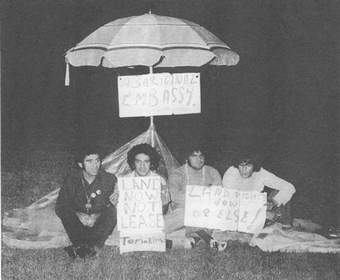

Fig.1

Richard Bell

Embassy 2013, installation view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2016

Canvas tent with annex, aluminium frame, rope, synthetic polymer paint on ply; 16 mm film transferred to single-channel digital video, black and white, sound; archive

Installed: 3050 x 6000 x 7930 mm; four sign boards: 600 x 1800 x 25 mm, 900 x 1240 x 30 mm, 900 x 900 x 50 mm, 1800 x 1200 x 25 mm; 1 hour, 11 min, 42 sec

Tate and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney

First created in 2013, Richard Bell’s artwork Embassy is a satellite of the Aboriginal Embassy, an ongoing political action started in Canberra in 1972 that asserts Aboriginal Australian sovereignty in the face of settler-colonial domination and the erasure of Aboriginal rights. Embassy consists of an ongoing and mutable installation made up of a tent and protest placards that play host to political discussions, lectures, film screenings and displays of other artists’ work (fig.1). It is in the process of being jointly acquired by Tate in the UK and the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia in Sydney, and has been the subject of research at Tate that examines how to collect and display an artwork that is ongoing, participatory and bound up in colonial histories and practices in which Tate itself is implicated.

In this essay I draw on my perspective as an anthropologist and as a research fellow at Tate to explore how some of the key discourses of the contemporary art museum may be looked at or reframed from the standpoint of Indigenous contemporary art. I begin by examining the wider context in which this acquisition of and research into Bell’s work has taken place, focusing in particular on the decolonial movement in museums and on inequalities in the UK cultural sector in recent years. I then look at how Embassy complicates the normative construction of public participation and refigures the forms of social connection that might take place in the museum, in order to ask how we might better understand the complicity of concepts such as participation or networks within broader colonial museologies. In doing so, I ask us to shift our perspective so as not simply to look at but to situate ourselves within, Bell’s artwork, and consider what might happen to our museological practices and our subjectivities as visitors as a result of this repositioning.

Reshaping the Collectible

This essay presents research and thinking undertaken during my four-month research fellowship for the project Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum at Tate in 2019–20.1 Through intense focus on specific artworks that are either in, or coming into, the Tate collection, Reshaping the Collectible asked how these works challenge and shape practices of collection care in the art museum. The project’s six case studies speak to, and aim to influence, key areas of museum practice. They include artworks like Bell’s Embassy that depend upon complex social networks for their activation and performance, and which produce living or ongoing archives; artworks that exist entirely on the internet; and artworks that require the museum to contain (even possibly collect?) political and activist practice.2 For each case study, the project team has explored, through a variety of different practitioner and academic perspectives, the implications of these material and social forms for museum policies and practices. They have generated ideas and proposals as to what museums need to do to enable these works to ‘live’ in the museum.3

As an anthropologist, I was invited to contribute a perspective drawn from the methodologies and debates within my discipline. I was also asked to bring in my experience working within collaborative museum projects that focus on participatory collecting, collections-based research, and the co-curation of exhibitions and digital projects, drawing on my long-term fieldwork in Vanuatu and New Zealand. In the background of my research and writing has also been the intense debate and scrutiny over the colonial legacies and representational politics embodied within museums as institutions – debates that have been simmering over many decades, but which boiled over in 2020, precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic and key international manifestations of institutional racism, especially the murder of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis in May 2020. Over the course of the fellowship at Tate I became interested in both the connections and disconnections between discourses and models of collaboration, decolonisation and participation within the contemporary art museum, and in understanding the boundaries that seem to separate collections of contemporary art from other kinds of museum collection.

This conversation was also inflected by the growing awareness and tensions within Tate that led to the development of significant initiatives from within the institution focused on decolonisation and institutional racism.4 As I wrote this article there were a number of loud calls, from a wide variety of different stakeholders across the museum sector, asking for public acknowledgment of the colonial foundations of museums; for restorative justice in the form of repatriation; for museums to address diversity in both their staff and stakeholders; and for divestment from industry funders whose products are widely recognised as damaging both nature and culture – from opiates in the case of the several high profile cultural institutions receiving funding from the Sackler family, to fossil fuel sponsorship at national museums such as the Science Museum and the British Museum.5 This ongoing demand for decolonisation asks for colonial histories and legacies to be recognised as underpinning the foundations of all museums. It asks for museums to be understood as implicated in broader processes of colonial violence – both past and present – through their ongoing practices of collecting, classification, archiving and display.

