Not on display

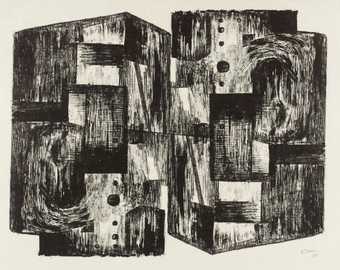

- Artist

- Anwar Jalal Shemza 1928–1985

- Medium

- Etching on paper

- Dimensions

- Image: 774 × 554 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 2010

- Reference

- P79950

Summary

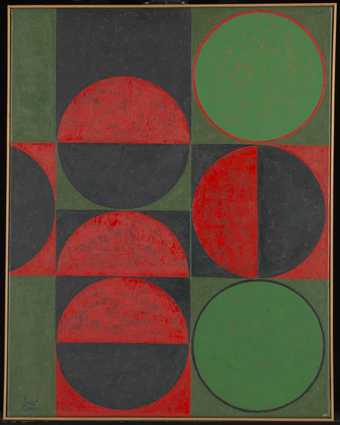

Forms Emerging is an etching in sixteen colours divided into four horizontal areas, each made from a separate etching plate. Throughout all four, the same abstract motif – a ‘waisted’ rectangle made by subtracting parallel semi-circular shapes from each long side of a rectangle – is repeated in different sizes and orientations. These motifs get progressively larger from the top to the bottom of the print. In each of the four horizontal bands, some of the forms are brighter and seem to emerge from the background, while others are less clearly defined and recede into it. The colour is rich and velvety, ranging from red to deep purple. Following early experiments with surface texture and pattern (see, for example, Chessmen One 1961, Tate T13333), Shemza distilled his experiences into a more disciplined formalist practice, much of it based on geometry. For example, on the work One to Nine and One to Seven 1962, he noted in Urdu: ‘A circle – a square – a puzzle – for which a lifetime is not enough’. These simple geometric forms would provide him with a set of limited, yet flexible, building blocks, through which to experiment with different arrangements of form, as can be seen in Forms Emerging. Tate’s copy is number one in an edition of five.

While studying at the Slade between 1956 and 1960, Shemza underwent something of a personal and artistic crisis. Having made a name for himself in Pakistan, he found himself moving from a position of power to one of powerlessness: ‘The “celebrated artist” was lost … as was also the beginner at the Slade. What’s more, I had lost my home. I was an exile, homeless, without a name.’ (Quoted in Hayward Gallery 1989, p.84.) This sense of displacement, and also the fact that his artistic production up to that time meant nothing to the London art scene, prompted him to destroy ‘paintings, drawings, everything that could be called art’. He wondered restlessly from place to place, until he found himself ‘in the Egyptian section of the British Museum. For the first time in England, I felt really at home.’ (Quoted in Shemza 1989, p.67.) His visits to the British Museum allowed him to study Islamic art from various regions and periods, something that he had not been able to do in Pakistan. He also studied the work of Swiss artist Paul Klee (1879–1940). From Klee he learned the importance of the flat surface as a plane for experimentation, and also the freedom to employ abstraction, geometry and pattern towards a modernist exploration.

Shemza was encouraged by his Slade tutor Andrew Forge (1923–2002) in his new experiments. Writing about Shemza’s work for his exhibition at the New Vision Centre in 1958, Forge said:

His paintings derive equally from the rhythmical space-filling patterns of the rug and from the ‘growing line’ of modern Western art. His pictures are not mere patterns but images, and their forms, whether painted or drawn, invest the surface with a mysterious life. They have much of the most characteristic quality of modern art; their content, their mood, the look that they address us with emanates directly from a musical play with simply related forms, from an asymmetrical order, from a sensitive response to the picture surface itself.

(Quoted in Shemza 1989, p.73.)

Further reading

Rasheed Araeen, The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-war Britain, exhibition catalogue, Hayward Gallery, London 1989.

Mary Shemza, ‘Anwar Jalal Shemza: Search for Cultural Identity’, Third Text, vol.3, issues 8 and 9, 1989, pp.65–87.

