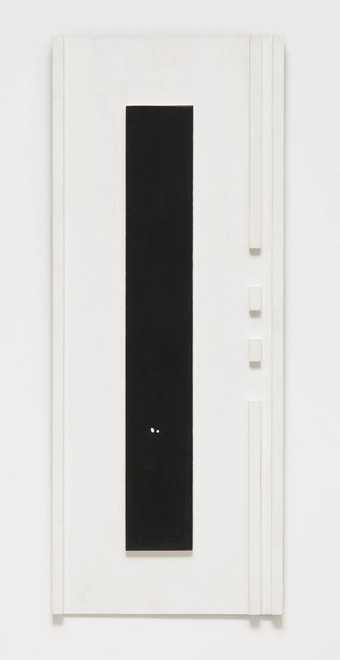

Not on display

- Artist

- Anwar Jalal Shemza 1928–1985

- Medium

- Wood and paint on hardboard

- Dimensions

- Object: 455 × 580 × 35 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by the Brian and Nancy Pattenden Bequest 2012

- Reference

- T13566

Summary

Composition with Number Six 1966 is made up of a series of wooden circles and semicircles that are affixed to a deep black, battened hardboard. The circles and semicircles are laid out in two configurations; one series of unpainted wooden pieces has a rectilinear format, while another set of pale blue painted wooden pieces is arranged into a more organic meandering line. The blue line forms the shape of the number six referred to in the title of the piece.

In this work Shemza investigates the possibilities held within the form of the number six, which when looked at upside down can also be read as the Arabic letter meem (or ‘m’). This work is representative of Shemza’s ongoing investigation into the possibilities of geometric shapes. Iftikhar Dadi, artist and academic, has noted that: ‘Many of Shemza’s works draw on a creative tension between geometric abstractions derived from the Roman alphabet, and the sinuous character of Arabic scripts’ (Dadi 2009, p.3). This interest in calligraphy combined with geometry is further extended in works such as Meem Two 1967 (Tate T13567).

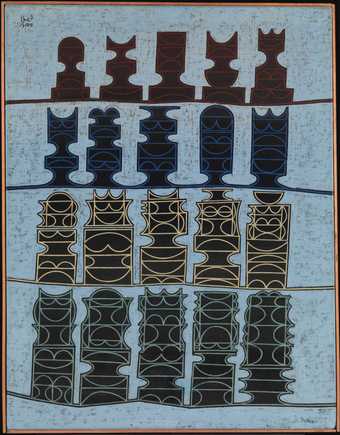

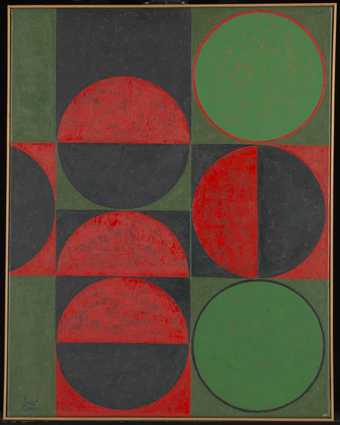

Much of Shemza’s practice is founded on the basics of geometry. This influence can be linked to his early exposure to traditional Indian carpet designs from his family business, but also more directly to Islamic design and Mughal architecture. Many of his works explore the relationship between basic geometrical shapes, such as the circle and the square. He stated: ‘A circle – a square – a puzzle – for which a lifetime is not enough.’ (Quoted in Dadi 2009, p.3.) The combination and the amalgamation of these two shapes provided infinitely flexible configurations that also brought him close to Arabic and Persian calligraphy. This interest can also be observed in both Chessmen One 1961 (Tate T13333) and Forms Emerging (Tate P79950), where the circle and square are deconstructed and reconfigured into a series of repeated and recognisable shapes.

Shemza always started his working process by making drawings in his sketchbooks. His works were meticulously planned out and he would make notes in Urdu and English about the development of particular pieces, tracing how he would realise and finish them. Peter Burnhill, who was on the staff at Stafford College of Art and Design where Shemza also taught from 1962 onwards, wrote of the artist’s practice:

Shemza’s sketchbooks show very clearly his primary interest – obsession, almost – with linear, rhythmically orchestrated and serially developed two-dimensional space, stored in the head and brought out in the very act of drawing rather than developed from observation. Page after page of his sketchbooks are covered with serial developments of black and white drawing from which he could select and later develop paintings in colour.

(Quoted in Shemza 1989, p.73.)

During his career Shemza explored a number of different subjects, such as the walls and gates of the city of Lahore in India, prayer carpets, electronic circuit boards, plant roots and the letter meem. He habitually worked in series and often produced numerous works before moving to another subject, although throughout his life he would return to earlier subjects.