Writing through the outbreak of COVID-19 has also drawn into relief the ways in which health, healthcare, labour and economic survival are fundamentally informed by racial hierarchies that can trace their origins to European histories of slavery, of colonialism, and of resource extraction and exploitation. It has also become increasingly clear that the contemporary UK cultural sector is deeply implicated within these inequalities. This was highlighted by the publication of an interim report focusing on the colonial legacies of the National Trust properties and by the growing dismay about the precarious labour conditions of many museum workers at places like Tate.6 At the same time, cultural institutions are also vital social spaces and sites for civic engagement.7 The UK is now putatively entering a post-pandemic economic recession, marked by increasing polarisation around cultural politics.8 This has left those working within museums wondering how they can ensure that they do not continue to perpetuate the systemic inequalities that seem to be being reinforced rather than broken down by the rising cost of energy, tensions around immigration and education, and ongoing questions about the UK’s role in Europe and in the world.

The view from the tent

Given this backdrop of dissatisfaction, critique, precarity and uncertainty, here I unpack some of the key ideas that underpin the Reshaping the Collectible project through a focus on Bell’s Embassy. I situate myself as a first-generation British scholar who has had the privilege to work at the interstices between (and on occasion be a point of connection among) diverse communities and cultural collections. I have been lucky enough to participate within a growing movement in museums, as well as museum anthropology, that aims to prioritise the perspectives of stakeholders who are typically less visible, or even silenced, within museums in the Global North, and to recognise the rights of people to their cultural heritage that is often held far from their homes in museums around the world.9 In this essay, I have undertaken a thought experiment of a kind, exploring some of the Reshaping the Collectible project’s core terms as they might be seen from inside the tent.

As Aboriginal sovereign spaces, both the original Aboriginal Embassy initiated in 1972 and Bell’s 2013 Embassy ask those who enter them to re-situate themselves – to understand that the ground they are on is not an undifferentiated ‘public’ space, but rather re-zoned as an Indigenous space and place, governed by alternative rules and protocols, looking from there out and back at the nation-state and its citizens. In this essay I ask: what might some of the important questions for contemporary museums look like from inside the Embassy tent? What do participation, political activism and social networks look like from the perspective of an artwork that re-zones the terms of relation between spectator and spectacle, visitor and guest? I cannot and do not claim to speak for either Richard Bell or Embassy. Rather, I try to presence the alternative perspectives that Bell explicitly raises in his work and use them as a provocation to suggest how they might be internalised within museum theory and practice. In doing so, I am following an invocation by Bell himself, who wonders whether, rather than undertaking unwanted studies of Indigenous peoples, anthropologists might ‘analyse the colonialist cultures to understand the relationship between the imposition of powerlessness and terrorism’. However, in place of ‘powerlessness and terrorism’, I focus on questions around powerlessness and social relations within the museum.10

The Aboriginal (Tent) Embassy and Bell’s Embassy

WHITE INVADERS

YOU ARE LIVING ON

STOLEN LAND

REMEMBER THE LARRAKIA KULAKLUK DARWIN N.T

LAND RIGHTS CLAIMS

KULAKUK FOR LARRAKIA 700 ACRES

WE WUZ ROBBED

THIS LAND BELONGS TO WE LARRAKIA

LAND RIGHTS NOW

IF YOU CAN’T

LET ME LIVE

ABORIGINA

WHY! PREACH

DEMOCRACY11

Fig.2

Michael Anderson, Billie Craigie, Bert Williams and Tony Coorey protesting under a beach umbrella opposite the National Parliament House, Canberra on Australia Day, 26 January 1972

Tribune/SEARCH Foundation, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney

On 26 January 1972, William McMahon, then Prime Minister of Australia, announced that instead of recognising Aboriginal title in ancestral lands, Aboriginal people would be required to apply to the government for perpetual fifty-year leases for their land. Known as Australia Day, 26 January marks the annual, contested celebration of the day that colonial settlers first landed in Sydney and raised the British flag at Sydney Cove in 1788. McMahon’s announcement came on this day amid the heated context of a growing Aboriginal Rights movement that moved to reject the founding colonial doctrine of Australia as Terra Nullius (unoccupied land), and it therefore provoked anger and outrage.12 In response, four activists linked to the ‘Black Power’ movement based in Redfern, Sydney – Michael Anderson, Billy Craigie, Bert Williams and Tony Coorey – established a site of protest under a beach umbrella opposite the National Parliament House in Canberra (fig.2).13 They called the site the Aboriginal Embassy, drawing attention to the fact that Aboriginal people were considered non-citizens, even in and on their own land.

Fig.3

The Aboriginal Embassy, Canberra, January 1999

Over the next several decades, the Aboriginal Embassy expanded and contracted across a range of makeshift and temporary media. These included umbrellas, tents and signs, but most importantly an ongoing presence of protesting Aboriginal people (fig.3).14 The Embassy was dismantled and removed by police numerous times, yet it returned persistently, shifting over time not just in form but also in location, in Canberra and across Australia. In 1992 the Embassy was re-established on the lawn opposite what is now the former National Parliament House to commemorate twenty years of the action; at this point, it began to be referred to as the ‘Tent Embassy’ by the media.15 By 1995 the Australian Heritage Commission had added the Embassy to the National Register of Listed Properties. Celebrated by some as a uniquely Aboriginal form of placemaking, the very ephemerality of the Embassy in a sense guarantees its permanence.16 The Aboriginal Embassy is that place where Aboriginal nationhood and sovereignty is asserted, wherever that may be: at the front of a protest march, under a cardboard sign, or in the back of a police van.17

Fig.4

Richard Bell in conversation with Karrabing Film Collective as part of the installation of Embassy at Jerusalem Show VIII: Before and After Origins, Frontier Imaginaries, Al Ma’mal Foundation, Jerusalem, 2016

Photo: Issa Frej

Richard Bell, whose Aboriginal heritage is Kamilaroi, Kooma, Jiman and Gurang Gurang, was a part of the Aboriginal Rights movement from a young age. He worked in the Aboriginal Legal Service before becoming an artist. In 2013 he recreated a version of the Aboriginal Embassy as a travelling and performative artwork that has subsequently appeared in numerous galleries and biennales around the world.18 Conceived as a satellite to the Aboriginal Embassy, Bell’s Embassy takes the loose form of a tent that shelters an ongoing political conversation, hosting local activists and scholars in panels and discussion groups, and screening films (fig.4). The tent is also supported by replicas of graphic signs from the original Embassy action, bearing the slogans quoted above.

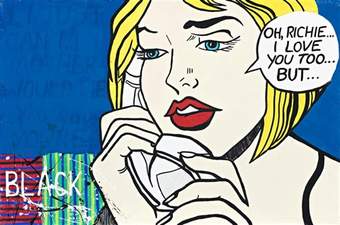

Fig.5

Richard Bell

Oh Richie… I Love You Too 2004

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas

600 x 900 mm

Courtesy Shapiro Auctioneers

© Richard Bell

Fig.6

Richard Bell

Scratch an Aussie 2008 (video still)

Video, high definition

Duration: 10 min

Courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane

Embassy forms part of a larger body of Bell’s work characterised by an irreverence for the institutional frames and canonical forms that embody colonial modernism. In a broad-ranging series of paintings and performances, Bell plays with key genres of Western art from abstract expressionism to pop, as can be seen in works like Oh Richie… I Love You Too 2004, a pop art pastiche that touches on racial politics (fig.5). With such works Bell critiques the canons forming around Aboriginal art, which he views as oppressive and hegemonic forms of appropriation that dovetail with racialised values around authenticity.19 Bell’s work is often controversial, playing with gender as well as racial stereotypes, in ways that often push on the boundaries of what is considered acceptable in the art museum.20 In Scratch an Aussie (fig.6), for example, Bell reverses the usual exoticism of Black bodies, placing himself as the ‘artist’ reclining with a group of scantily clothed blond Australian youths. Embassy, while a far more serious experiential and activist space, likewise draws attention to the shape and limitations of colonial icons and imaginaries.

