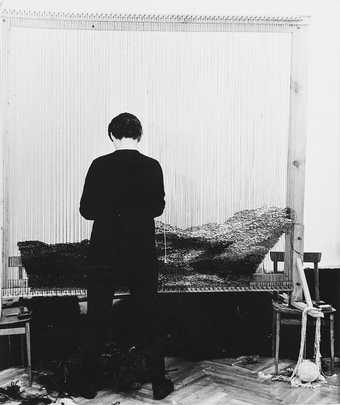

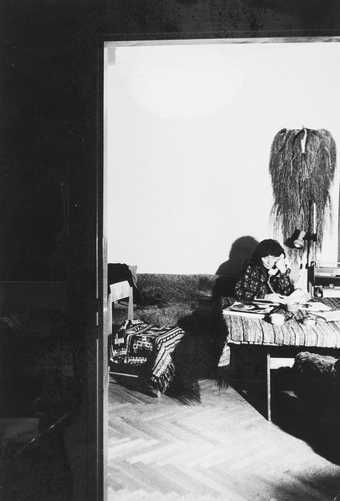

Magdalena Abakanowicz with Black Garment 1968 in her studio flat in Warsaw, Poland

Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego, Warsaw. Photo © Estate of Marek Holzman

The year is 1969. A female figure in black walks across expansive sand dunes. As she nears the camera, she enters an enigmatic environment of suspended, black woven forms. In 1975, the same strikingly beautiful woman, now wearing a dark-blue and purple crochet dress and carrying a single red rose, is greeting visitors at a public gallery in London. In another film, from 1982, she appears holding a crescent-shaped needle, stitching up the soft interior of a burlap sack. These three distinct decades, each marked by different political circumstances in Poland under Communism, make up the timeline for the exhibition of works by Polish artist Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930–2017) at Tate Modern.

Abakanowicz studied painting between 1950 and 1954 at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts. This important artistic institution was exposed to severe scrutiny by the Ministry of Culture and Art, especially during the period in which the authorities were promoting socialist realism. A loosening of the political grip after 1956, known as the ‘thaw’, led to the liberalisation of public life in the Polish People’s Republic, and this extended to culture, which was seen as an important part of the socialist project. Despite relatively modest economic conditions, the 1960s proved to be a fruitful period for artists. The strong presence of pedagogues who had been educated under the system preceding Communist rule, along with a lack of material resources, gave rise to improvisational tactics and a reliance on inventive approaches to making and thinking that challenged the many constraints imposed on everyday life.

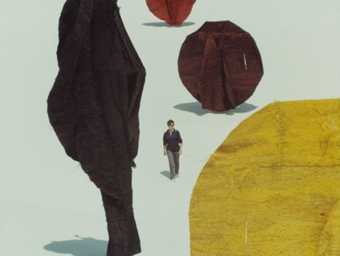

Still from Jarosław Brzozowski and Kazimierz Mucha’s film Abakany 1970

© Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego, Warsaw. Photo: Jarosław Brzozowski and Kazimierz Mucha / Wytwórnia Filmów Oświatowych sp. z o.o.

While still at the Academy, Abakanowicz, like several other students (mainly women), turned to weaving as an alternative to the prescriptive regime of painting. The influential figures of Mieczysław Szymański and Eleonora Plutyńska, who drew on a wide spectrum of textile tradition, introduced new possibilities for these students, reviving an interest in fibre as art, and elevating its status as a previously marginalised discipline to one of contemporary expression. Abakanowicz built on this, aiming to rid textile of its decorative or utilitarian associations. Her early explorations include titles that link her work with textile ancestry, for example Textural Composition White 1961–2 – also described by the artist as ‘Kilim (White)’ – Brown Coat 1968 or Black Garment 1968. These compositions still followed the convention of tapestry and were made on large looms and freestanding frames.

Magdalena Abakanowicz at her loom, 1966

© Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego, Warsaw

From 1967 onwards, however, a series of expressive, monumental fibre works signalled a radical departure. Often described as cloaks, carpet chambers or forests, they formed a cycle she called Abakans, highlighting an ontological connection to Abakanowicz herself. These singular forms, built from woven elements arranged into groups, later appeared as part of larger environments. ‘The Abakans began a cycle of contemplation spaces and sets of sculptures in open space,’ is how the artist described them in a film interview at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago in 1982, ‘They were my discovery, and making discoveries is extremely important, but they can’t be repeated.’

