Amedeo Modigliani’s practice of using previously painted canvases as supports for new works is well known. The collector Henry Pearlman, for instance, recounted that in 1915 Modigliani salvaged another artist’s canvas stored in the studio of Russian sculptor Leon Indenbaum in order to paint a portrait of Indenbaum (C91).1 Having identified a still life he thought ‘could be sacrificed’, Modigliani ‘scraped off the heavy paint and commenced’. X-radiograph images of the portrait back up Pearlman’s story, revealing evidence of the still life beneath.2 Similarly, X-radiographs reveal that Modigliani’s portrait of the poet and playwright Jean Cocteau of 1916 (C106) was painted over a self-portrait by Moïse Kisling that featured his wife Renée and their dog.3 Modigliani turned the canvas 90 degrees to paint Cocteau’s portrait during a friendly portrait-painting competition between himself and Kisling.

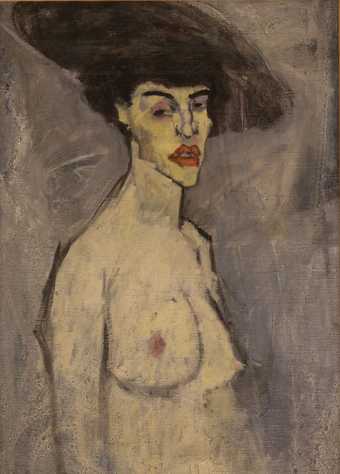

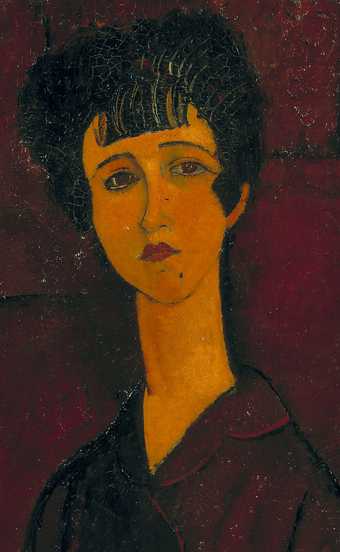

Fig.1

Bust of Nude Woman with Hat (recto) 1908

Oil on canvas

720 x 490 mm

Hecht Museum, University of Haifa, Haifa

C7a

Photo: Shay Levy

Fig.2

Maud Abrantes (verso) 1908

Oil on canvas

590 x 460 mm

Hecht Museum, University of Haifa, Haifa

C7b

Photo: Shay Levy

However, even before these instances, the artist was clearly reusing canvases. In some of his earliest works, such as two from 1908 now in private collections, Bust of a Young Girl (C10) and Nude Study (C8), Modigliani seems to have used works by other artists, turned 180 degrees, as supports. He also painted multiple works on a single canvas, as well as turning it over and upside down and painting on the reverse, such as in the case of Bust of Nude Woman with Hat (C7a, recto; fig.1) and Maud Abrantes 1908 (C7b, verso; fig.2). In these examples, he was seemingly unconcerned with covering the original image, as the underlying figures remain clearly visible to the naked eye, down to the colour of their hair and lips.

Modigliani reportedly used any supports and materials that were at hand. This practice was typical of his peer group and some of Modigliani’s own paintings were painted over by his contemporaries, including by Pablo Picasso.4 Modigliani’s friend Chaïm Soutine preferred to work over old paintings that he bought from antique dealers and flea markets.5 Because Modigliani was known to scavenge for stones and wood for carving, it is reasonable to assume he had a similarly open-minded approach to finding two-dimensional supports.6 Perhaps, in this spirit, he searched out second-hand canvases for his paintings.7 During the early years of his career, Modigliani painted on various kinds of support, from cardboard to canvas. The artist’s creativity and flexibility in this regard were largely influenced by his precarious financial situation, although an interest in the aesthetic qualities of second-hand canvases likely also played a part. The sculptor Jacques Lipchitz recalled that Modigliani worked in any spot where he could set up his easel for the afternoon in his sitter’s quarters. He often painted in Kisling’s big studio in Montparnasse, Paris, where he found varied subjects for portraits in the personalities who came from all over the city to congregate there. He also painted in other artists’ studios, using their supplies in addition to or instead of his own.8

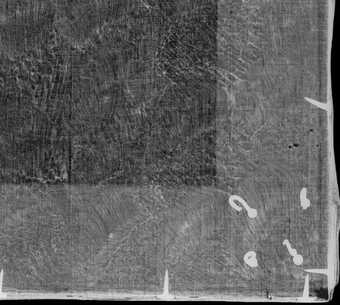

This article considers three works with underlying images discussed briefly in the Burlington Magazine in 2018, alongside two further works.9 Portrait of a Girl c.1917 (Tate; C118) was included in the Burlington series introductory essay and illustrated with an X-radiograph;10 and Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz 1916 (Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago; C161) and The Pretty Housewife 1915 (Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia; C60) were discussed in the Burlington series in the context of Modigliani’s Paris portraits of 1915–17.11 One of the questions that arose from this initial study related to how Modigliani used the previously painted surfaces, and whether he chose to incorporate the underlying colours in his paintings or rather painted an interim layer of white ground over the existing paint surface to allow for a fresh start. The current paper explores this issue in more detail, after further in-depth analysis into these works and with the benefit of a growing knowledge of the artist’s techniques. The two other paintings we discuss here are Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix 1909 (C12) and Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window 1913 (C40), both in the collection of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen. The analysis of these two paintings is the result of a two-year research project into twenty-eight Modigliani paintings and one sculpture in French national museums. Our French colleagues have generously added their discoveries of paintings beneath the visible surface of Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix and Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window to this study.12

The five case studies span 1909 to c.1917 and are presented here in the chronological order that Modigliani created them, as given in Ambrogio Ceroni’s publication of 1970.13 As we carried out this research, we found that in some instances the texture of the paintings indicated the presence of something painted below the surface of the visible image. In others, the hidden images were discovered only after technical examination such as X-radiography, infrared imaging and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) elemental mapping.14 Taken together, these canvases give a fascinating insight into Modigliani’s innovative and artistic response to underlying paintings.

