In Tate Britain

Prints and Drawings Room

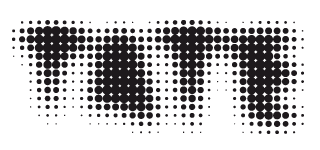

View by appointment- Artist

- David Wojnarowicz 1954–1992

- Medium

- Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper mounted on foam

- Dimensions

- Image: 200 × 250 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 2010

- Reference

- P79879

Summary

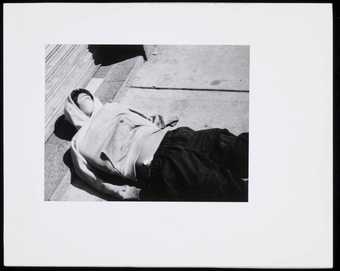

Untitled is a black and white photograph depicting a man lying on his back on a sandy beach. The camera is positioned at the top of the man’s head, looking horizontally down his body towards the waterfront. The man wears glasses and is topless, with his hands clasped on his chest in a relaxed posture. Aside from the tip of his left foot, his lower half cannot be seen, since the angle of the camera means that it is obscured by his upper body. A small wave is breaking at the shoreline and various areas of land, including at least one island, can be seen along the horizon.

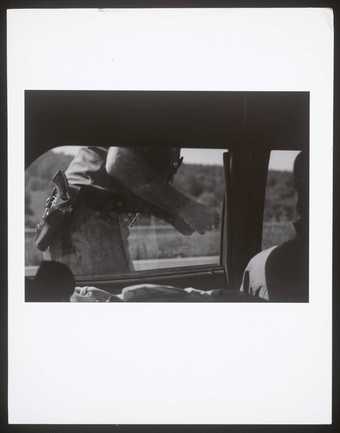

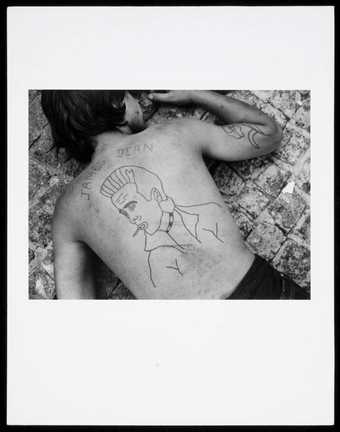

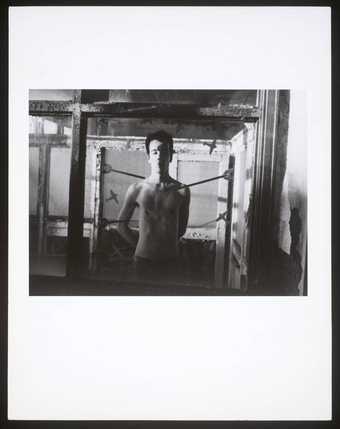

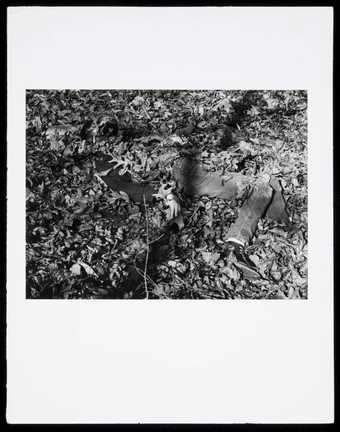

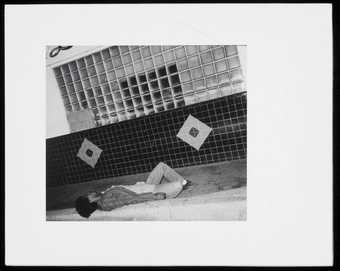

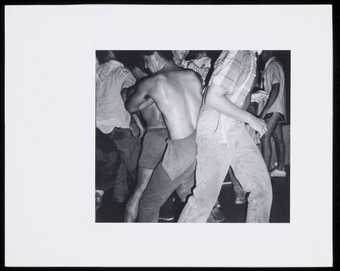

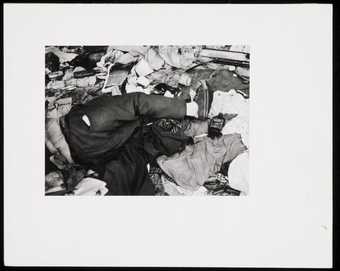

This photograph was taken by the American artist David Wojnarowicz on one of the many road trips he took around the United States and Mexico during the 1980s, starting in 1984. Thirty such photographs are held in the Tate collection (Tate P79858–P79887) and although they were taken while Wojnarowicz was travelling during the mid-1980s onwards, they are all dated 1988, perhaps indicating the year of their printing (Lotringer and Ambrosino 2007, p.97). All of the photographs in this group are identical in size and are mounted on foam.