Composition with Number Six reveals Shemza’s affinity for texture and his practice of applying different materials and media during the making of a work as a means of enriching and transcending the flat surface of a painting. Composition with Number Six is one of four works in which Shemza worked with wood. In later works, such as in the Root series, he made pyrographies with wood – designs made by applying burn marks to the wood’s surface – but in Composition with Number Six the wooden markers, made from sawn-off pieces of chair legs, sit on the picture surface. Shemza experimented with innovative techniques in other works, using his flip-flop sandals in the process of pattern-making by stepping into paint and then transferring his footprints to paper, or frequently working with hand-dyed cloth for printmaking. His focus on the relationship between the material used and the finished work signal Shemza’s modernist approach, in which the physical characteristic of the object, not just their visual effect, were crucial to the work. Composition with Number Six was first exhibited at the Commonwealth Institute Art Gallery, London in 1966 and the Commonwealth Institute of Edinburgh Festival in 1969.

Shemza was born in Simla, India in 1928 and studied at Lahore Mayo School of Art in Pakistan (1943–6) before moving to London in 1956 to study at the Slade School of Art. He taught for a short while when he was living in Lahore, which is what prompted him to come to London and experience European Art education with the hopes of teaching more effectively upon his planned return to Pakistan. However, his plans changed and he eventually settled in Stafford in 1962 where he took up a teaching job and remained until his death in 1985. Shemza’s years at the Slade were some of the most fundamental of his artistic development. His displacement allowed him to confront and question his previous practice, which was characterised predominantly by figurative and illustrative compositions. In London, his work developed towards an abstraction that fused Islamic motifs and calligraphic forms with western abstraction.

Further reading

Mary Shemza, ‘Anwar Jalal Shemza: Search for Cultural Identity’, Third Text, vol.3, nos.8 and 9, 1989, pp.65–87.

Iftihar Dadi, Perspectives 1 – Anwar Jalal Shemza: Calligraphic Modernism, London 2009.

Rachel Garfield, Perspectives 2 – Anwar Jalal Shemza: The British Landscape, London 2010.

Leyla Fakhr

January 2011

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- geometric(3,072)

- inscriptions(6,664)

-

- number(182)

You might like

-

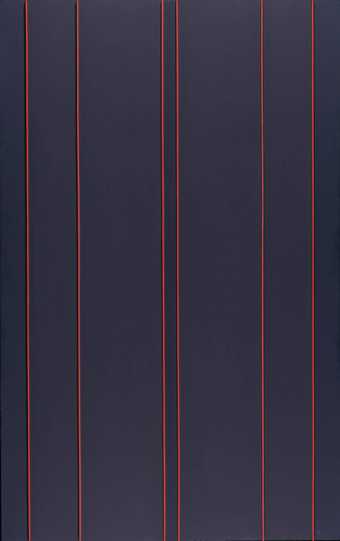

Peter Stroud Six Thin Reds

1960 -

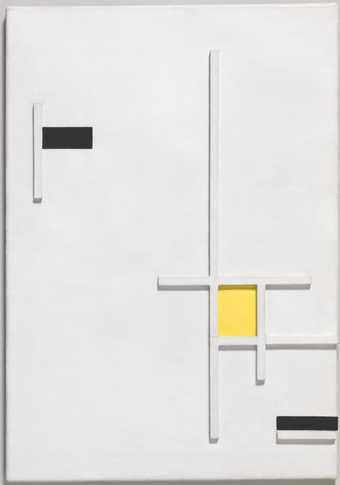

Marlow Moss Composition in Yellow, Black and White

1949 -

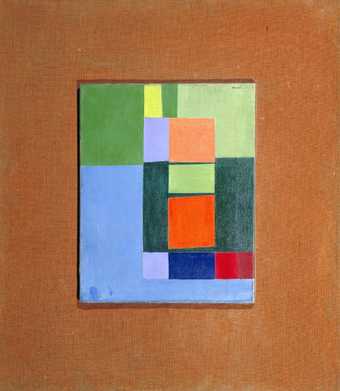

Kenneth Martin Composition

1949 -

Margaret Mellis Number Thirty Five

1983 -

Mary Martin Black Relief

1957–c.66 -

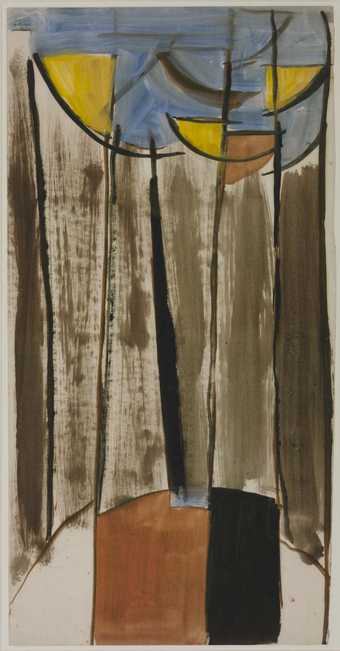

Sir Terry Frost Untitled Composition

c.1955 -

William Gear Composition

1949 -

Adrian Heath Composition, Blue, Black and Brown

1952 -

Li Yuan-chia 0 1=2

1965 -

Li Yuan-chia B N=0

1965 -

Anwar Jalal Shemza Chessmen One

1961 -

Anwar Jalal Shemza Meem Two

1967 -

Shafic Abboud Composition

c.1957–8 -

Saloua Raouda Choucair Composition with Two Ovals

1951 -

Anwar Jalal Shemza Composition in Red and Green, Squares and Circles

1963