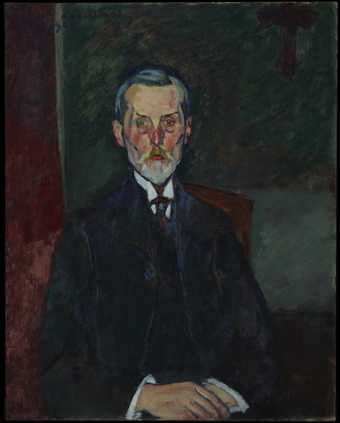

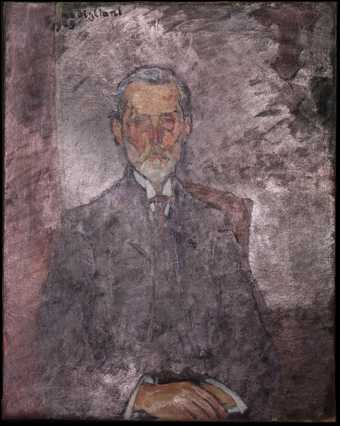

Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix 1909

Fig.3

Amedeo Modigliani

Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix (Jean-Baptiste Alexandre au crucifix) 1909

Oil on canvas

920 x 730 mm

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen, Rouen

C12

© C2RMF / Philippe Salinson

In 1909, Modigliani received his first official commission: to paint Jean-Baptiste Alexandre, the father of his friend and patron Paul Alexandre.15 Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix (fig.3) is signed and dated ‘Modigliani 1909’ at the upper left. It was part of Paul Alexandre’s collection and entered the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen in 1988 as part of the Blaise and Philippe Alexandre bequest. Two preparatory drawings for this painting are known. They were made during the portrait sittings; one is in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen and the second is in a private collection.16

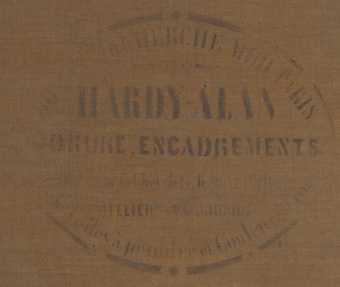

Fig.4

Amedeo Modigliani

Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix, detail of the Hardy-Alan artist canvas supplier stamp applied to the back of the canvas

© C2RMF / Philippe Salinson

The painting is executed on a relatively coarse, tightly woven canvas, with an average thread density of 22.5 horizontal (warp) and 17.5 vertical (weft) threads per centimetre. It measures 92 by 73 centimetres, which corresponds to a standard-size figure 30 canvas.17 The edges of the canvas remain unpainted, which suggests that the dimensions are original. It is attached to a five-member stretcher with wooden keys at each joint. On the back of the canvas, at the lower centre, is the artists’ supplier’s stamp ‘Hardy-Alan’ (fig.4). Some parts of the stamp are difficult to read, but the following text can be transcribed: ‘36 RUE DU CHERCHE MIDI PARIS / HARDY-ALAN / DORURE, ENCADREMENTS / … Chevalet … / ATELIERS … / … Toiles à peindre et Couleurs fines’. The Guide Labreuche, which compiles artists’ material suppliers in Paris from 1790 to 1960, mentions that this business moved from 36 rue du Cherche-Midi to 92 Boulevard Raspail in Paris on 15 July 1907.18 It is likely, therefore, that the canvas used for the painting was bought before the supplier moved premises in 1907, but it cannot be ruled out that canvases with that stamp continued to be sold for a time after the business relocated.

A thick lead white ground layer was applied to the canvas. It partially reaches every edge, with the exception of the lower one.19 This suggests that the canvas was not primed commercially but possibly by Modigliani himself. The signature and the date were applied in dark blue at the upper left, on a mainly dark green background that was already dry.20 The paint used for the signature is relatively thick and there are gaps in the letters where the colour skips over the surface. The same colour is used for the date, but the paint is more fluid and was probably diluted using a solvent.

Fig.5

Amedeo Modigliani

Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix, specular reflected light photograph indicating the thickness of the varnish

© C2RMF / Philippe Salinson

The painting is covered by a thin varnish layer that has yellowed slightly. Photographs taken under ultraviolet (UV) light and with specular reflected light reveal that the thickness of the varnish layer across the painting is inconsistent (fig.5). Notably, Jean-Baptiste Alexandre’s hands seem to be partially unvarnished. An area under the cross, which appears near the upper right edge of the painting, appears also to be less thickly varnished.21

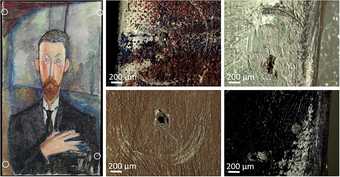

Fig.6

Amedeo Modigliani

Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix, composite image of MA-XRF elemental distribution maps showing lead (Pb-L and Pb-M, corresponding to lead at the surface), zinc (Zn), barium (Ba-L), calcium (Ca), cobalt (Co), chromium (Cr), iron (Fe), mercury (Hg), tin (Sn), and copper and arsenic (Cu and As). The copper and arsenic elemental maps are identical and only the copper map is represented here

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

The palette used to paint the portrait of Jean-Baptiste Alexandre is more varied than it may initially appear (fig.6).22 Modigliani used both lead- and zinc-based white pigments, exploiting their different qualities. For the head, he painted in the shape of the face using a lead white-based paint, which tends towards flat and even coverage, and the facial features with a zinc-based paint, which has a brighter hue and retains texture and brushstrokes more readily. In both cases the white was mixed with coloured pigments.23 The colour of the skin tones was obtained mainly using vermilion. An iron-based pigment was used to highlight the outlines of the hands and a few details in the face. The background can be separated into three distinct areas of different colours: red (the curtains and upholstery at the left of the composition and behind the figure); green (the area around the head); and blue (the area to the right of the sitter’s shoulders). However, these areas of colour are made up of complex layers. The red areas are mainly made with red lake on a tin-based substrate and vermilion, possibly with a small amount of iron-based pigment. A cobalt blue layer was applied over the red layers at the upper left. A green layer, also applied over the red area, is a chromium-based green pigment. The presence of an iron-based pigment is related to a red/brown layer located under the green and partially visible in some areas. Along the right side of the head, a cobalt blue layer was applied over the green layer of the background, almost as if Modigliani tried to hide a pentimento – a change made during the process of painting the image. The cross was painted using cobalt blue, bone black, iron-based pigments and vermilion. The brown chair was executed with vermilion mixed with an iron-based pigment (earth and/or ochre) and a small amount of a chrome-based pigment. Modigliani’s skill as a colourist is particularly evident in the dark jacket that appears black but comprises a range of pigments including bone black, Prussian blue, cobalt blue, a green chrome-based pigment and a small amount of red lake and vermilion, all of which contribute to the creation of fine shades and an illusion of depth.