Bringing Embassy to Tate

Bell’s Embassy is part of a growing body of contemporary art by Indigenous artists and activists that uses participation in the global art world as a platform to discuss dispossession and inequality. These works foreground alternative world views to those conventionally displayed in art museums, which have historically centred on European modernities.21 This reorientation has been a crucial part of Indigenous identity formation in settler-colonial states including Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the US, Brazil, Japan, and the Scandinavian states that encompass the Sami people. Settler-colonialism – the ongoing experience of Indigeneity under colonial rule – undoes the perception held in many European countries that colonialism took place within a finite period of time, now concluded, and chimes with the assertion of decolonisation theorists that coloniality is an ongoing experience and mindset rather than simply a historical period.22 Within settler-colonial nations today the ongoing effects of colonialism are inscribed upon the bodies of Indigenous people, who experience lower life expectancies and higher rates of infant mortality, poverty, incarceration and disease, such as cancer and diabetes.23

The United Kingdom, like many European countries, does not like to publicly talk of itself as a contemporary colonial nation (despite its continued claim over several overseas territories, from the Falkland Islands to Gibraltar). Contemporary pushes for decolonisation have been largely focused on thinking about the historical legacies of collecting, particularly in reference to slavery, which like colonialism is generally understood as a particular historical episode, now considered to be long past.24 Unlike in France and Germany, there is no state-sanctioned discourse or commitment to the repatriation of cultural collections as a mode of relating to histories of British colonialism.25 The particularity of British understandings of borders, seen through the lens of recent political events – the Brexit and Scottish independence referenda, immigration policies focused on former colonial subjects such as the Windrush generation, and the recent government desire to send asylum seekers to Rwanda – highlight a failure of the state to acknowledge and foreground the ongoing legacies of colonialism in British society.26

Within this context, museums are increasingly characterised as spaces for dialogue and reconciliation; places where colonial histories can be excavated and difficult relationships managed. However, the curators and anthropologists Johanna Zetterstrom-Sharp and Chris Wingfield, in their discussion of the role of the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in the recent decision of Jesus College, Cambridge to return a Benin cockerel to Nigeria, caution against the performative use of museums to redeem colonial histories. They argue that ‘the real assumption of “safe space” in the ethnographic museum’ is

a safety that emerges from saying the right things while being able to do very little … [I]n a context where action, instead of words, is demanded by contemporary political realities, modes of archival engagement with colonial pasts that have dominated in ethnographic museums are no longer a sufficient response.27

Bringing works such as Embassy to Tate – works that centre the experience of Aboriginal Australians as crucial to the presentation of not just global but British contemporary culture – should provoke museums to rethink their own complicity in an ongoing coloniality rather than viewing themselves simply as custodians of colonial histories. This should reshape the subjectivity of gallery visitors and reframe our perception of transnational or global history. This work is only just starting.

Participation

Embassy, the artwork, looks in two directions. It is situated as a work of contemporary installation art, and it is also a mimetic refraction of the Aboriginal ‘Tent’ Embassy – an ongoing assertion and performance of Aboriginal political sovereignty and its site of protest. The Aboriginal Embassy is described on Wikipedia as a ‘protest occupation’, although this is a loaded description which continues to deny the valence of the concept of an embassy.28 As a sovereign space, the Aboriginal Embassy reverses this gaze, arguing that from the Aboriginal perspective it is the Australian state that occupies Aboriginal land – initially without treaty, and more recently through the now illegal doctrine of Terra Nullius.29 As the Aboriginal Embassy mimetically appropriated the colonial notion of a national embassy, it also challenged the foundations of this system by constituting a claim that transcended both the legal foundations of the nation and its authorisation through the built environment. By creating an embassy, Aboriginal activists highlighted the paradox that they are both a native nation and foreigners in their own land. Bell’s artwork is a further mimetic appropriation: an embassy of the embassy. Like the Aboriginal Embassy in Canberra, Bell’s installation shifts across an array of temporary forms (umbrellas, tarpaulins, tents). It invites the participant-viewer into a space framed by Aboriginal sovereignty and offers a curated space of activity, from film screenings to panel discussions and lectures from Aboriginal and other activists. This complex refraction or process of mimesis powerfully absorbs colonial forms and structures while also rejecting or refusing them.30