Wojnarowicz first used photography as part of his artistic practice in 1978. However, during the early and mid-1980s he did not exhibit his photographs as artworks in their own right, instead using the pictures he took as sources for, and occasionally collage elements in, his paintings and multimedia works (see, for instance, Fuck You Faggot Fucker 1984, private collection). In 1988 he began making and exhibiting photo-collages, often incorporating photographs he had taken in previous years. Several of the many Untitled 1988 photographs were used in such collages, for instance in Spirituality (for Paul Thek) 1988–9. Wojnarowicz’s friend and collaborator, the photographer Marion Scemama, has noted that until he started collaging them in 1988, Wojnarowicz saw his photographs as ‘snapshot[s]’ and not artworks (Marion Scemama and Sylvère Lotringer, ‘Marion Scemama’, in Lotringer and Ambrosino 2007, p.128). The art historian Mysoon Rizk has connected Wojnarowicz’s increased interest from 1988 onwards in photography as a distinct art form with his then recent inheritance of ‘a well-equipped darkroom’ from the photographer Peter Hujar, who had died in 1987 (Mysoon Rizk, ‘Reinventing the Pre-Invented World’, in New Museum of Contemporary Art 1999, p.58).

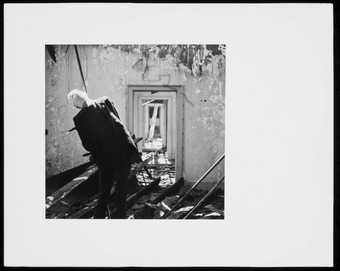

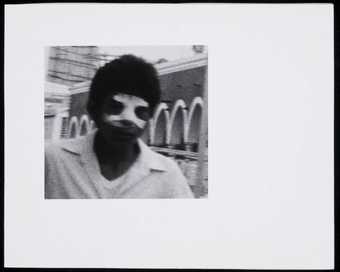

The ambiguity of many of the Untitled 1988 images is exacerbated by their lack of descriptive titles and their very closely cropped compositions. Parts of objects and figures are often excluded by the tight framing and in many cases only a limited indication of the spatial environment is provided. This may be connected to the fragmentary way in which Wojnarowicz worked when taking photographs, which the artist described in 1989:

everything I do with a camera is like a journal. I take fragments of things. If people were to look at my years and years worth of negatives, they would wonder what the hell was he shooting at? ... People wouldn’t know if they were looking at a piece of Ohio, or a piece of California, or a piece of the 12th Avenue Expressway. Yet, I can look at some of these contact sheets, and there can be something that’s so charged with a certain kind of energy or memory and smell and sight.

(Sylvère Lotringer and David Wojnarowicz, ‘Sylvère Lotringer / David Wojnarowicz’, in Lotringer and Ambrosino 2007, p.163.)

The Untitled 1988 photographs frequently depict people in the street and in crumbling buildings, and Wojnarowicz may have regarded them as images of an alternative view of America and Mexico during the 1980s, ones that better represented his experience than did those in the mass media. In 1991 the artist wrote: ‘If you look at newspapers you rarely see a representation of anything you believe to be the world you inhabit. This is called information control ... I believe I represent a different intention in what I point my camera toward. I have a desire to open up certain boundaries and release information that unites the psychic ropes that bind the ONE-TRIBE NATION’ (Wojnarowicz 1991, p.143). The cultural historian C. Carr has emphasised further this combination of creative subjectivity and documentation in Wojnarowicz’s work: ‘Art was [Wojnarowicz’s] way of witnessing. On some level, the work was about putting information out there, exposing what’s usually hidden and creating a cultural counterweight. Where the marginal are ignored, he would exalt them ... To him, it wasn’t politics, it was truth’ (C. Carr, ‘Portrait in Twenty-Three Rounds’, in New Museum of Contemporary Art 1999, p.69).

Further reading

David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives, New York 1991.

Fever: The Art of David Wojnarowicz, exhibition catalogue, New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York 1999.

Sylvère Lotringer and Giancarlo Ambrosino, David Wojnarowicz: A Definitive History of Five or Six Years on the Lower East Side, New York 2007.

David Hodge

January 2015

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- photographic(4,673)

- recreational activities(2,836)

-

- sunbathing(54)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- sunglasses(55)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- lying down(392)

- man(10,453)

You might like

-

David Wojnarowicz Untitled (Desire)

1988 -

David Wojnarowicz Untitled

1988 -

David Wojnarowicz Untitled

1988 -

David Wojnarowicz Untitled

1988 -

David Wojnarowicz Untitled

1988 -

David Wojnarowicz Untitled

1988 -

David Wojnarowicz Untitled

1988 -

David Wojnarowicz Untitled

1988 -

David Wojnarowicz Untitled

1988 -

David Wojnarowicz Untitled

1988 -

David Wojnarowicz Untitled

1988 -

David Wojnarowicz Untitled

1988 -

David Wojnarowicz Untitled

1988 -

David Wojnarowicz Untitled

1988 -

David Wojnarowicz Untitled

1988