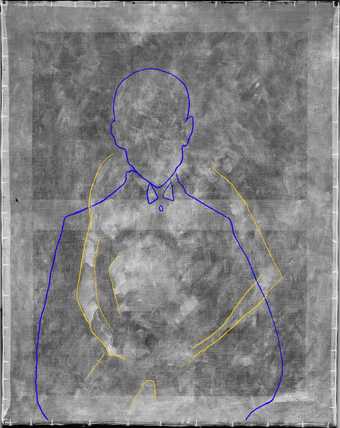

Fig.7a

Amedeo Modigliani

Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix,

X-radiograph

© C2RMF / Philippe Salinson

Fig.7b

Amedeo Modigliani

Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix, X-radiograph with blue lines indicating the outlines of the final portrait and yellow lines corresponding to the sketch of the underlying portrait

© C2RMF / Philippe Salinson, blue and yellow lines by Anaïs Genty-Vincent

Fig.8a

Amedeo Modigliani

Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix, X-radiograph showing surface roughness and brushstrokes linked to the underlying composition, with red boxes indicating the locations imaged in figs.8b–d

© C2RMF / Philippe Salinson

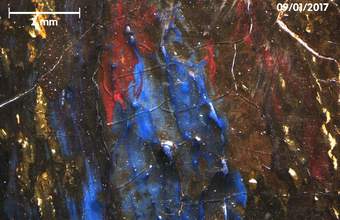

Fig.8b

Amedeo Modigliani

Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix, detail in raking light showing surface roughness and brushstrokes linked to the underlying composition

© C2RMF / Philippe Salinson

Fig.8c

Amedeo Modigliani

Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix, detail of the painting in raking light showing surface roughness and brushstrokes linked to the underlying composition

© C2RMF / Philippe Salinson

Fig.8d

Amedeo Modigliani

Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix, micrograph of the paint surface showing surface roughness and brushstrokes linked to the underlying composition

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

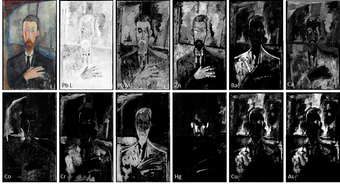

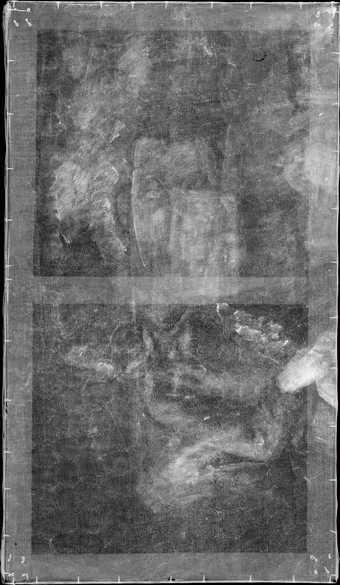

The figure of Jean-Baptiste Alexandre is barely discernible in the X-radiograph (figs.7a–b); the most visible areas are his white collar and his head. However, the X-radiograph reveals an underlying portrait. The outlines of the underlying figure’s body are particularly defined, though the position of the head is unclear. Some highlights on the arms are clearly visible on the X-radiograph, suggesting the use of lead white. There is also some indication of the underlying painting upon close examination of Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix: roughness in the surface of the sitter’s dark jacket corresponds to thick impasto layers beneath (figs.8a–d).

The composition beneath the portrait of Jean-Baptiste Alexandre is difficult to read. It could be a torso of a naked woman – seated and possibly pregnant – or perhaps the torso of an overweight older man. More probably, it could relate to Modigliani’s painting Young Gypsy (private collection; C28). Like the figure visible in the X-radiograph, the model in Young Gypsy sits with legs slightly apart, and the rounded abdomen and position of the arms and the hands are similar. Moreover, the highlights in the arms described above are comparable in technique to those of the Young Gypsy.

Fig.9a

Amedeo Modigliani

Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix, the painting in visible light, with a red rectangle showing the area of the SWIR detail presented in 9b

© C2RMF / Philippe Salinson

Fig.9b

Amedeo Modigliani

Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix, an SWIR reflectance hyperspectral image: minimum noise fraction (MNF) 2 image of a small area around the sitter’s hands, after a 180-degree rotation and the use of an MNF algorithm

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

Fig.9c

Amedeo Modigliani

Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix, an SWIR reflectance hyperspectral image: principal component analysis (PCA) 3 image of the whole data set treated by a PCA algorithm

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

Fig.10

Amedeo Modigliani

Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix, MA-XRF combined map (detail, rotation of 180 degrees) with mercury (in red), copper (in green) and iron (in blue). Copper and arsenic elemental maps are identical and only the copper map is shown

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

Macro X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF) and short-wave infrared (SWIR) reflectance hyperspectral imaging reveal the presence of a second underlying painting beneath Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix (figs.9a–c). It is a portrait of a bearded man, located upside-down near the hands of Jean-Baptiste Alexandre. While the head is painted in detail, the body is incomplete. It could be a first portrait of Jean-Baptiste Alexandre that Modigliani started and then stopped. The SWIR image reveals only a curve related to the neck (painted with an infrared absorbing material). MA-XRF imaging gives some indication of the pigments used in the portrait, but the additional overlying layers of paint inhibit the detection of the elements of the pigments in lower layers. It seems that the head was painted using an iron-based pigment, vermilion and emerald green (fig.9b), and that some brushstrokes in the background are related neither to the current portrait nor to the underlying portrait revealed by X-radiography. This implies that the various layers contributing to the current visible background contain an iron-based pigment, vermilion, emerald green, as well as cobalt blue (mainly visible in the lower left in the mercury, copper arsenic, iron and cobalt MA-XRF elemental distribution maps and in the combined map; fig.10).

Figs.11a–b

Amedeo Modigliani

Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix, two cross-sections in visible light (brightfield)

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

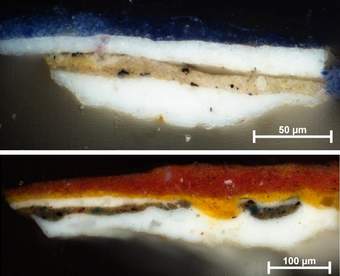

Cross-sections are inconclusive regarding the presence of ground layers between the three compositions (figs.11a–b). No intermediate ground layer is visible in the first cross-section (fig.11a), but in the second cross-section (fig.11b), a layer made of lead white and barite is present either between the first and the second underlying composition, or between the second underlying image and the final portrait. However, it is difficult to assess whether this white middle layer, identified in only one of the two cross-sections, signals an intermediate ground.24

The use of complementary multi-analytical techniques has unveiled the existence of two underlying paintings beneath the portrait of Jean-Baptiste Alexandre and helped to discern the order in which they were made.25 The possible nude portrait revealed by X-radiography was almost certainly painted first. The canvas was then rotated 180 degrees to paint the portrait of the bearded man that was detected by MA-XRF and SWIR analyses. Finally, the canvas was rotated 180 degrees again before Modigliani made his portrait of Jean-Baptiste Alexandre. Modigliani was commissioned by the sitter at a cost of 500 francs.26 It is perhaps surprising, therefore, that Modigliani reused a previously painted canvas to honour this, his first official commission.

