Not on display

- Artist

- Alfred Wallis 1855–1942

- Medium

- Staple bound paper covered sketchbook; 16 works on paper, coloured pencil, graphite and chalk

- Dimensions

- Object: 215 × 280 × 3 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased jointly by Tate and Kettle’s Yard with funds provided by the National Heritage Memorial Fund, Tate Members, Friends of Kettle’s Yard and with Art Fund Support 2021

- Reference

- T15765

Summary

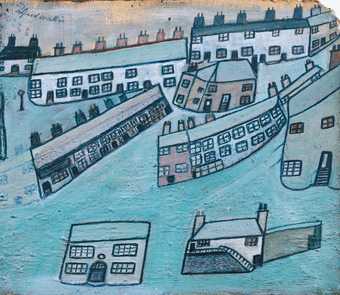

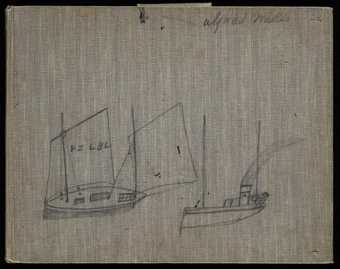

Castle Book is a children’s drawing book in landscape format with a creamy buff paper containing drawings in colour and graphite pencil by Alfred Wallis. It contains sixteen drawings, all of which are double-sided except for those using a bright red crayon on the inside front and back covers – the crayons used for the drawings are blue, red, purple, black, green and brown. The subjects are, in the main, fishing and sailing boats as well as steamers in differing landscapes, singly and in groups. One drawing seems slightly anomalous amongst the images of fishing boats, being a graphite pencil drawing of an ocean liner. The identification of the sketchbook as Castle Book refers to the printed image of a looming image of a castle that appears on its front cover, and was first designated by Sven Berlin in his 1949 monograph on Wallis. Leaf 1 verso, leaf 2 recto, leaf 4 recto and verso, leaf 5 recto and verso, leaf 6 recto and verso, leaf 7 recto and verso are all upside down. The leaf between 2 and 3 has been torn out leaving a stub. Seven drawings are not signed, nor are the drawings on the inside front and back covers; one is signed in capital letters ‘ALFRED WALLIS’, one is signed in cursive script ‘a. Wallis’ and the remainder are signed in cursive script ‘alfred Wallis’.

Castle Book is one of three books known to have been used by Alfred Wallis in the last year of his life after he was moved from his home in St Ives, Cornwall to the Madron Institute, the local workhouse, where he was looked after until his death in 1942. The other two books are known as Grey Book and Lion Book (Tate T15763–4); all three were formerly in the possession of Wallis’s friend and fellow artist Adrian Stokes (1854–1935) who gave them to his son, Telfer Stokes, when he was a young child. In the workhouse, Wallis was not only away from his home but was also removed from the source of his customary materials – off-cuts of bits of cardboard and wood as well as household items from table-tops to jugs – and the everyday marine paints that he used. Following the intercession of fellow artists and friends Ben Nicholson and Adrian Stokes, Wallis was allowed to paint and became reliant on artists’ materials that both Nicholson and Stokes supplied him with – pencils and crayons, sketchbooks and enamel paints. In the month before Wallis died, Nicholson was asked by him to supply tins of enamel paint, as he recounted the following year: ‘“I want black and white and green. Enamel. In tins. 6d. each.” As he had recently been using blue I said: “What about blue?” “No,” he replied, “I want Black and White and Green.”’ (Ben Nicholson, ‘Alfred Wallis’, Horizon, vol.VII, no.37, January 1943, p.53.) The colours mentioned by Nicholson are to be found in the Grey Book and may indeed be found to be enamel paint rather than oil paint.

The artist Sven Berlin wrote the first monograph on Wallis during the Second World War and it was ultimately published in 1949. In it he described these three sketchbooks (and one additional book, the current whereabouts of which is unknown) that Adrian Stokes had lent him:

A good deal of painting was done at Madron and some excellent drawings. The drawings were done mainly in greasy crayon – some in pencil. Nicholson had taken him four sketchbooks, which he filled on both sides of each page in a very short time. These are extremely interesting. Although the soft paper and the smooth crayon proved too woolly a medium for him, he managed to produce some startling results. For the sake of classification, I gave each of these books a name when they were loaned to me by Adrian Stokes: the Castle Book, the Grey Book, the Lion Book and the Scrap Book.