Magdalena Abakanowicz

Textural Composition White 1961–2

Sisal and cotton

164 × 106 cm

ASOM Collection. © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego, Warsaw. Photo © Abakanowicz Arts and Culture Charitable Foundation. Photo: Norbert Piwowarczyk

Artists working in Poland at the time were granted recognition and economic support in the form of stipends, awards and studios through the Artists’ Union. These monumental forms were made in one of those state-sponsored studios, where Abakanowicz lived and worked between 1965 and 1989. She described her first flat in a letter to art historian Michael Brenson from 1994: ‘I have spent most of my existence on the 10th floor of an apartment building together with my husband, in a tiny studio flat as the surface was limited to 9m2 per person ... We all lived in the same way amongst our neighbours – workers, writers, taxi drivers, musicians, doctors, all squashed in tiny cells.’ Creating works that she was able to fold and store was an ingenious way of not compromising her vision while working in limited space.

Magdalena Abakanowicz in her studio 1966–82

Photo Jan Kosmowski

Looking at the work today, viewers are more likely to find its relevance in the contemporary discourse around rebellious uses of craft – especially by women – and linking it to hybridity, ecosystems and the climate emergency. During the 1978 Fiberworks Symposium in Oakland, California, Abakanowicz declared: ‘I see fibre as the basic element constructing the organic world on our planet, as the greatest mystery of our environment. It is from fibre that all living organisms are built, the tissues of plants, leaves and ourselves. Our nerves, our genetic code, the canals of our veins, our muscles. We are fibrous structures. Our heart is surrounded by the coronary plexus, the plexus of most vital threads.’

Magdalena Abakanowicz in her studio 1966–82

Photo © Artur Starewicz/East News

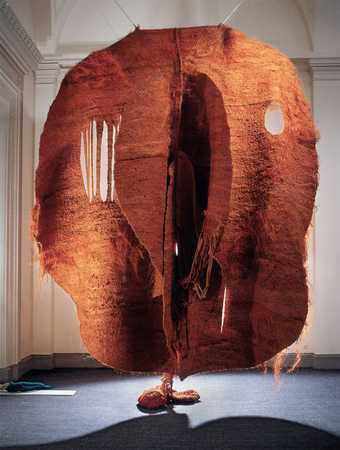

Exhibited, the works are charged with an erotic presence, teasing out uncertainty lodged between figuration and abstraction. Viewers are confronted with female-centred imagery, bringing up associations with sexual organs through the overtly open, slashed, red flesh of the fabric. There is a ‘tactile’ memory of roughness, temperature, emotion. Mentions of such references have been absent from reviews of her work: lacking in feminist interpretations, preference was given to evocation of the natural world.

Magdalena Abakanowicz in her studio 1966–82

© Artur Starewicz/East News

When addressing global art audiences, Abakanowicz frequently adopted a language of humanism. Her statements represented a call for attention to the spiritual dimension of art – in her mind, something that was much more enduring, capable of offering an alternative to expressing dissatisfaction with the political system. We can now more fully appreciate the relationships between Abakanowicz, the artist working in Eastern Europe under Communism, and the rest of the world. Her own commitment as a woman artist from behind the Iron Curtain was to break down barriers and expose lack of information. She put a substantial amount of effort into seeking and maintaining contacts with influential curators and critics across the globe. From her Warsaw studio, she ran a vast operation, aided by a couple of assistants, a telephone, a fax and a typewriter. While fighting the bureaucratic structures of the Artists’ Union, which administered all international exchanges, she made herself known through beautifully crafted, tender letters. In these writings we can hear her voice and learn about the patient construction of another kind of web, consisting of relationships with predominantly women professionals – curators, gallerists and museum directors. Among them were Alice Pauli, who exhibited her work at Galerie Alice Pauli in Lausanne in 1967, Mildred Constantine (MoMA, New York, 1969), Jasia Reichardt (Whitechapel Gallery, London, 1975), Erika Billeter (Kunsthaus Zürich, 1979), Mary Jane Jacob (MCA Chicago, 1982) and Suzanne Pagé (Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1982).