The results of the technical examination do not allow for a firm attribution of the underlying paintings, but the upside-down portrait of the bearded man could be an earlier version of Modigliani’s portrait of Jean-Baptiste Alexandre, as they share a beard and a pronounced brow bone. The presence of the artists’ supplier’s stamp ‘Hardy-Alan’ could suggest that the portrait beneath the surface, possibly of a nude, was executed before 15 July 1907, when the supplier changed his business address. However, we do not know how long the artist had the canvas before he began painting, or indeed if the supplier kept the previously stamped canvases in stock until his inventory was sold. The composition of the nude portrait cannot be identified with certainty, but it recalls that of the Young Gypsy (C28), which Ceroni dates to 1909.27

Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window 1913

Paul Alexandre met Modigliani at the end of 1907 and was his only known buyer until 1914. That year Alexandre was sent to the front to fight during the First World War, and the pair never resumed contact thereafter. The portrait of Paul’s father (Jean-Baptiste Alexandre with a Crucifix) and that of his brother Jean Alexandre (C16), together with five portraits of Paul himself (C13, C14, C15, C31 and C40) remained in the family’s collection.28 During this same period, from 1909 to 1913, Modigliani made at least fourteen drawings of his young patron.29

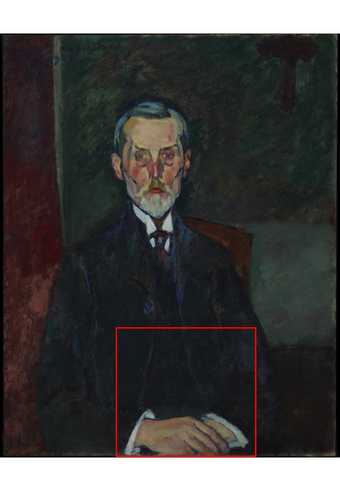

Fig.12

Amedeo Modigliani

Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window (Paul Alexandre devant un vitrage) 1913

Oil on canvas

810 x 456 mm

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen, Rouen

C40

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

Fig.13a

Amedeo Modigliani

Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window, detail in visible light of the strainer with four nails at the corner

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

Fig.13b

Amedeo Modigliani

Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window, X-radiograph of the same area as is shown in fig.13a

© C2RMF / Philippe Salinson

Fig.14

Amedeo Modigliani

Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window, composite image showing micrographs of the four pinholes visible at each corner of the painting. The image on the left shows the portrait with white circles indicating the pinholes’ exact locations

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent and Gérald Parisse

Modigliani painted Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window (fig.12) between mid-November 1913 and the beginning of 1914, although the painting is neither signed nor dated.30 It is painted on a thin, tightly woven canvas, with an average thread density of 22.9 horizontal (warp) threads and 22.9 vertical (weft) threads per centimetre. Its dimensions, 81 by 45.6 cm, do not correspond to any standard format.31 The painting is attached to a five-member strainer that is held together by four nails at each corner (figs.13a–b).32 Close examination of the painting surface reveals the presence of push-pin holes at each corner (fig.14). The area that would have been under the pin is painted and it can be seen that the pin was pressed in when the paint was still soft, resulting in some surface damage where the edges of the pins scraped into the paint. Photographs of the artist’s studio show that he sometimes pinned canvases directly to the wall. These holes and markings in the wet paint could also have been made by tacks that Modigliani used as spacers to stack wet paintings against one another.

Fig.15

Amedeo Modigliani

Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window, detail of the Pascal Coccoz artists’ materials supplier stamp on the horizontal crossmember

© C2RMF / Gérald Parisse

An artists’ supplier’s stamp that reads ‘PASCAL COCCOZ / 12, rue de Douai’ is visible on the horizontal crossmember of the strainer (fig.15). Similar stamps have been noted on other stretchers and strainers used by Modigliani.33 The Guide Labreuche lists an ‘A. Coccoz’ in 1914 as successor of ‘F. Perrod’ and ‘Revel et Coccoz’, located at 33 bis, Boulevard de Clichy.34 Although there is an inconsistency in the forename initial given and in the address, the two addresses are located only 260 metres away from each other.

A white ground layer is visible in some areas of the painting and also on the lower and upper tacking margins, which indicates that the canvas had a commercial priming layer. The left edge is covered by a brown wash, while the right is painted. The ground layer is partly missing in the cross-sections, but it is at least 100 micrometres thick and composed of lead white.35 A very thin varnish layer was applied, probably with a brush. Its thickness varies from 5 to 17 micrometres. Ultraviolet light photography reveals that the painting is very well preserved. Retouching is visible on the edge and at the top right, where the canvas was slightly torn. The tear was fixed with a small patch (around 4 by 4.5 centimetres) that is visible on the reverse of the canvas.

Fig.16

Amedeo Modigliani

Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window, composite image of MA-XRF elemental maps showing the elemental distribution of lead (Pb L and Pb M, corresponding to lead at the surface), zinc (Zn), barium (Ba), calcium (Ca), cobalt (Co), chrome (Cr), iron (Fe), mercury (Hg), and copper (Cu) and arsenic (As)

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

As in the portrait of Jean-Baptiste Alexandre, both lead and zinc white pigments were identified in the palette of Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window (fig.16).36 The spatial distribution of the zinc and barium, however, are completely different, which indicates that they are not associated within the single compound lithopone. It seems that Modigliani used three kinds of white pigment for the paint layers of the portrait of Paul Alexandre: lead white, zinc white and barite. The red of the curtain at the top left of the composition may contain a calcium-based red lake. Under the red lake, chrome-based green and Prussian blue paint layers are visible. The blue highlight that traces the edges of the curtain and window is cobalt blue. Otherwise, the background is mainly composed of emerald green and chromium-based pigment for the upper part, and ochre for the lower-left corner. The grey tones are probably made with bone black. However, the presence of calcium could also be due to the use of calcium carbonate or calcium sulphate. Paul Alexandre’s dark jacket was painted using a wide variety of pigments such as bone black, emerald green, chromium green pigments and Prussian blue mixed with barite. The skin tones of the face are painted using lead and zinc white, vermilion and an iron-based pigment; a calcium-based pigment (probably an extender, either calcium sulphate or calcium carbonate) is used for the circles around the eyes. In contrast, the hand is painted using only iron-based pigment, except the two outlines which are painted with vermilion. The skin tones of the face are more finely worked than those of the hand, a characteristic that is often found in Modigliani’s portraits.