Fig.7

Marchers in a land rights demonstration outside the National Parliament House, Canberra, 30 July 1972, in response to the forcible removal of the Aboriginal Embassy tents

Ken Middleton collection, National Library of Australia, Canberra

As both instantiations and critiques of citizenship, the Aboriginal Embassy and Bell’s Embassy complicate the normative construction of public participation, especially that constituted within civic spaces, from the Australian Parliament House to the National Museum of Australia. The moments of emergence of both embassies, in 1972 and 2013 respectively, are stamped by contemporary concerns regarding the boundaries of citizenship and the role of colonial processes of absorption and refusal. In Australia in 1972, debates were focused on Aboriginal peoples and their rights as citizens, but also as first peoples of Australia (fig.7).31 In 2013 Australia established Operation Sovereign Borders, deporting maritime asylum seekers to brutal offshore detention centres.32 In the UK, by 2013 Prime Minister Theresa May’s ‘hostile environment’ policy had turned its attention to British colonial subjects and began treating many of the Windrush generation as illegal immigrants.

Across this same timeframe, discourses of public participation in museums have flourished and participatory practice has become a benchmark for successful museum projects. Curator and educator Nina Simon’s influential work on the participatory museum exemplifies the shift in museum practice away from the authoritative and hierarchical broadcast of knowledge by experts and towards the sedimentation of authority through co-production and participatory design. Simon mobilises the language of user experience and co-design, generating a view of museum participation as a form of user-generated content in which visitors have become the users, and knowledge has become the content. As she observes: ‘Rather than delivering the same content to everyone, a participatory institution collects and shares diverse, personalized, and changing content co-produced with visitors.’33

In many institutional contexts, the discourse of participation may just as much instantiate a notion of the participant as a consumer or user of services as it would suggest a citizen-led transformative political and aesthetic project. Participation in this former mode is measured along the lines of consumer satisfaction rather than through the framework of civic engagement, with criteria for evaluation focused on individual satisfaction rather than broader, more social, registers of connection. Simon suggests that ‘traditional’ forms of organising participation (she uses the examples of community advisory boards and focus groups) are ‘limited by design’, and that the ‘democratic’ model of web 2.0 can open up participation to all visitors.34 This emphasis on democratic engagement through a crowd of individuals, rather than through historic forms of collective organisation, promotes an understanding of museum visitors as part of broader social worlds and configurations; indeed, it renders the culture, gender, race and class of these worlds not only invisible, but as impediments to participation, rather than the structures through which participation is always enabled. It also runs counter to the ways in which participatory practices have in fact tended to emerge within museums, in which relationships are built with groups of people, described using the lexicon of ‘source communities’, ‘communities of origin’ or ‘local community’.35

Art historian Claire Bishop has traced a global art history of participatory art or social practice that has its roots in leftist projects that aim to radically bring collective engagement into the space of the gallery and museum. She argues that participation increasingly speaks to constituencies who are already within the museum and art world, rather than reaching out to new stakeholders.36 Bishop criticises the emergence of participation as a specific aesthetic form, often detached from political process, which runs the risk of reproducing the conservatism inherent to museum worlds in which ‘idiosyncratic or controversial ideas are subdued and normalised in favour of a consensual behaviour upon whose irreproachable sensitivity we can all rationally agree’.37 Similarly, museum theorist Nuala Morse argues that participation in museums may often contribute to both a deficit model for social worlds outside of the museum (with the museum pitched as the saviour) and an extractive practice for institutions that ultimately serves to benefit the museum more than build relationships of care for communities.38

Both the more celebratory model of participation and the critiques that have emerged around it signal the importance of the form of institutional structures – rather than simply the relations that take place within them – in moulding how we engage with each other within museums. To enter the Aboriginal Embassy invites us to recognise the ways in which normative constructions of participation are racialised and linked to colonial histories, and asks us to challenge who in fact sets the terms of participation. Embassy the artwork invites this conversation to emerge explicitly in the form of curated discussions, lectures and presentations. Participants are drawn from local activist networks, and speak to localised concerns: for instance, Embassy played host to Black Lives Matter in the US and Sami Sovereignty in Moscow.39 Bell has activated Embassy as a deliberate counterpoint to a generic and flattened model of participation, inviting people at each exhibition site who are united in their commitment to exploring shared questions of social justice and political activism, with a particular focus on Indigenous and minority rights, and sovereignty over land.