Magdalena Abakanowicz

Abakan Yellow 1970

Sisal and rope

380 × 380 × 70 cm

National Museum in Poznań. © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego, Warsaw. Photo © Abakanowicz Arts and Culture Charitable Foundation. Photo: Norbert Piwowarczyk

The artist was making her works at a time of intensifying political unrest that began in 1970 in Gdańsk and was only temporarily resolved by the short-lived Solidarity trade union movement, established in 1980. In retrospect, it is clear that the fabric of society, held together by Communist propaganda, was becoming exhausted and beginning to unravel. And Abakanowicz used art to reach beyond the regime’s oppressive agenda: in the same interview at MCA Chicago, she described how, after participating in the 1980 Venice Biennale, she was invited to show at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1982: ‘Two months after martial law was declared, the Minister of Culture gave me permission to travel. I was on a flight that was almost empty.’

Threads are everywhere – it is through these threads that the world conjured up by Abakanowicz in her many installations seems to be held together. The exhibition space doubles as an arena for an unspecified ritual by offering shelter and rescue from external pressures. The vulnerability of the woven constructions introduces an element of threat: pull or cut the wrong thread and the whole fabric could collapse, both metaphorically and literally. From the early 1970s onwards, Abakanowicz treated every solo exhibition as a unique work in progress. In the many films documenting this process, viewers see the artist thinking on her feet, rearranging the woven forms, lifting and suspending the heavy structures, detangling and caressing the fibres, and carrying out the final adjustments with needle and thread in hand.

Orange Garment 1968 at Stockholm Nationalmuseum, 1970

© Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego, Warsaw. Photo: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

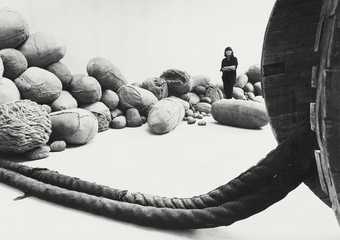

In 1980, while researching my dissertation at the University of Warsaw, I interviewed Abakanowicz in her studio. She was working on the Embryology 1978– 81 series, which was shown at the Polish Pavilion of the Venice Biennale that year. What struck me during that visit was the precision with which Abakanowicz articulated her thinking in relation to making, and how this profoundly philosophical discourse contrasted with the tangle of woven, sewn, tied and loose fibres spilling out of bags; the structures stretched, progressing onto frames in a scene that felt like a set of spatial notations, ideas materialising at different speeds. I recall the calm, decisive voice of the artist muted by the softness of organic elements, where everything seemed to be happening at once. The tiny but elegant studio with wooden parquet floors was incongruous with the scale of the production taking place.

Magdalena Abakanowicz with Embryology 1978–81 and Wheel and Rope 1973 in the Polish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, 1980

Tate. © Fundacja Marty Magdaleny Abakanowicz Kosmowskiej i Jana Kosmowskiego, Warsaw. Photo © Artur Starewicz/East News

The exceptional coherence and sense of commitment expressed by the woven forms continue to make an impact beyond their original invention. Together with the humble, sprawling Embryology, built around repetition and accumulation – traits present in Polish conceptual art – these works exceed the claims and counterclaims made around them during the time they were produced. It seems that, in our technologically dominated existence, contemporary audiences appreciate less processed approaches, seeking out visceral presence expressed as slow time, care of ecological systems, and the inventive repurposing of existing materials. These works, therefore, might be welcomed as acts of positive transgression.

Magdalena Abakanowicz: Every Tangle of Thread and Rope, Tate Modern, until 21 May. Curated by Ann Coxon, Curator, International Art, Tate Modern, Mary Jane Jacob, Independent Curator and Dina Akhmadeeva, Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern. Supported by the Abakanowicz Arts and Culture Charitable Foundation with additional support from the Magdalena Abakanowicz Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Members. Organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with the Fondation Toms Pauli at the Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne/Plateforme 10 and Henie Onstad Art Centre, Høvikodden.

Marysia Lewandowska is a Polish-born British artist based in London.