The presence of several red ochre dots under Paul Alexandre’s hand may relate to Modigliani’s sculpture practice. The painting was executed in late 1913, towards the end of the two-year period during which the artist focused on sculpture. His Female Head 1911–13 (Centre Pompidou, Paris; Ciii) may give us some indication as to his technique as a sculptor.37 There is a face carved on each side of the stone block: one is more developed, with the chin and neck modelled in high relief and some fine detail around the eyes and hair; the other shows the initial outlines of the eyes, nose and mouth carved into an otherwise flat surface.38 On the less finished side, outlines of the head are marked with holes made with a point chisel. In addition to the painting of Paul Alexandre, two paintings from 1915 – Woman’s Head (Rosa Porprina) (Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Milan; C84) and Portrait of Madame Othon Friesz, La Marseillaise (Denver Art Museum, Denver; C85) – show the use of dots to establish the outlines of forms. A string of black painted dots also appears in the double portrait of Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz 1916 at the inner edge of Jacques’s hairline, as discussed later in this article.

Fig.17a

Amedeo Modigliani

Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window, MA-XRF mercury map showing the identification of a hidden architectural element through the window at the upper edge of the painting’s background

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

Fig.17b

Amedeo Modigliani

Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window, detail of X-radiograph, showing the identification of a hidden architectural element through the window at the upper edge of the painting’s background

© C2RMF / Philippe Salinson

Fig.18a

Amedeo Modigliani

Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window, pentimento on the right shoulder: SWIR reflectance hyperspectral PC2 image obtained through a principal component analysis of the data set

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

Fig.18b

Amedeo Modigliani

Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window, pentimento on the right shoulder: XRF combined map showing iron (Fe) in red, zinc (Zn) in green and lead (Pb-M, surface layer) in blue

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

The portrait of Paul Alexandre shows evidence of three pentimenti – underlying images that suggest changes made during the painting process. First, the MA-XRF mercury map reveals that there was previously an architectural feature that was visible through the window in the background (fig.17a). Horizontal lines linked to the building are also discernible on the X-radiograph (fig.17b); it was composed (at least in part) of a layer rich in vermilion; a highlight that incorporates iron pigments is visible under the lower horizontal lines. This suggests that the architectural feature was probably executed in a brick colour. The second pentimento is located around the red curtain. Blue and green layers are visible beneath the red, indicating that the background continues under the red triangle, which was added later. This second pentimento is mainly visible in the iron, cobalt, copper/arsenic and chromium elemental maps. The third pentimento is at the sitter’s right shoulder and shows that Modigliani first painted the shoulder a little higher on the canvas, before covering it with an eye-catching blue highlight (figs.18a–b). This was detected in the SWIR images and on some of the MA-XRF elemental distribution maps. Modigliani probably made this modification to achieve greater symmetry in Paul Alexandre’s torso.

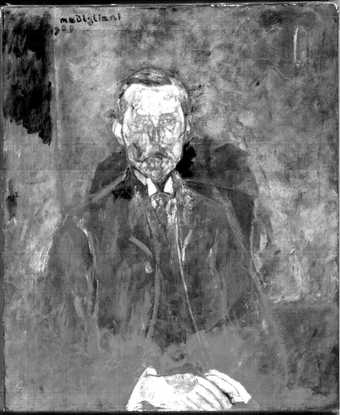

Fig.19

Amedeo Modigliani

Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window, X-radiograph

© C2RMF / Philippe Salinson

Fig.20

Amedeo Modigliani

Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window, X-radiograph after a 90-degree clockwise rotation, surrounded by visible light photographs of the tacking margins

© C2RMF / Philippe Salinson, Gérald Parisse and Anaïs Genty-Vincent

Figs.21a–b

Amedeo Modigliani

Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window, two cross-sections in visible light (brightfield)

© C2RMF / Anaïs Genty-Vincent

The X-radiograph reveals a painting of a man beneath the portrait of Paul Alexandre, after a 90-degree clockwise rotation (figs.19 and 20). No elements related to the underlying composition are discernible in the MA-XRF elemental distribution maps, with the exception of the hand, which is visible in the XRF mercury map (see fig.16). The cross-section of micro-samples taken from a blue area at the edge of the painting reveals an intermediate varnish layer (fig.21a), indicating that the first painting was already varnished before Modigliani used it to paint the current composition featuring Alexandre. A second ground layer, composed of lead white, was probably applied by Modigliani on top of the underlying painting. In cross-sections of the paint film there is a lower ground layer that is covered with a pigmented layer of paint which has a thin dark line of varnish at the top. Over this is the bright white second ground layer covered with the bright blue (fig.21a) or the brownish orange (fig.21b) of the surface layer. The underlying painting is visible on the tacking edges and was not covered by the additional ground layer, which means that it was already stretched before Modigliani applied the fresh white surface to begin his new painting.

The underlying composition appears to have been painted in a horizontal format. The tacking margins along the shorter edges of the painting in its current format are unpainted, which indicates that the dimension of the short edge, at 81 cm, did not change and would have been the vertical dimension of the painting beneath. However, the underlying composition, around the sitter’s hands, continues on to the current right tacking margin of the painting, indicating that the canvas was cut on at least one side before the application of the second ground layer. The dimensions of the underlying composition were thus probably around 48.5 cm (46.5 plus around 2 cm of tacking margin) by no more than 81 cm. The dimension of the longer side, at 81 cm, corresponds to a no.25 format in the French system of standardised stretchers and canvases. Thus, the underlying painting could have been executed on a no.25 marine (81 by 54 cm), no.25 paysage (81 by 60 cm) or no.25 figure (81 by 65 cm) canvas.

The attribution of the underlying composition is not conclusive. However, in Modigliani’s oeuvre, the use of a horizontal format in or before 1913 is unusual. Indeed, with the exception of his reclining nudes of 1917–19, all known Modigliani paintings are vertical in format. When turned 90 degrees clockwise, it is clear that the tacking margin at the lowest edge of the painting, shown in visible light around the X-radiograph in fig.20, is painted in muted tones and that the painted shapes correspond exactly to the edges of the image in the X-radiograph, which is a composition in landscape format. The style and colours of this landscape composition are not reminiscent of Modigliani. In addition, the fact that the previous painting was already varnished and that an intermediate ground layer was applied may indicate that it is not a painting by Modigliani. He seems to have obtained an old painting and cut it up to be stretched onto the current strainer. He then appears to have covered the front of the painting with a white ground before he started his own painting, leaving the edge of the underlying painting visible along the tacking margin. This has been recorded as a modus operandi for Soutine and could well have been adopted by Modigliani for want of new canvases.39