Anwar Shemza, exhibition catalogue, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham 1997.

Carmen Juliá

March 2010

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

You might like

-

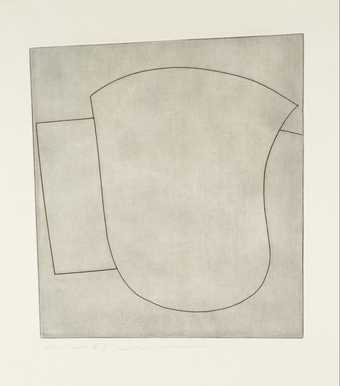

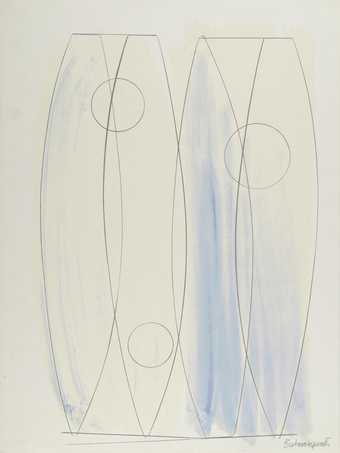

Dame Barbara Hepworth Sea Forms

1969 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Three Forms

1969 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Desert Forms

1971 -

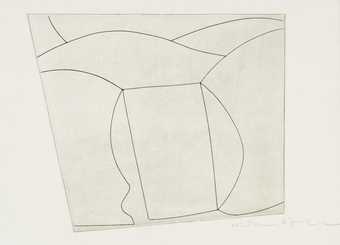

Ben Nicholson OM 2 sculptural forms

1967 -

Ben Nicholson OM 3 forms in a landscape

1967 -

Henry Moore OM, CH Square Forms

1963–8 -

Henry Moore OM, CH White Forms

1966–9 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth December Forms

1970 -

Paul Graham Graffiti on Motorway Sign, Belfast

1985, printed 1993–4 -

Paul Graham Republican Coloured Kerbstones, Crumlin Road, Belfast

1984, printed 1993–4 -

Paul Graham Union Jack Flag in Tree, County Tyrone

1985, printed 1993–4 -

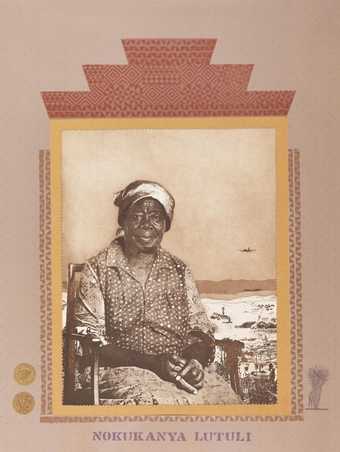

Sue Williamson Winnie Mandela

1983 -

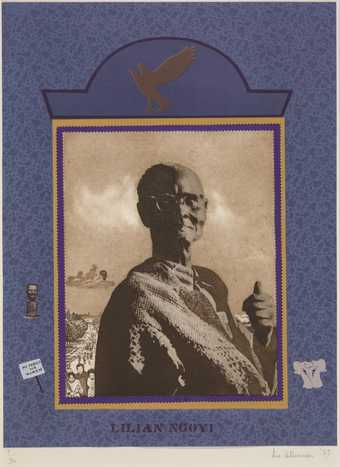

Sue Williamson Lillian Ngoyi

1983 -

Sue Williamson Nokukanya Lutuli

1983 -

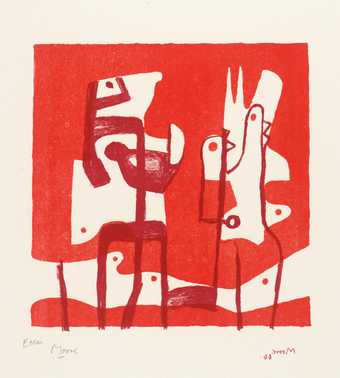

Anwar Jalal Shemza Composition in Red and Green, Squares and Circles

1963