Not on display

- Artist

- John Singer Sargent 1856–1925

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 1630 × 1150 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the widow and family of Asher Wertheimer in accordance with his wishes 1922

- Reference

- N03709

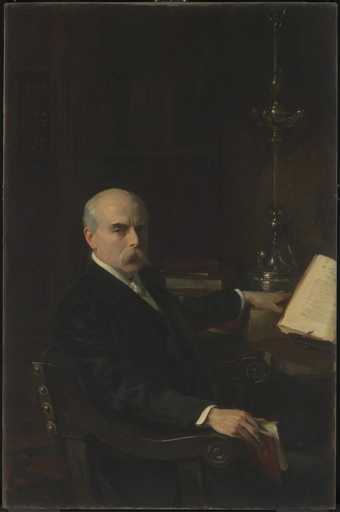

Technique and condition

The painting is signed and dated 1902. Alfred Wertheimer was the second son of Asher Wertheimer, Sargent’s Art Dealer and personal friend, and his portrait forms part of a series of Asher, Mrs Wertheimer and nine of their ten surviving children. Alfred was a chemist by trade, hence the two chemical flasks hanging in the left hand background as attributes. According to Robert Ross, the sitter died in the year this portrait was painted, at the age of 25, in South Africa. However, Mr John Matthias gives the year of Alfred’s death as 1901 (in a letter of 8 June 1961). It is thought that the artist could have signed and dated the painting later, in the year of its exhibition at the Academy. It was presented to the National Gallery by the widow of Asher Wertheimer in accordance with his wishes in 1922 and transferred to the Tate in 1926.

The painting is executed on fine linen canvas, which has remained unlined. There is a thinly applied pale grey oil ground, evenly distributed across the whole surface. It appears to be a commercial priming and is similar to that on the other paintings in the series. EDX has suggested that this ground is composed of lead white, chinaclay extender and bone black. Over the ground Sargent has applied a warm brown, thin, transparent priming which is most clearly visible at the lower right corner. This is a medium rich combination of lead white, iron oxide, chalk and chinaclay extender (see technical report, Joyce Townsend July 1998). Above this layer is an extremely loosely brushed, thin but opaque dark paint, applied in broad strokes, often circular or sweeping. The brushstrokes remain visible in the unfinished lower left corner. The warm brown priming remains visible beneath thin, opaque darker brown strokes in the lower right hand corner. The wooden table at the right lower corner is constructed largely from the effect of the warm brown underlayer remaining visible beneath a few broad, opaque darker brushstrokes. The books are created with broad single strokes of opaque, relatively bright colour (Naples yellow, bright green viridian, vermilion red all mixed with a quantity of lead white and ivory black) directly over the combination of the brown priming and the broad dark brushstrokes. The dark background is formed by these slashes of colour into the loose shape and form of the book covers.

The background appears generally unfinished in the lower half, but the top half has been divided into two distinct areas. In the top left half, the brushy strokes have been masked by opaque, pale grey/green paint to create a more solid backdrop for the chemical flasks which are created by a very few strokes of white paint, mixed with blue. At the top right, the background is much darker with a medium rich, more transparent black upper layer over a reddish underlayer, creating the effect of dark wallpaper.

Sargent seems to have painted the dark background first, using the brushstrokes to nudge inwards leaving a blank space where the figure will go. This technique is visible, for example in the hands (and is even more evident in the unfinished portrait of Edward Wertheimer). A gap seems to have been left in the dark background and the flesh of the right hand has been laid in loosely in this area. The contours of the hand then seem to have been redefined by going over the contours with dark opaque colour. This is also true for the left hand, which is very simply painted.

The grey suit of the body is painted loosely. There are areas in the right arm where the broad dark strokes of the background are left visible. There is no contour to the right of the sleeve, instead the pale grey used to create the creases just peter out into the background. The black shadows which are juxtaposed with these light creases are then painted over the pale grey and hollow out the valleys of the material. The collar of the jacket is created more or less by one stroke of rich black paint which outlines the shape and intimates shadow.