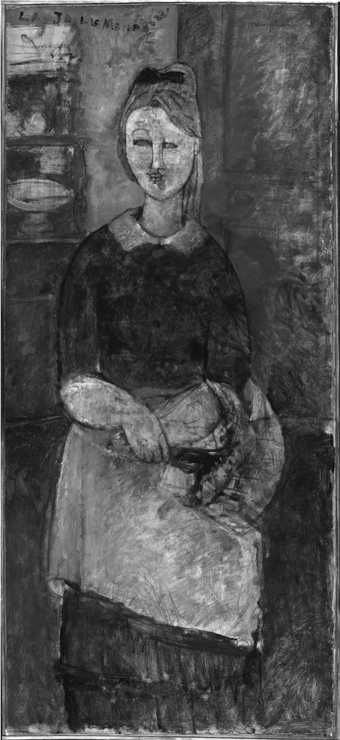

The Pretty Housewife 1915

Fig.22

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife 1915

Oil on canvas

1105 x 498 mm

Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

C60

Public domain

Fig.23

Paul Guillaume in his home, Paris, c.1916–17, with Modigliani’s The Pretty Housewife 1915 hanging on the wall behind him

Archives Alain Bouret, Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris

Photo: Dominique Couto

© RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Fig.24a

Amedeo Modigliani

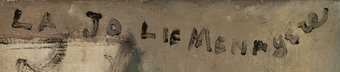

The Pretty Housewife, detail in normal light of the painting’s title at the upper left of the composition

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

Fig.24b

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, closer detail of the painting’s title showing the wet-into-wet application of the black paint over the grey background

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

Fig.25

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, detail in normal light of the artist’s signature at the upper right of the composition

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

The Pretty Housewife (fig.22) in the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia appears in a 1915 photograph of the art dealer Paul Guillaume in his apartment (fig.23) and was acquired from Guillaume by Albert C. Barnes in March 1923.40 The title of the painting is inscribed in the upper left with bone black paint, wet-into-wet, with a narrow, flat brush (figs.24a–b).41 The artist’s signature is delineated with thinned black paint on top of the dry painting (fig.25). Both inscriptions lie under non-original natural resin varnishes.

Modigliani’s narrow, vertical composition contains a single female figure within an interior space defined by the cursory depiction of a cupboard on the left and a door on the right; browns, greys and black dominate the palette. The seemingly simple composition and limited colour palette, typical of Modigliani’s early work, conceal a much more complicated construction: at least two previous painted layers lie underneath The Pretty Housewife. The 2017 discovery of these earlier paintings spurred the current technical study that aimed to determine whether they could be attributed to Modigliani.42 The investigation also examined the ways in which using a previously painted canvas may have affected Modigliani’s creative process.

Fig.26

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, X-radiograph showing the prominent semi-circular shape from the earliest underlying painting

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

The earliest underlying image can be seen in an X-radiograph of The Pretty Housewife, which contains shapes that do not correspond to the final painting (fig.26).43 They include a prominent vertical semicircle in the middle of the canvas, several rough rectangles in the lower half, and other non-distinct shapes and irregular patterns throughout.44 Many of these shapes must have been painted rather thinly or have been scraped down by Modigliani before starting his composition, as their texture is no longer discernible on the present surface. Only the upper arch of the semicircle is visible as a faint ridge close to the proper left shoulder and collar of the sitter. The symmetry and flatness of this shape suggest an architectural feature, the orientation and prominence of which imply a horizontal format for the earlier composition, both of which are atypical of Modigliani’s work prior to 1915. This first layer, therefore, was most likely painted by someone else.

Fig.27a

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, infrared reflectogram

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

Fig.27b

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, infrared reflectogram with the underdrawing indicated in red

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

Fig.27c

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, infrared reflectogram detail of the lower centre of the apron showing a candy-cane shape

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

Fig.28

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, the painting in visible light (top left) and MA-XRF elemental maps showing the distribution of lead (Pb L and Pb M), barium (Ba), zinc (Zn), mercury (Hg), copper (Cu), arsenic (As), cobalt (Co), chromium (Cr), Iron (Fe) and calcium (Ca)

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

Fig.29

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, detail in raking light revealing the texture of the lower paint layers underneath the proper left arm and basket, including diagonal strokes

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

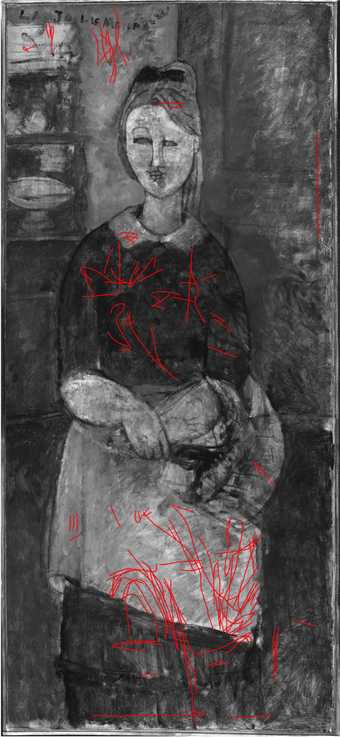

The second, or intermediate, painting is indistinguishable in the X-radiograph but is suggested by the presence of an underdrawing that does not correspond to The Pretty Housewife. Revealed by infrared reflectography, this underdrawing comprises a number of indecipherable lines (figs.27a–c).45 The drawing appears to relate to layers of paint laid on top, which are visible in the MA-XRF maps of the elements zinc, cobalt, mercury, copper and arsenic, implying the use of the pigments zinc white, cobalt blue, vermilion and emerald green respectively (fig.28).46 The elemental maps do not reveal a recognisable image; however, the distribution of emerald green suggests some intentional brushwork, including a candy-cane shape at the centre of the lower edge. This shape aligns with a group of underdrawing lines, suggesting that the composition of a second painting was planned out. The interrupted quality of the thin, carbon-containing lines of this sketch indicates that it was created with a dry medium, such as graphite pencil, applied over the already dry first painting. Another passage of the underlying emerald green-containing paint is defined by an obtuse angle in the lower right of the canvas. It is signalled on the painting’s surface in an array of straight brushstrokes that originate above the woman’s clasped hands and sweep diagonally down towards and through her basket (fig.29).

Fig.30

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, detail of the background in raking light showing the texture created by the vertical and diagonal brushstrokes in the lower paint layers

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

Fig.31

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, detail in raking light showing impasto from the lower paint layers in the area below the woman’s clasped hands

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

The map of zinc is dominated by an unidentifiable vertical shape on the left, lively and somewhat haphazard brushstrokes of varying thickness throughout, and some seemingly deliberate scrawls in the upper right corner and elsewhere in the right half of the painting. This zinc-based layer is also partially visible in raking light, in the well-defined brushstrokes in the background on each side of the figure (fig.30) and in an additional area of impasto just below the housewife’s proper right hand (fig.31). The elemental maps of zinc and copper/arsenic also suggest that the zinc-rich paint lies on top of the emerald green layer.47

Although the shapes and pigments revealed by infrared reflectography and elemental analysis provide only a partial understanding of the intermediary underdrawing and paint layers, they disclose enough to suggest that they are not part of a planned composition by Modigliani, since their nondescriptive nature does not fit within his representational style and his interest in portraiture.

