Not on display

- Artist

- Mark Wallinger born 1959

- Medium

- Video, projection, colour and sound (stereo)

- Dimensions

- Duration: 7 min., 20 sec.

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the Patrons of New Art (Special Purchase Fund) through the Tate Gallery Foundation 1997

- Reference

- T07394

Summary

Presented by the Patrons of New Art (Special Purchase Fund) through the Tate Gallery Foundation 1997

T07394

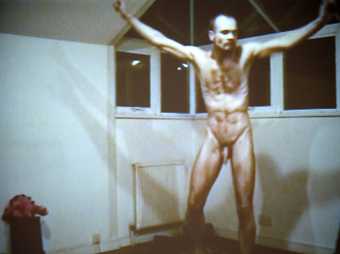

Angel is a seven and a half minute video. It was produced in an edition of ten, with two artist's proofs. Tate's copy is number six in the edition. The video is played continuously on a loop and can be displayed on a monitor or projected so that the image fills the gallery wall. Angel should be seen in a room on its own, but it also forms the first part of Talking in Tongues Wallinger's trilogy that includes Hymn 1997 (Tate T07798) and Prometheus 1999 (Tate T07742). Each video explores the theme of religion and features Wallinger playing Blind Faith, his sightless alter ego. He is seen in a different situation in each one, singing or reciting a text drawn from classical or popular literature.

In Angel Wallinger wears dark glasses and taps the ground with a blind person's white stick. He is seen walking on the spot at the foot of a moving escalator in the Angel underground station, London. In this awkward position he delivers a monologue, repeatedly reciting the first five verses of St. John's Gospel from the King James version (1611) of the Bible:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by him; and without him was not anything made that was made. In him was life and the life was the light of men. And the light shineth in the darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not.'

The words are oddly indistinct and Wallinger's voice has a garbled quality that could be said to evoke the speech of the deaf. This is because the artist recorded himself saying the words backwards while attempting to maintain the original speech patterns and emphases of the correctly spoken piece. The tape was then inverted during editing so the words would make sense when played. As a result, the rest of the film is seen in reverse, the end of the film being the beginning and the people on the escalators appearing to walk up and down backwards. Angel finishes as Wallinger stops walking and talking and, in a mock ascension, he rises slowly up the escalator, carried away to the triumphal sounds of Zadok the Priest (1727), Handel's (1685-1759) anthem for George II's coronation (1727) in Westminster Abbey.

Angel was shot in one long continuous take and was not cut during editing. The work's name comes from the Angel underground station where it was filmed. In his earlier work Wallinger was frequently the protagonist. For instance, in Self Portrait as Emily Davison 1993 (Anthony Reynolds Gallery) Wallinger photographed himself in drag, impersonating a female jockey. In Angel he plays his alter ego, Blind Faith. In both works Wallinger is performing, playing a character other than himself. In an interview with the curator Theodora Vischer he described himself as a 'cipher an actor, a puppet, a hollow man' who 'pretends different roles' and never speaks 'anything that has not already been written.' (Quoted in Vischer, p.26.) Yet despite the performative approach, Angel and the other videos in the Talking in Tongues trilogy differ from Wallinger's works of the early 1990s. In the Emily Davison photograph Wallinger explored issues of gender, national identity and sport, whereas Angel reflects his growing preoccupation with religious belief. This interest is most obvious in his choice of texts for the Talking in Tongues trilogy. He has noted that they relate to religious themes and 'suggest the possibility of transformation or redemption.' (Quoted in Vischer, p.26.) Wallinger also sees the works as evoking the longing of 'anyone who ever desired faith, innocence and eternal life.' (Quoted in Vischer, p.26.)

In Angel Wallinger presents the spectator with a series of paradoxes: time and speech appear to run forwards while in fact playing backwards, going up is going down and moving is staying still. As a result viewers are unable to believe their eyes and the supposed truth of the documentary medium appears to be undermined. Appearances are inverted and Wallinger's contradictions reflect those which he perceives as inherent in Christianity, where God is man or bread is seen as flesh. The work's visual ambiguity is also echoed by the paradoxical nature of St. John's Gospel recited by Wallinger and the spectator is asked to consider religious belief in a realm beyond the visible. Angel thus relates to much of the work Wallinger was producing at the time. In Seeing is Believing 1997 (Anthony Reynolds Gallery) he created a false optician's eye test. Between a red and a green light box, Wallinger printed not the normal selection of random letters but the first sentence of St. John's Gospel in letters of decreasing size. The work contrasts religious belief with the quest for empirical certitude symbolised by the optician's eye chart. It suggests that, as in Angel, seeing is not necessarily to be equated with believing.

Further Reading:

Theodora Vischer, Mark Wallinger: Lost Horizon, Museum für Gegenwartskunst Basel, Basel 2000, reproduced (colour) p.27

Mark Wallinger: Credo, exhibition catalogue, Tate Liverpool, Liverpool 2000, reproduced (colour) p.48

Tom Lubbock, 'Wallinger and Religion', Modern Painters, Vol.14 No.3, Autumn 2001, pp.74-7, reproduced p.75

Imogen Cornwall-Jones

February 2002

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- architecture(30,960)

- universal concepts(6,387)

-

- ambiguity(310)

- actions: processes and functions(2,161)

-

- looking / watching(581)

- group(4,227)

- self-portraits(888)

- religions(181)

-

- Christianity(2,755)

- dress: fantasy/fancy(506)

- arts and entertainment(7,210)

-

- artist, multi-media(393)

You might like

-

Mark Wallinger Half-Brother (Exit to Nowhere - Machiavellian)

1994–5 -

Mat Collishaw Hollow Oak

1995 -

Gillian Wearing CBE Confess All On Video. Don’t Worry You Will Be in Disguise. Intrigued? Call Gillian Version II

1994 -

Sam Taylor-Johnson OBE Brontosaurus

1995 -

Tracey Emin Tracey Emin C.V. Cunt Vernacular

1997 -

Mark Wallinger Prometheus

1999 -

Mark Wallinger Hymn

1997 -

Mark Wallinger Sleeper

2004 -

Catherine Sullivan The Chittendens: The Resuscitation of Uplifting

2005 -

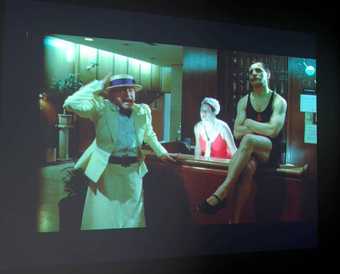

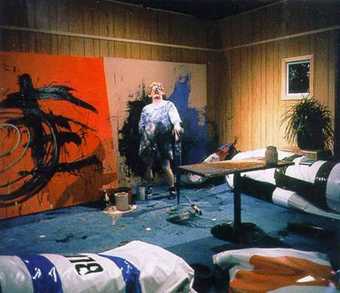

Paul McCarthy Painter

1995 -

Simon Martin Carlton

2006 -

Mark Wallinger Royal Ascot

1994 -

Mark Wallinger Threshold to the Kingdom

2000 -

John Smith Hotel Diaries

2001–7 -

Mark Wallinger Construction Site

2011