Fig.8

Richard Bell

Embassy 2013, installation view as part of Bell Invites at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 2016

Courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane

One example is the manifestation of Embassy at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 2016, titled Bell Invites (fig.8). The artist invited Emory Douglas, former Minister of Culture of the Black Panthers, and extended invitations to numerous other groups including HipHopHuis (a Netherlands hip hop collective) and the University of Colour (a student group that emerged from the occupation of the University of Amsterdam in 2015 to advocate for a decolonising perspective at the university), who in turn were asked to invite artists and performers to participate. As Stedelijk curator Vivian Ziherl notes in her introduction to the exhibition, participation was positioned as a ‘methodology of alliance-building’ framed by political activist networks working to unravel the racial and colonial norms institutionalised through art world organisations and structures.40 Situating these conversations in the tent and within in the art museum invites the public not just to spectate but to become a part of these concerns and conversations. It asks them to explicitly situate themselves within these debates, moving against what artist and curator Lynn Wray describes as the ‘anti-authorial turn in art curating’ as a form of ‘curatorial activism’ that reverses the traditional constituents and sources of authority within the art museum. It does this by situating the artist as curator and the visitor as political activist, simply by virtue of their presence in the tent.41

Indigenous museology and other decolonising methodologies invite museum practitioners to start not with a relationship between an individual and an institution, or even between a collective of individuals, but with a recognition of how the normative definitions of identity, the state and the public are embedded within colonial culture. It asks them to consider how even the concept of participation may contribute to the perpetuation of these hierarchies and inequalities.42 Embassy reminds us that there are alternative cultural protocols that could, and might, structure relationships and forms of participation. These alternative protocols may explicitly reject the logic of participation inculcated by either the nineteenth-century notion of imperial citizenship or the twentieth-century model of the citizen as consumer. They might frame sovereignty as zoned; a fractured, often incomplete project, rather than an absolute state of being.43 They might privilege alternative rituals and practices of hospitality, welcome and discussion. What would happen if the ethos of Embassy was extended into the museum at large, becoming a state of normality rather than a state of exception? Can we consider what the global, the transnational, or even British art look like from within the tent, rather than simply thinking of the tent as part of the larger institutional context of Tate?

Social networks

Embassy invites and provokes us to understand our conceptual frames as situated and embedded in specific times and spaces. Similar to the term ‘participation’, the idea of the ‘social network’ has emerged as a collective manifestation that presents highly specific structurings of sociality – for instance Facebook, or the contemporary art museum – as neutral containers of culture, rather than as cultural forms in their own right. As in the case of participation, the idea of social networks normalises very particular modes of relating. The Reshaping the Collectible project has explored the social worlds that are both made by, and make, artworks, expanding our understanding of art away from bounded objects and towards networks of people and things.44

Networks are frequently characterised as neutral forms through which to track significant relations (understood as connections) between people, but also increasingly between people and objects. There has been an extensive academic discussion of the limits of network thinking within social theory, and of the epistemic challenges that museums pose to the network as a conceptual frame or container.45 In turn, museums are famous for the ways in which they disrupt the networked potential of objects by recontextualising, through processes of collection and exhibition, new narratives and practices of connection. In her influential 1991 essay ‘Objects of Ethnography’, performance and museum studies scholar Barbara Kirschenblatt-Gimblett describes the ‘surgical’ process by which objects are painstakingly rendered meaningful as representations of society or culture through processes of collection and display. She asks: ‘Shall we exhibit the cup with the saucer, the tea, the cream and sugar, the spoon, the napkin and placemat, the table and chair, the rug? Where do we make the cut?’46

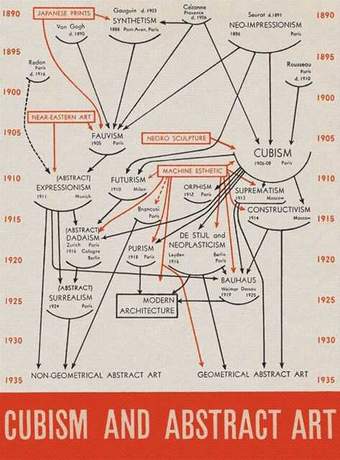

Fig.9

Alfred H. Barr

Diagram tracing the history of modernism on the cover of Cubism and Abstract Art, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1936

