In Tate Liverpool

- Artist

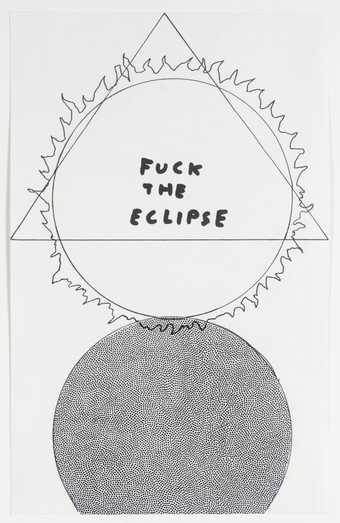

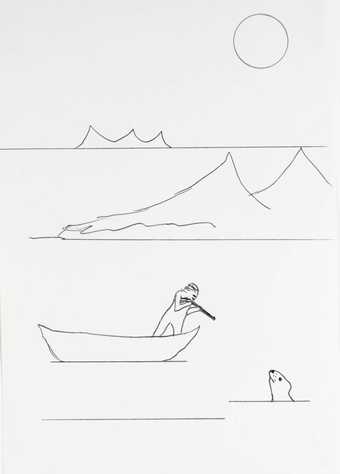

- David Shrigley OBE born 1968

- Medium

- Ink on paper

- Dimensions

- Support: 553 × 418 mm

image: 553 × 418 mm

frame: 638 × 498 × 22 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased using funds provided by the 2006 Outset / Frieze Art Fair Fund to benefit the Tate Collection 2007

- Reference

- T12358

Summary

This drawing shows two black silhouetted figures, joined so as to appear as one. As the words written on the page state, the image represents an elephant standing on a car. The car is a simplified representation of an old-fashioned vehicle such as a child might draw. Viewed from the side, it consists of an angled-off dark area between two parallel lines drawn using a ruler, sitting on two half-circles representing wheels. The elephant towers over the car, completely out of proportion to the vehicle’s size. Only the front part of its body is visible on the page, its front feet planted firmly on the car roof and the top of its head cut off by the edge of the paper. Its trunk is nearly as wide as its legs and it looks out at the viewer from a single large eye. This eye, like the centres of the car tyres, consists of a rounded white area with a black spot in the centre. The white area is bare paper, around which the artist has filled in the contours of the car and the elephant with black ink, applied with a brush. The words ‘elephant chooses to stand on your car’ are written in capital letters on five heavily-ruled lines next to the left of the elephant’s legs, under its trunk.

Shrigley’s drawing recalls the first chapter of the novel The Little Prince by French aviator Antoine de Saint Exupéry (published Paris, 1943) in which the child protagonist draws a picture of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant. Because the grown-ups he shows his drawing to think it is a drawing of a hat, he makes another drawing showing the inside of the snake, so that the adults can see it clearly, commenting ‘they always need to have things explained’. In Shrigley’s drawing, the identifying words appear at face value simply to explain an image that may otherwise be puzzling. The artist’s naïve drawing style and his unusual subject evoke a child’s imagination. Like the eyes painted on the tree trunk in Shrigley’s photograph, Fallen Tree, 1996 (P79241), the elephant’s outsize eye is humanising, turning a potentially alien and aggressive animal into a vulnerable character. The anthropomorphising effect of the elephant’s eye is reinforced by the use of the word ‘chooses’ in the caption, emphasising the animal’s free will. At the same time as being ridiculous – the chances of an elephant standing on anybody’s car in England or Scotland are so unlikely as to be laughable – the drawing has a sinister atmosphere resulting from the large areas of black ink and the outsized scale of the elephant in relation to the car. The drawing is unusually large for Shrigley, nearly the size of a poster. The artist’s identification of the car as ‘your car’ (addressing the viewer) suggests a mini narrative around the image. It becomes the product of a fictional character – the artist – who both is and is not David Shrigley – and who seems to be targeting the viewer as the unlucky victim of a force of nature. The words contain the relish of a malignant child thinking up an unpleasant fate to befall his or her enemy. For the extremely superstitious, drawing an event may actually make it happen. However, the suggestion is that if an elephant chooses to stand on your car, it is probably a punishment for something. And destroying your car is probably going to hurt you a lot.