The richness of the dark paint and the fact that it is painted over an existing oil layer seems to be the prime cause of the extensive drying crackle in the black shadows. Sargent seems to have constantly readjusted the contours of the figure and the lighter elements of the painting, such as the newspaper (lower left corner) by painting around them with dark brushstrokes in the same colour as the background. This is also evident along the left hand side of the face, where a thick black stroke of paint gives the flesh colour a clean edge. The thickness of the paint in the face and the severity of the drying cracks suggest that the face may have been heavily adjusted by Sargent, painting with fairly medium rich oil colour over an already thick layer of paint. The gaps in the drying cracks reveal colours other than the grey ground beneath. In some areas it is flesh coloured, but in others it suggests that the features may have been shifted upwards in the final version. For example, in the cracks in the chin, bright red colours show through suggesting that the lips were further down originally and this red paint had dried quite considerably before the next layer was applied. The face itself is applied with fairly loose brushstrokes. The flesh colour appears to have been applied first with the brown/green of the shadows applied over it. The final light highlights have been applied last of all. This impression is reinforced in the cross-section taken from the area of the nostril. There are numerous layers, starting with the grey priming, then thick red flesh paint, covered with a bluish green layer. This lies beneath yellow flesh paint, covered with a dark red layer, then a mid red layer and finally the green-toned flesh paint. These numerous layers may also reinforce the idea that the face was repainted. The black hair is painted over the flesh layer.

It appears that the portrait was painted at least partially in the frame, as there is a border of approximately 25mm around the edges where the priming and only the initial layers of paint are visible. This impression is reinforced by the fact that the painting has subsequently been varnished within the frame, thus creating further discrepancies between the border and the body of the painting.

The painting does not seem to be as highly finished as other works in the Wertheimer series and the unfinished passages offer interesting insights into the technique. This painting also suffers from severe drying crackle which does not appear in any of the other paintings. This suggests that Sargent changed certain areas at a later stage and more extensively than any of the other paintings.

Annette King

July 1998

Catalogue entry

N03709 ALFRED, SON OF ASHER WERTHEIMER (?) 1901

Inscr. ‘John S. Sargent 1902’ t.r.

Canvas, 64 1/4×45 1/4 (163×115).

Presented to the National Gallery by the widow and family of Asher Wertheimer in accordance with his wishes 1922; transferred 1926.

Coll: As for N03705.

Exh: R.A., 1902 (157).

Lit: Robert Ross, ‘The Wertheimer Sargents’ in Art Journal, 1911, pp.4, 7, repr. p.7; Downes, 1925, pp.57, 198–9; Charteris, 1927, p.270, repr. facing p.168; Mount, 1955, pp.225, 234–5, 437; McKibbin, 1956, p.130; Mount, 1957, pp.187, 346.

Repr: Manson and Meynell, 1927, n.p.

Alfred (1876–1901), the second eldest Wertheimer son, was a chemist by profession, hence the two glass retorts which are shown hanging against the wall in the top left-hand corner of the picture. According to Robert Ross the sitter died in the year this portrait was painted, at the age of twenty-five in South Africa. However Mr John Mathias gives the year of Alfred Wertheimer's death as 1901 (letter of 8 June 1961), which would tally with the sitter's age. The artist could have signed and dated the painting later, in the year of its exhibition at the Academy.

Published in:

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, London 1964, II

Explore

- interiors(2,776)

-

- workspaces(918)

-

- laboratory(15)

- furnishings(3,081)

-

- table(754)

- book - non-specific(1,954)

- document - non-specific(119)

- test tube(4)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- standing(3,106)

- man(10,453)

- individuals: male(1,841)

- educational and scientific(1,494)

-

- scientist(81)

You might like

-

John Singer Sargent Professor Ingram Bywater

exhibited 1901 -

John Singer Sargent Mrs Wertheimer

1904 -

John Singer Sargent Hylda, Daughter of Asher and Mrs Wertheimer

1901 -

John Singer Sargent Ena and Betty, Daughters of Asher and Mrs Wertheimer

1901 -

John Singer Sargent Edward, Son of Asher Wertheimer

1902 -

John Singer Sargent Essie, Ruby and Ferdinand, Children of Asher Wertheimer

1902 -

John Singer Sargent Hylda, Almina and Conway, Children of Asher Wertheimer

1905 -

John Singer Sargent Claude Monet Painting by the Edge of a Wood

?1885 -

John Singer Sargent The Misses Hunter

1902 -

John Singer Sargent Mrs Charles Hunter

1898 -

John Singer Sargent Sir Philip Sassoon

1923 -

John Singer Sargent W. Graham Robertson

1894 -

John Singer Sargent Colonel Ian Hamilton, CB, DSO

1898 -

John Singer Sargent Portrait of Robert Mathias

c.1913 -

John Singer Sargent Mrs Carl Meyer and her Children

1896