Similarly, writing of the ways in which social networks emerge as objects of analysis in anthropological theory, Marilyn Strathern argues that it is ‘cutting the network’, or recognising the points that punctuate endless moments of connection through rupture or discontinuity, that makes networks productive or viable.47 For Strathern, property relations and forms of ownership are mechanisms that limit connection: networks are curtailed or blocked by the assertion of ownership, or through other forms of claim-making. In my own work with the Vanuatu Cultural Centre and National Museum I have found that networks have been visualised according to customary protocols of exchange that shiver in tension with the borders of colonial administration: curators are caught between classifying objects in relation to makers, or owners, or in relation to local understandings of objects and identities as produced through connections to place. Even here, the understanding of place moves between a colonial rendition of place as a series of bounded localities, and a more Pacific understanding of island places as an entangled network of connectivity across land and sea.48

Fig.10

Detail from the interactive diagram of the history of modernism created for the exhibition Inventing Abstraction 1910–1925, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2012

Social networks can therefore be seen as epistemic objects in themselves that emerge, pre-cut, in order to contain the world within representational practices. As representational devices they teach us about which categories, entities and roles we consider to be meaningful participants within social fields. In the art museum today, social networks, much like participatory practice or community engagement, are also highly instrumentalised. Art historian Jonathan Patkowski and museum scholar Nicole Reiner have reflected on the canonical linkage of curator Alfred Barr’s 1936 diagram depicting the emergence of abstract art and the founding epistemology of New York’s Museum of Modern Art (fig.9), and the ways in which the diagram was updated and made interactive for the 2012 Museum of Modern Art exhibition Inventing Abstraction 1910–1925 (fig.10).49 They comment:

The [new] Artist Network Diagram provides a compass of influence that is calculated solely in terms of the number and quality of interpersonal relationships, or connections, a given artist had cultivated, and suggests that abstraction resulted from individual enterprise rather than from broader historical forces or cultural encounters. It also, and simultaneously, recasts cultural exchange and the figure of the artist according to the logics of neoliberalism, by picturing art history less as an evolution of avant-garde styles and more as the result of enterprising individuals, and by attaching cultural significance to social connection as much as stylistic innovation. This retelling suggests that the modernist artist achieved success not due to the amorphous forces impelling advanced art in modern times, but through his own agency, by establishing connections and capitalizing upon the insights, advice and exchange with peers. Call it the artist as cultural entrepreneur.50

This quotation highlights a sharing of form between consumer culture and the art world, in which participation in both is structured by a logic underpinned by a very specific kind of neoliberal subjectivity. Is an alternative network mapped within Embassy? What would be disrupted by and within the installation, which could be seen to ‘cut’ open the museum, bringing in connections and constituents that are not drawn together by the museum itself but by commitments to other institutions and ideas? In Embassy, the network is spatialised in the form of a tent rather than flattened into a diagram. Its co-ownership between Tate and the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia in Sydney links the UK and Australia through the shared colonial history of nation-building. The invited speakers, panels, films, artworks on display and the countless conversations that take place within the tent refigure the forms of social connection that might take place in the museum. As Embassy moves into these two museum collections simultaneously, how will the social world of the tent be collected or archived? In turn, who will curate and establish these connections in the museum if and when Bell is no longer available?

Fig.11

Richard Bell

Embassy 2013, installation view at Documenta 15, Kassel, 2022

Photo: Documenta 15

Collecting the intangible, or bringing non-museum practices such as political activism into the space of the museum, highlights the legacy of museums as ‘objectification machines’, to use sociologist Fernando Domínguez Rubio’s term.51 In this definition, museums work to substantiate, legitimate and preserve things as objects, very specifically in terms of material boundaries and limits, the conditions of ownership, and the translation into classification systems that support the interests and values of the institution. Some of these tensions have been explored in exhibitions such as Disobedient Objects at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (2014) and I Object at the British Museum, London (2018), both of which focused on objects created from within social movements to enable political activism. Yet as the curators of Disobedient Objects asked in their catalogue: ‘What happens when you place disobedient objects at the heart of a building that was conceived for such obedient purposes?’52 Do these exhibitions neutralise the radical capacity of social movements by converting them into objects of display? In the case of Embassy, might this work disrupt this process by importing a different set of networking practices that resist the objectifying tendencies of the art gallery (fig.11)? What is the risk of the art museum context rendering activist networks as performative – as objects to be viewed or consumed by the visitor – rather than transformative?