Further study of the X-radiograph of The Pretty Housewife provides clues as to how the artist may have approached this recycled support. Computer-generated patterns of the canvas weave reveal the presence of cusping along the upper and lower edges and less pronounced cusping along the sides.48 This is also evident upon close examination of the surface: along the two longer sides, the underlying paint continues beyond the edges of the Pretty Housewife composition, suggesting that the canvas was removed from its original support and stretched onto a smaller one at some point after it had been painted. In contrast, the upper and lower turnover edges likely retain their original position, as suggested by the feathering of all paint layers towards these edges and the presence of some unpainted ground within the image plane of The Pretty Housewife.

Since the first underlying image on this canvas was probably horizontal, and since all of Modigliani’s earlier paintings are vertical and narrow, it is likely that he changed the format of the reused canvas by stretching it onto a smaller support and turning it 90 degrees from its original orientation in preparation for painting The Pretty Housewife. It must also be noted that the current size of the painting may differ slightly from that established by Modigliani, because the painting was lined and stretched on a new stretcher in the late 1920s or early 1930s after its acquisition by the Barnes Foundation.49 Neither the size of the current stretcher nor the outer boundaries of the final picture correspond to the nineteenth-century French standardised system of commercially available stretchers and prepared canvases.

It appears that Modigliani adopted this used canvas due to convenience or financial constraint rather than because of its format or working properties. Nevertheless, for the sake of cataloguing the types of canvases that the artist painted on, it is worth mentioning that the fabric is of a medium weight, even and open plain weave. The average thread density is 12.4 threads per centimetre in the horizontal (warp) direction and 15.6 threads per centimetre in the vertical (weft) direction.50 The even and uniform density of the white lead-containing ground seen in the X-radiograph indicates that the ground layer was likely commercially applied.51

Examination under magnification further illuminates Modigliani’s approach. He applied his oil paint in relatively thin layers with occasional use of thicker impasto.52 While no graphite or charcoal underdrawing for The Pretty Housewife was rendered visible in the infrared photograph (see figs.27a–c), Modigliani delineated many of the figure’s compositional elements with black paint before building up colour and form. Most of these lines are partially or fully concealed by the upper paint layers, but are visible under magnification in the hair and facial features. In some areas, such as at the tip of the nose and nostrils, the outline is reinforced on top of the skin tones using black, blue and red paint. This suggests that Modigliani not only relied on these lines to plan the composition, but that they are a central feature of the finished painting. He painted the face and hair of the sitter first, before moving on to her clothing and the background. Judging by the X-radiograph and other analyses, the artist did not make any major changes to the composition to arrive at the final image.

Fig.32

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, detail of the black paint over the white collar, showing beads of diluted black paint that was sponged over the white paint

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

Fig.33

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, detail of the background area to the left of the figure’s hips showing peaks and ridges of green paint that was sponged over the grey paint

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

Fig.34

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, detail of the cupboard showing scraping through the thin upper layer of brown paint to reveal ridges of creamy paint underneath

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

Fig.35

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, detail of the background showing scratches in the grey paint layer due to the wiping of wet paint with paper or a cloth

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

Modigliani manipulated the surface in a variety of ways to create texture and modulate colour: employing wet-into-wet and wet-on-dry techniques; thin washes; sponging; inscribing into or wiping wet paint with a rag or sponge; and scraping away dry paint. The sitter’s collar, for example, is textured by tamping or sponging black and bright green paint on top of the white layer (fig.32). Parts of the woman’s dark dress, the background around her left hip (fig.33) and the intersection of her right hand and basket also reveal the use of sponging or blotting. In the left-hand side of the background, the artist scraped through the thin, dry upper brown layer in order to reveal the light colour of the painting underneath (fig.34).53 Elsewhere, scratch-like patterns suggest that Modigliani used cloth or paper to partially wipe away wet paint, revealing the dried layer below (fig.35). In these and other areas, he embraced the texture and colour of the underlying paint and incorporated them into his final composition.

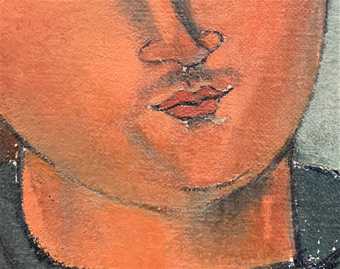

Fig.36

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, detail of the right jawline showing a deep blue linear brushstroke over the black outline. The olive-green lower layer is revealed in the gaps of pink, red and brown paint of the skin tones

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

Fig.37

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, detail of the lips and tip of the nose, showing deep red and black paint used in the outline and a dab of dark green paint that defines the v-shaped ridge of the upper lip

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

The Pretty Housewife appears to have been painted quickly, yet subtle details reveal the artist’s precise use of colour to enhance the vibrancy of the image. Modigliani used deep blue alongside dark brown and bone black to outline the face and the proper right eyebrow (fig.36).54 He delineated the apron with the same deep blue colour, which can be identified as synthetic (French) ultramarine.55 Modigliani blended green wet-into-wet to modulate the woman’s warm skin tones, especially at the outer edge of the face, and defined the v-shaped ridge of her upper lip with a single dash of dark green (fig.37). The pigment present in these details is predominantly viridian, but in one distinct dab at the edge of the sitter’s white collar, and possibly in thin applications along the left side of her face, the artist used emerald green.56 These cool green tones provide a vibrant complementary hue against the warm lead white and vermilion skin tones and the deep translucent red accents, likely alizarin lake, in the outlines of the nose and lips (see fig.37).