It is interesting to notice the various styles: the classic austere line of drawing of a Liner from the Castle Book might be from the hand of some early Greek draughtsman. It is sensitive, simple and frail. The conceptual image reminds one of Picasso. The drawings of Fishing Boats: PZ, L8L, taken from the cover of the Grey Book, were, I thought, by Nicholson when I first saw them. The Lion Book is more tumultuous, presenting a curious turn towards the baroque: one notices the same thing happening in the later drawings of Van Gogh … One is at a loss to know how Wallis expressed so much dynamic strength with so strict an economy of means.

(Berlin 1949, p.114.)

One aspect of the books that Berlin did not address, however, is what the sequence of drawings within the sketchbooks might communicate. The preservation of the sketchbooks is of interest in this respect because only in a few instances can Wallis’s paintings be dated, and so the relationship of painting to painting is otherwise lost. One key example of this is the sequence of the last three drawings in Grey Book that appears to communicate Wallis’s interpretation of the Noah’s Ark story: the first drawing [leaf 8, verso] shows a houseboat sited on a green plateau, perhaps corresponding to the Ark on Mount Ararat following the subsiding of the flood; the next drawing [leaf 9, recto] shows a valley or cliffside and headland view of a congregation of people on top of a hill and around its base with three tabernacle structures – perhaps an indication of survivors giving thanks following the flood’s aftermath; the last drawing [leaf 9, verso] shows an estuary landscape of fields emphasising a rebirth or renewed creation following the flood. Wallis was a devout and religious man – on Sundays he would cover over any of his paintings in his home and spend the day reading his family Bible. It would be surprising if his faith didn’t come through in his paintings. Edwin Mullins, in his study of the artist, made reference to one account where Wallis refers to his representation of over-size fish (for example as in Grey Book leaf 3 recto and leaf 8 recto), saying, ‘That fish stands for all the fish that have ever swum – for all the fish that God ever put in the sea.’ Mullins even made the suggestion that ‘the animals … were associated in his mind with the animals set free from the Ark. The notion of a world purged of sin by flood and repopulated with innocent creatures from the Ark is precisely the kind of ideal that a man with Wallis’s puritanical views would be expected to hold.’ (Edwin Mullins, Alfred Wallis, Cornish Primitive Painter, London 1967, pp.88 and 92.)

The sketchbooks underline the extent to which the heart of Wallis’s work is contained within his assertions that, ‘What I do mosley is what used to Bee out if my own memery what we may never see again as Thing are altered all To gether Ther is nothin what it was sence i can Rember.’ (Letter to H.S. Ede, 6 April 1935.) ‘The most you get us what use to Be all i do is Hout of my mery i do not go out any where To Draw.’ (Letter to H.S. Ede, 1 April 1936; both letters transcribed in Irish Museum of Modern Art 1999, p.65.) The mix of different styles and age of boat, the relationship of boats to land and to isolated landmarks, the repetition and variation of particular subjects and views all speak to the retrieval of memory and experiences that he perpetually rehearsed in his painting over the previous twenty years – motifs from many years earlier being revisited in these drawings.

What made Wallis so important to Ben and Winifred (1893–1981) Nicholson and Christopher Wood (1901–1930) after they had first discovered him in 1928 was the manner in which Wallis distilled his experience into his work – revealed to them as an authentically produced aesthetic truth. He did not objectively transcribe and record; it was Ben Nicholson’s understanding of Wallis’s success at concretising his experiences that characterised the significance of Wallis’s work for him. In one respect his works are factual records, yet as representations they were not straightforwardly descriptive, but instead made to fit his memory as events made tangible. By the end of his life however, at the time of these sketchbooks, Wallis’s significance for Nicholson and his contemporaries such as Stokes had shifted markedly. In the late 1920s Wallis’s work reflected and reinforced Nicholson’s move towards a more naïve or ‘primitive’ way of painting that expressed truth and reality as he saw it. The art historian and critic Alan Bowness additionally suggested that Wallis ‘was not an isolated and eccentric figure, but someone who was every bit as necessary to English painters as the Douanier Rousseau was necessary to Picasso and his friends. When art reaches an over-sophisticated stage, someone who can paint out of his experience with an unsullied and intense personal vision becomes of inestimable value.’ (Alan Bowness, in Arts Council 1968, unpaginated).

Further reading

Sven Berlin, Alfred Wallis Primitive, London 1949.

Alfred Wallis, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1968.

Two Painters, Works by Alfred Wallis and James Dixon, exhibition catalogue, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin 1999

Andrew Wilson

August 2019

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

You might like

-

Alfred Wallis Houses at St Ives, Cornwall

?c.1928–1933 -

Alfred Wallis The Blue Ship

?c.1934 -

Alfred Wallis Wreck of the Alba

c.1938–9 -

Alfred Wallis Grey Book

c.1941–2 -

Alfred Wallis Lion Book

c.1941–2