reference

- T05534

Summary

The Dance 1988 is a large painting featuring eight figures dancing in the foreground on a moon-lit beach. The figures include a group of three women of varying ages moving in a circle holding hands, two dancing couples (including one woman who seems to be pregnant), and a woman stood alone on the left-hand side of the composition. In the background on the right-hand side of the painting is a large, steep and craggy cliff, on top of which stands an imposing fortress-like structure, depicted in silhouette against a deep blue sky filled with inky clouds and a full moon. The work has a dream-like quality, heightened by its night-time setting, the lengthy shadows cast by the figures, and by Rego’s unusual use of scale, with the woman on her own appearing to be much larger than the figures alongside her.

The Dance, which at the time it was made was the largest painting the Portuguese-born British artist Paula Rego had created, was completed in London, where Rego moved permanently in 1976. Rego has claimed that the idea to ‘paint people dancing’ was suggested by her husband, the artist Victor Willing (1928–1988), who died shortly before The Dance was completed (quoted in Tate Liverpool 1997, p.127). Rego has also claimed that Willing suggested adding male figures to the painting, which she then based on her son Nicholas (who sat for her) and on a photograph of her husband (quoted in Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, p.255).

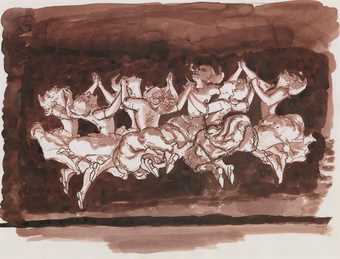

The development of the composition of The Dance is recorded in eleven preparatory drawings in ink that Rego donated to Tate when the painting was acquired in 1989. These drawings show various combinations of dancing figures, from seven young women jubilantly jumping in the air (Tate T05541) to a mixed group strolling along a beach (Tate T05545), which is much closer to the final painting.

The Dance was planned to be the last painting in an exhibition of Rego’s work at the Serpentine Gallery in London, alongside other works completed at this time such as Departure 1988 (which was destroyed in a warehouse fire in east London in 2004) and The Family 1988. Rego has explained, ‘It was to have been the picture that would tie everything together, hung over the top of everything else’ (quoted in Fiona Bradley, Paula Rego, London 2002, p.42). However, The Dance was not completed in time for the show, which opened in October 1988.

Many of Rego’s paintings seem to suggest mysterious narratives, frequently evoking childhood memories, family scenes, fairy tales and myths. The figures in The Dance may be seen in symbolic terms, as the curator Fiona Bradley has argued:

Often interpreted autobiographically, [The Dance] plays out the ways in which a woman – the main character, larger than the others, to the left of the painting – may structure her conception of herself. The woman stands apart from the dancers, in a separate narrative and compositional space. As she looks at the viewer a variety of ways of being a woman play across the picture’s surface. The three at the back form a matriarchal hierarchy, a happy triumvirate of child, mother, grandmother; a complete cycle of femininity. The other two define themselves in relation to their men – one courting, the other pregnant.

(Fiona Bradley, ‘Introduction: Automatic Narrative’, in Tate Liverpool 1997, p.19)

While the critic John McEwen has claimed that The Dance is ‘wholeheartedly nostalgic, with no sense of menace or subversion’ (John McEwen, Paula Rego, London 2006, p.168), Maria Manuel Lisboa, a specialist in Portuguese culture, has suggested that the shadowy structure in the top right-hand corner of the painting resembles a military fort on the Estoril coast in Caxias, situated five miles west of Lisbon, where Rego was born (Lisboa 2003, p.73). This fort was used as a prison and torture site during the Estado Novo (1933–74), a period of authoritarian rule in Portugal, principally led by António de Oliveira Salazar, who was Prime Minister from 1932 to 1968. The presence behind the dancers of this dark and oppressive building, closely associated with the violence of the Salazar regime, might be seen to add a sinister edge to the scene.

