In Tate Modern

- Artist

- Albert Renger-Patzsch 1897–1966

- Part of

- Group of vintage prints

- Original title

- Hörder Verein - Kohlenmischlanlage (Dortmund)

- Medium

- Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

- Dimensions

- Image: 222 × 166 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by the Photography Acquisitions Committee 2011

- Reference

- P79952

Summary

Hörder Verein – Coal Mixing Plant (Dortmund) is a black and white photograph picturing the exterior of a mixing plant in which coal was sorted and cleaned. Like the majority of Renger-Patzsch’s photographs of industrial settings, the scene in this image is deserted, devoid of workers, with the focus falling on the isolated industrial structure that dominates the composition. Shot from a low angle, the perspective lends the plant an air of monumentality. Tight framing focuses attention on other details within the frame: at the foot of the plant a row of circular machines stretches into the distance, beneath which lie piles of rocks and coal in a variety of tones. Rendered clearly and sharply, these details become so insistent as to form an ‘inner’ composition within the image (Donald Kuspit, Albert Renger-Patzsch: Joy Before the Object, New York 1993, p.69). Renger-Patzsch used photography to isolate, frame and focus attention on details of the material world. By supplementing human vision in this way, his photographs encourage the viewer to ‘look at things from a new vantage point’ and take increased ‘joy’ in seeing the world of objects anew (Renger-Patzsch 1928, p.647).

The title identifies the location of the plant as Dortmund in the Ruhr valley, a large industrial complex noted for its history of coal mining and steel production. From the mid-1920s Renger-Patzsch embarked on a series of photographs documenting the changing face of the Ruhr landscape. Taking in a broad span of subjects – including mines, factories, railroads and workers’ housing – the series has become a historical inventory of the region. Once regarded as the antithesis of creative culture, Renger-Patzsch encouraged the re-evaluation of heavy industry as a topic that deserved attention. The formal properties of Renger-Patszch’s photographs bear comparison with the later photographic work of German artists Bernd and Hilla Becher (1931–2007 and born 1934) who in the late 1950s began systematically photographing ‘types’ of industrial structures (water towers, blast furnaces, gas tanks) in a similarly detached aesthetic style (see, for example, Coal Bunkers 1974, Tate T01923).

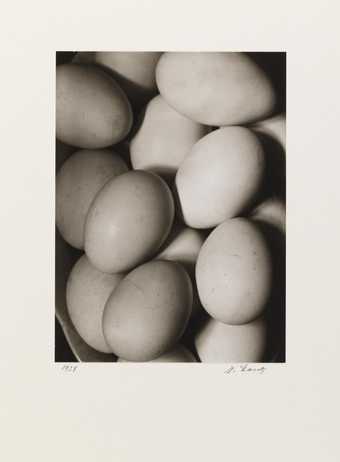

Renger-Patzsch’s images tie into contemporary debates about the role of photography in German society, bearing witness to a crisis over the proper function and potential of the medium. Noting how the clarity of photographic imagery corresponded to the ‘rationality and functionality’ of modern Germany, Renger-Patzsch aimed to ‘do justice to the stark web of lines of modern technology, to the massive girders of cranes and bridges, to the dynamism of 1,000 horsepower machines’ (Albert Renger-Patzsch, ‘Goals’, in Das Deutsche Lichtbild, Berlin 1927, p.xviii). In 1925 he published a text outlining his ‘Heretical Thoughts on Artistic Photography’, positioning himself in opposition to the popular Pictorialist style of art photography, characterised by atmospheric, soft-focus portraits and still lifes that were often manipulated or overlaid with coloured pigment. Renger-Patzsch criticised photographic attempts to ‘feign’ a painterly style, believing them to be ‘damaging to photographic achievement’ (Renger-Patzsch 1928, p.647). Instead, he insisted that photographers should master their equipment and employ rigorous camera work, so as to create realistic and descriptive images through purely photographic means.

Hörder Verein – Coal Mixing Plant (Dortmund) demonstrates this sober and precise style, characterised by sharp focus and purposeful framing. Alongside the German photographers August Sander (1876–1964) and Karl Blossfeldt (1865–1932), Renger-Patzsch came to be known as one of the leading proponents of this style of photography, labelled New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) following the 1928 publication of Renger-Patzsch’s picture book The World is Beautiful. (The term had originally been used by the art critic Gustav Hartlaub in 1925 to describe a new style of German painting.) According to the curator Matthew S. Witkovsky, Renger-Patzsch’s images ‘oscillate in subject between industry and nature: with a regular admixture of Gothic cathedrals, German churches and small towns’ (Witkovsky 2007, p.112). Gazing across the German landscape in all its variety, Renger-Patzsch captured simple insights into ordinary life with an almost encyclopaedic fervour.

