- Artist

- Donald Rodney 1961–1998

- Medium

- Acrylic paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 1200 × 1215 mm;

frame: 1270 × 1280 × 36 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the Donald Rodney Estate 2007

- Reference

- T12768

Summary

How the West was Won 1982 is a large square painting by the British artist Donald Rodney. In bright colours, rough brushstrokes and a child-like style, the work depicts an encounter between two figures in a desert landscape. On the left-hand side of the painting stands a pink-skinned man in black clothing and a large black hat. Grinning in a sinister fashion with his jagged teeth and pointed grey tongue prominent, he points what appears to be a gun at a figure wearing a feathered headdress associated with Native Americans, who faces the viewer with an unhappy expression. In the background light blue clouds and a vivid sun sit in a dark blue sky above the desert. The title of the work is written at the top of the painting in capital letters, while the artist’s name and the date 27 September 1982 run along the bottom edge. Curving around the body and the hat of the gunman is the phrase: ‘THE ONLY GOOD INJUN IS A DEAD INJUN’. The overall composition is framed with a black painted border containing intermittent white patches. The gun was represented originally by a red toy pistol glued to the canvas, but this was lost before the work was acquired by Tate in 2007 (see Beaven 2011, accessed 12 August 2014).

The title of the painting refers to the epic Hollywood film How the West was Won (1962), directed by John Ford, Henry Hathaway, George Marshall and Richard Thorpe. This source is perhaps alluded to by the painting’s black border with white patches, which resembles that of a film frame. Whereas the film depicted the colonisation of the American West as a brave and exciting struggle, Rodney’s painting suggests a less heroic and more crudely violent narrative. As the artist and art historian Eddie Chambers has argued, in How the West was Won Rodney critiques ‘Hollywood’s “cowboys and Indians” films that tended to present Indian resistance to settler domination as the criminality of savages, for which ruthless suppression was the only fitting response’ (Chambers 2003, p.40, note 17). ‘The only good Indian is a dead Indian’ is a phrase commonly attributed to the United States Army General Philip Sheridan, who is said to have uttered it in 1869.

How the West Was Won was made while Rodney was an undergraduate student at Trent Polytechnic in Nottingham, where he completed his degree in fine art between 1981 and 1985. It is closely related to another painting that he also dated September 1982, Sadly the Redskin Has His Reservations 1982, which depicts a desert meeting between a caricatured ‘cowboy’ and ‘Indian’. These two paintings were the first by Rodney to incorporate text, which became a consistent feature of his work. Both works demonstrate how the artist sought to examine the racial implications of historical events through dark humour, parody, and the appropriation of images from popular culture, especially film and comic strips.

Rodney’s work after How the West Was Won, which includes photographs, sculptures and installations, continued to explore aspects of racial identity, especially in relation to Britain’s colonial history, in combination with works investigating the condition of sickle-cell anaemia, from which the artist suffered (see, for example, In the House of My Father 1996–7, Tate P78529). In 1987 Rodney wrote, ‘Destruction, Oppression, State Violence, and Hidden History constitute the principal themes governing my work’ (quoted in Mappin Art Gallery 1987, p.27).

In 1981 Rodney joined a group of young black artists, including Eddie Chambers, Keith Piper, Marlene Smith and Claudette Johnson, who were known first as the Pan-Afrikan Connection, and then from 1984 as the Blk Art Group. They became an influential collective producing exhibitions, events and artworks that engaged with the politics of race. How the West Was Won was shown in one of the group’s earliest exhibitions, The First National Black Art Convention, Open Exhibition of Black Art, which was held at the Faculty of Art and Design Gallery at Wolverhampton Polytechnic in October 1982.

Further reading

Depicting History: For Today, exhibition catalogue, Mappin Art Gallery, Sheffield 1987, pp.26–7.

Eddie Chambers, ‘The Art of Donald Rodney’, in Richard Hylton (ed.), Donald Rodney: Doublethink, London 2003, pp.20–41.

Kirstie Beaven, ‘How Do You Deal with an Artwork that Has a Missing Piece?’, Tate Blog, 16 December 2011,

http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/blogs/how-do-you-deal-artwork-has-missing-piece, accessed 12 August 2014.

Richard Martin

August 2014

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Rodney made this work when he was still a student and it is one of his first political works. Referencing the 1962 Hollywood film of the same title, he has challenged the traditional American portrayal of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ in the colonisation of the American West. Whereas the film depicted the colonisation as a brave and exciting struggle, Rodney’s painting suggests a less heroic and more crudely violent narrative. The phrase painted around the figure on the left ‘The only good Indian is a dead Indian’ is a saying attributed to the United States Army General Philip Sheridan in 1869.

Gallery label, September 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- aggression(100)

- fear(262)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- headdress(136)

- actions: expressive(2,622)

-

- gesticulating(130)

- smiling(291)

- man(10,453)

- countries and continents(17,390)

-

- USA(622)

- social comment(6,584)

-

- colonialism(429)

- human rights(298)

- persecution(89)

You might like

-

John Walker Lesson I

1968 -

Peter Phillips Random Illusion No. 4

1968 -

Barrie Cook Painting

1970 -

John Walker Study

1965 -

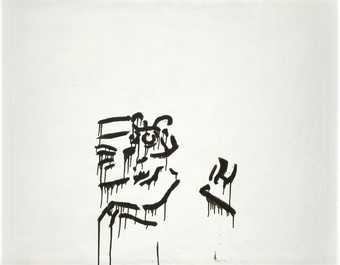

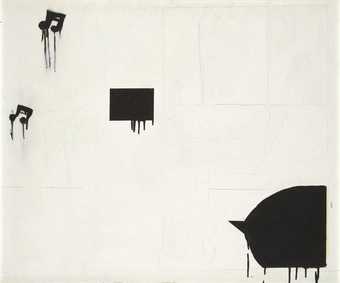

Donald Rodney Black Comedy 1

1997 -

Donald Rodney Black Comedy 2

1997