Further reading

Paula Rego, exhibition catalogue, Tate Liverpool, London 1997, pp.19, 127–32, reproduced p.131.

Maria Manuel Lisboa, Paula Rego’s Map of Memory: National and Sexual Politics, Aldershot 2003, pp.71–4, reproduced p.72.

Paula Rego, exhibition catalogue, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid 2007, pp.50, 255, reproduced p.93.

Amy Tobin

February 2014

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

During the 1980s Rego created paintings inspired by her early life in Portugal. While the scene here could represent a memory of folk festivals or 'festas', it also has a more profound symbolic meaning. The dance can be read as a dance of life, representing the stages from a girl's childhood to old age. The rhythmic movement of the figures contrasts with the stillness of the setting, suggesting the balance between perpetual change and the essential continuity of existence. Rego's painting has an eerie, dream-like quality typical of her work, which often refers to childhood fears and fantasy. The work can be considered a memorial to Rego's husband, the artist Victor Willing, who died during its completion.

Gallery label, August 2004

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Technique and condition

Painted in artists' acrylic colour on paper previously adhered to a cotton canvas by the artist's framer. The canvas is now stapled by its edges to a stretcher.

The initial paint applications to establish tone were carried out using well diluted washes in colours including a dull pink and brown. Equally fluid drawing of the outlines of the principal forms was done in black paint. Subsequent applications tend to be in thicker paint, many of them being carried up to, but leaving visible, the black brushed outlines. The white colour of the paper support provided luminosity to those areas of the paint which remain thin. The artist has added acrylic medium to enrich some colours but has not applied a general film of protective varnish.

The numerous small pinholes in paper and canvas were occasioned during the painting process. The varying degrees of wrinkling which affect paper and canvas tend to reflect the amount of time the artist worked on a given area, and the amount of water and water-borne medium that was absorbed from the paint.

Peter Booth

1994

Features

Explore

- architecture(30,960)

-

- townscapes / man-made features(21,603)

-

- building - non-specific(3,161)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

- music and entertainment(2,331)

-

- dance(296)

- girl(1,079)

- dreaming(213)

- countries and continents(17,390)

-

- Portugal(64)

- birth to death(1,472)

-

- childhood(42)

- couple(1,322)

You might like

-

Paula Rego Doctor Dog

1982 -

Paula Rego Whinney Moor

1996 -

Paula Rego Mist III

1996 -

Paula Rego Nanny, Small Bears and Bogeyman

1982 -

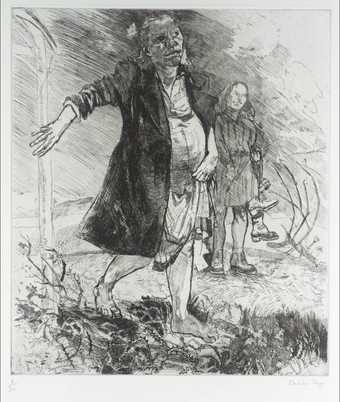

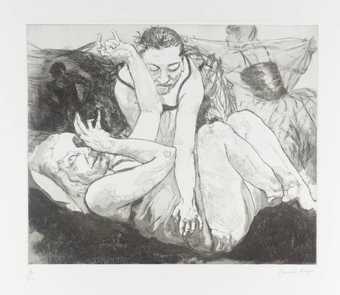

Paula Rego Drawing for ‘The Dance’

1988 -

Paula Rego Drawing for ‘The Dance’

1988 -

Paula Rego Drawing for ‘The Dance’

1988 -

Paula Rego Drawing for ‘The Dance’

1988 -

Paula Rego Drawing for ‘The Dance’

1988 -

Paula Rego Drawing for ‘The Dance’

1988 -

Paula Rego Drawing for ‘The Dance’

1988 -

Paula Rego Drawing for ‘The Dance’

1988 -

Paula Rego Drawing for ‘The Dance’

1988 -

Paula Rego Drawing for ‘The Dance’

1988 -

Paula Rego The Firemen of Alijo

1966