Further reading

Albert Renger-Patzsch, ‘Joy Before the Object’ (1928), in Anton Kaes, Martin Jay and Edward Dimendberg (eds.), The Weimer Republic Sourcebook, Berkeley 1994, p.647.

Ann Wilde, Jürgen Wilde and Thomas Weski (eds.), Albert Renger-Patzsch: Photographer of Objectivity, London 1997.

Matthew S. Witkovsky, Foto: Modernity in Central Europe 1918–1945, exhibition catalogue, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 2007.

Sabina Jaskot-Gill

March 2012

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

This photograph shows the exterior of a mixing plant in which coal was sorted and cleaned, located in Dortmund in the Ruhr valley, Germany. From the mid-1920s Renger-Patzsch embarked on a series of photographs documenting the industrialisation of the Ruhr landscape. Like the majority of his industrial compositions, the scene in this image is deserted, devoid of workers, with the focus falling on the isolated building that dominates the composition. Shot from a low angle, the perspective lends the plant a monumental air.

Gallery label, January 2022

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- architecture(30,960)

-

- industrial(2,075)

-

- mixing plant(1)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- photographic(4,673)

- heating and lighting(846)

-

- coal(31)

- Germany(2,636)

You might like

-

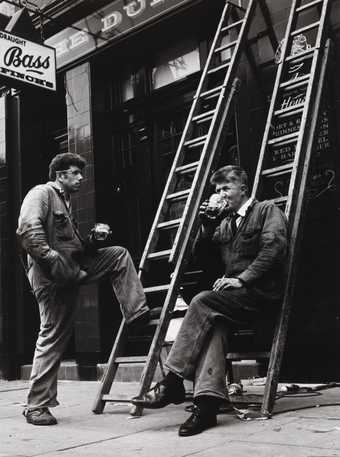

Dorothy Bohm Notting Hill, London

c.1960 -

Werner Mantz Title of WDR-radio programme, Cologne 1928

1928, printed 1977 -

Werner Mantz Interior, Cologne 1928

1928, printed 1977 -

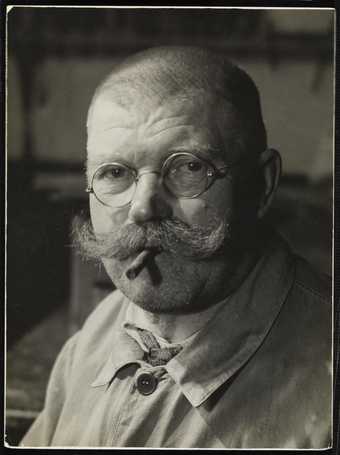

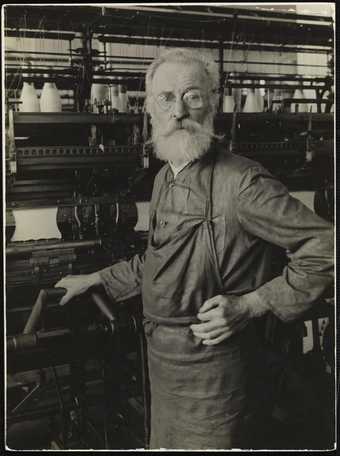

Albert Renger-Patzsch Woodcutter from the Ore Mountains

c.1933–4 -

Albert Renger-Patzsch Saxon Hosiery Weaver at a Handloom

1928–48 -

Albert Renger-Patzsch Bookbinder Gilding

date not known -

Albert Renger-Patzsch Picture Gallery Dresden

c.1928–9 -

Albert Renger-Patzsch From the Work: North German Brick Cathedrals, Stralsund - St Mary’s Church, Nave from the Choir

c.1928 -

Albert Renger-Patzsch Paderborn Westphalia Jesuit Church

c.1945–8 -

Albert Renger-Patzsch Greifswald, St Nicholas’s Church, Series: North German Brick Cathedrals

c.1928–9 -

Albert Renger-Patzsch Hamburg, Port

c.1929 -

Albert Renger-Patzsch Hamburg, Port Scene

c.1929 -

Albert Renger-Patzsch Münster in Westphalia, St Clement’s Church, Built by Schlaun

c.1929–39 -

Albert Renger-Patzsch Fortified Church in Grottrückerswalde, Ore Mountains

c.1935–7 -

Albert Renger-Patzsch Hamburg, St Nicholas’s Church

c.1929