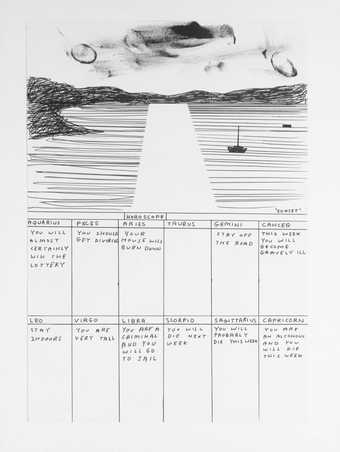

Shrigley’s exaggeration of moral codes in part stems from being brought up by Christian fundamentalist parents who influenced his formative years with a Biblical interpretation of the world. His work repeatedly satirises the kind of moral oversimplification inherent in the division of the world into good and bad, black and white. He mimics the formats of the many different kinds of text that bridge public and private spheres to reveal the humour in the common neuroses of everyday life. Shrigley has commented:

In a story there has to be something unusual, violent, something not mundane in any way. I think storytelling is good for my mental health, my state of mind, as all subjects that I touch upon come down to one kind of felt frustration or another, some latent anger ...

In a philosophical sense, my art is very fatalistic but hopefully the humour redeems it slightly from being just depressing. And when it comes to death – well, I prefer to see the humorous side of it as you can’t change anything about it anyway. Also, I think if you try to make some sort of fine gesture about the portrayal of God or the state of the world, you will inevitably fail. The only profundity you should ever achieve is in the particular, in very specific and personal things.

(Quoted in Muntendorf, pp.15 and 22.)

Further reading:

Caroline Muntendorf, ‘David Shrigley: Crooked Penmanship’, mono.kultur, no.9, December 2006/January 2007.

David Shrigley, Why We Got the Sack From the Museum, Bristol 1998.

Neil Mulholland, ‘Interview with David Shrigley’, http://www.davidshrigley.com/articles/nm_interview.html

, accessed 15 February 2008.

Reproduced http://www.davidshrigley.com/draw_htmpgs/stephen_friedman04/elephant.html

, accessed 7 February 2008.

Elizabeth Manchester

April 2008

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- cartoon / comic strip(177)

- silhouette(388)

- transport: land(2,189)

-

- car(502)

- inscriptions(6,664)

-

- caption(358)

You might like

-

David Shrigley OBE Fallen Tree

1996 -

David Shrigley OBE Carrots

1999 -

David Shrigley OBE Leisure Centre

1992 -

David Shrigley OBE Strive for Excellence

2013 -

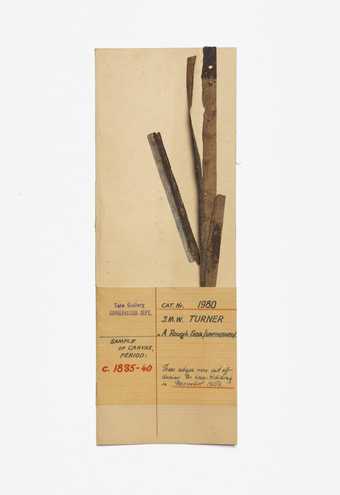

Cornelia Parker CBE RA From ‘Rough Sea with Wreckage’ circa 1830-5, JMW Turner, N01980, Tate Collection

1998 -

David Shrigley OBE Untitled

1999 -

David Shrigley OBE Untitled

2003 -

David Shrigley OBE Untitled

2003 -

David Shrigley OBE Untitled

1996 -

David Shrigley OBE Untitled

2003 -

David Shrigley OBE Untitled

1998 -

David Shrigley OBE Untitled

1999 -

David Shrigley OBE Untitled

1998 -

David Shrigley OBE Untitled

1998 -

David Shrigley OBE Stop It

2007