Towards decolonisation?

Fig.12

Decolonise This Place

Poster advertising ‘Decolonize This City: 2nd Annual Anti-Columbus Day Tour’ at the American Museum of Natural History, New York, 2017

Bell has described Embassy as ‘a public space [for] ideas, and thoughts, about globalism, capitalism, empire, colonization, patriarchy, whiteness, and issues affecting people’s daily lives’.53 In doing so, he situates the work within the growth of a global movement, largely aimed at the Global North, that calls for the decolonisation of museums.54 This movement sees activists, practitioners and scholars advocating for the broad acknowledgment of the entanglement of colonialism with collecting, conserving and representational practices in museums (fig.12).55 It advocates for the rethinking of texts and contexts in museum displays to allow for better representation of women, queer people and other minority groups, both within museum staff as well as in collections and exhibitions. As mentioned above, activists are also pushing for other kinds of social justice – from divestment from financial support from fossil fuels or pharmaceutical companies through to repatriation and other forms of reparative justice for colonial wrongdoing.56 Furthermore, decolonising movements advocate for historical awareness, and the acknowledgment of diverse privileges and other biases that have underpinned structures of authority and power in museums. For instance, the curators and museum theorists John Giblin, Imma Ramos and Nikki Grout have proposed a template for decolonising museums which includes the capacity to be able to sit with curatorial and audience discomfort; a renewed focus on the inclusion of silenced voices and histories; the decentring of European paradigms to expose and challenge colonially created subjectivities; and the requirement to present transparently the history of colonial collecting and display.57

It is not easy to acknowledge the legacies and inheritances of the past, and complicity in the present, and to work across profound differences of experience. In fact, my unravelling of the concepts of participation and social networks – both powerful structures for contemporary museology – has taken me towards the decolonial mindset of recognising how deeply the normative concepts that structure social engagement around collections are marked by colonial histories. This leads me to ask: how can Embassy work, not just as a marker of colonial experience, of settler-colonialism and Indigenous sovereignty, but as a device for decolonisation in the museum? This would require the tent to provide a blueprint for an institutional reorganisation and a shift in authority. What questions can be raised here about the ability of the museum to decolonise, and what potential is there for artworks to disrupt both conceptual and representational domination and colonially inflected institutional structures? Contemplated from within the tent itself, Embassy raises several provocative questions for an art museum in contemporary London.

There are a number of global shifts that occur when you extend the discussion of colonial inheritance to all artworks, not just those that have emerged explicitly out of colonial encounters or are made by those recognised as colonial subjects. To enter the tent identifies us all as co-opted within colonial projects and ongoing states of coloniality but also asks us to recognise the situated nature of this coloniality. This could be seen as the opposite of the concept of the transnational as it is defined by Tate – as a rubric for understanding ‘the global exchanges and flow of artists and ideas’.58 Tate’s is an approach in which the centring of Euro-American or old world perspectives is still implicit as the vantage point from which this global exchange and perspective can be constituted. Taking a decolonial mindset instead requires us to acknowledge the implications of being in this place at this time. The discourse of decolonisation should be seen as a disruption, or challenge, to the network, requiring us to rethink and make explicit our own position within it.

A call for new perspectives

I have been using Embassy to argue for a re-situation of our understanding of the institutional forms and constraints that structure our experiences within art museums. This re-situation asks us to shift our perspective so as not simply to look at but to situate ourselves within the artwork, and in doing so to consider not just our understanding of the work but how we can change the ways in which we enter, engage with and work with museums. Can this shift in perspective, looking out at the museum from inside Bell’s tent, allow us to alter the key terms and conditions through which we enter into the social contract of the museum? Can it likewise shift the subjectivity of both museum practitioners and visitors? Perhaps these ideas will be explored in the presentation of Embassy at Tate Modern in May and June 2023.59

Embassy is but one artwork that is chipping away at the comfort zone, as well as the contact zone, of the museum. It does this not just from the point of view of the visitor but also in the ways in which it challenges the work needed to create collections. The call for decolonisation asks us not simply to enhance our practices of inclusion, but demands that we imagine the museum itself as otherwise – to empower alternative structures of authority, and alternative practices of care and attention.