Fig.38

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, detail showing the lower olive-green layer exposed at the right edge of the proper left eye, and the black paint used to outline the grey paint of the eye

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

Fig.39

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, detail of the edge between the forehead and hair showing the exposed olive-green paint underneath

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

Fig.40

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, detail of the hair showing black lines in the tresses and layered ochre-coloured paint defining the locks of hair

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

Fig.41a

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, detail of the basket in normal light

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

Fig.41b

Amedeo Modigliani

The Pretty Housewife, closer detail of the basket in normal light showing diluted black lines and ochre-coloured diagonal brushstrokes that describe the weave

© 2023 Barnes Foundation

When he painted The Pretty Housewife, Modigliani did not completely ignore or conceal the earlier painting, but made use of the underlying colours. He painted the flesh tones of the face up to the edges of the facial features, leaving a border in reserve that allowed the underlying painting to become part of the present composition. Warm greens and greenish browns characterise the underlying palette in this region (figs.38 and 39). For the woman’s face, Modigliani utilised this mottled earthy undertone in a manner that echoes the flesh-tone layering techniques found in early Renaissance tempera paintings, with warm skin tones scumbled over cooler green hues.57 The hair is also built upon the underlying painting: the general outlines of the hair and ponytail are defined with black lines and yellow iron oxide brushstrokes on top of the underlying opaque earthy hues (fig.40). Modigliani treated the basket similarly to the hair: he delineated the weave with dilute black lines and painted the form with yellow iron oxide, allowing the dark colours beneath to create shadows (figs.41a–b).

The reddish-brown door that frames the sitter also contains subtle colour variations. Underlying greens and browns show through the thin, translucent final paint layer in the upper right quadrant. The brown colour itself is a complex mixture of pigments revealed by cross-section analysis: yellow, white, black and red pigment particles in a brown matrix provide a subtly modulated tone. The pigments identified include lead white (with a likely extender of barium sulphate), vermilion, iron oxides and bone black.58 Modigliani painted the bodice of the woman’s dress in a thin layer of bone black mixed with chromium-based green and/or yellow.59 Greens and blues in the earlier and final layers enliven what would otherwise be a drab grey apron; underlying reddish orange also filters through. Modigliani’s image does not extend all the way to the lower edge of the painting; the earlier painting is visible within this 6–18 mm gap, with streaks of brown, grey, light blue and a light minty green.60

It is unclear whether Modigliani executed the underlying paintings. As noted, the arch-type form that distinguishes the initial painted design is an unlikely form for the artist. The possibility that he applied some of the intermediary paint layers in an effort to conceal the underlying composition was also considered.61 However, the related gestural underdrawing and the broad, energetic strokes visualised in the MA-XRF maps are atypical for Modigliani, or indeed for any of his contemporaries. All of the artist’s extant early works depict human figures, and therefore the absence of anatomical features in the X-radiograph or in the elemental distribution maps of lead and zinc point to the underlying images being created by a different hand.62 Although all of the pigments identified in the second underlying painting are present in some of Modigliani’s paintings, this fact alone does not amount to a positive attribution.63 While it is tempting to continue deciphering the origin and meaning of the images underneath The Pretty Housewife, the endeavour may prove to be both futile and irrelevant. This painting demonstrates that Modigliani reused an old canvas and adapted it to his needs by incorporating or altering the forms and colours that were already on it, rather than completely obliterating them. He arrived at the final composition by utilising a seemingly random tapestry of underlying olive greens, earthy browns and yellows, pastel blue and green and even vibrant orange to enliven his subject and the space she inhabits. Modigliani also made use of the texture of the underlying paint, deliberately modifying the surface through scraping, wiping, blotting and scratching – reductive techniques that recall the artist’s beginnings as a sculptor.

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz 1916

Fig.42

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz 1916

Oil on canvas

813 x 543 mm

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

C161

Modigliani’s painting of Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago is a rare double portrait, commissioned by the Lithuanian-born sculptor Jacques Lipchitz on the occasion of his marriage to the Russian poet Berthe Kitrosser (fig.42).64 Modigliani and Lipchitz were close friends; both had Jewish backgrounds and had moved to France at a young age, and they frequented the same artistic circles in Paris. In his 1953 biography of Modigliani, Lipchitz recalls commissioning the portrait as a way of helping a friend who was struggling financially: ‘In 1916, having just signed a contract with Léonce Rosenberg, the dealer, I had a little money. I was also newly married, and my wife and I decided to ask Modigliani to make our portrait. “My price is ten francs a sitting and a little alcohol, you know,” he replied when I asked him to do it.’65

Lipchitz goes on to describe Modigliani’s working process for the portrait, which required two days of sittings. The first day was dedicated to sketching: ‘He made a lot of preliminary drawings,’ Lipchitz reported, ‘one right after the other, with tremendous speed and precision … finally a pose was decided upon – a pose inspired by our wedding photograph’. Although Lipchitz recalled up to twenty drawings, only nine related works on paper are known to exist.66 In these sketches Modigliani studied each sitter separately, varying the postures and framing. The drawings of Jacques show him both seated and standing, with his hands in multiple positions, while Berthe in all examples is seated, with her body turned to different angles and her face gazing forwards. The vertical lines near the centre of the background, likely framing a doorway or another architectural element, are consistently present in the sketches, occasionally with additional horizontal lines introduced to further define the indoor setting.67 Only one of the surviving drawings shows the couple together in a pose very close to the final painted image. The final pose is similar to the couple’s wedding photograph, although mirrored; in the photograph Jacques stands behind a seated Berthe with his hands on her shoulders.68

Fig.43

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, reverse

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago

The painting is on a medium weight unlined canvas attached to a five-member strainer with nails (fig.43).69 The canvas is a plain weave linen with an average thread count of 11.2 horizontal (warp) and 11.5 vertical (weft) threads per centimetre.70 The strainer, stamped with the number 25 on the lower member, is a standard size no.25 marine (basse) format (81 by 54 cm).71 Modigliani rotated the canvas to a vertical orientation for the portrait. As such, it is tall and narrow, tightly framing the couple.

Fig.44

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, detail of the drawn outlines defining Jacques’s facial features and chin

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago Conservation and Science Department

Fig.45

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, infrared photograph

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago Imaging Department

Fig.46

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, detail showing black dots along the edge of Jacques’s face

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago Conservation and Science Department

Modigliani painted the Lipchitz portrait on a thin lead white ground layer, which was probably applied to the canvas by the artist.72 The ground layer is confined to the image plane and covers an earlier painting on the canvas. The figures were outlined in black and blue paint directly on this ground layer, the placement and key features of each figure having been simplified and refined through the extensive series of preliminary drawings.73 The drawn outlines remain evident around the faces of the couple (fig.44). Many of these contours were strengthened with painted lines of black and blue during painting, obscuring the initial sketch in visible and infrared examination, leaving some question as to how extensive the initial sketch may have been (fig.45).74 A string of black painted dots visible along the left side of Jacques’s hairline may indicate Modigliani’s system for transferring the composition from a drawing on paper to the canvas (fig.46).75

Fig.47

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, detail of the rich blue paint used as a border between Berthe’s hair and face

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago Conservation and Science Department

Modigliani left the white ground visible between paint strokes, producing a luminous effect, particularly around Jacques’s facial features, which were thinly painted in comparison to those of the more densely painted Berthe. The palette used for the painting was limited. XRF analysis indicated the following pigments: lead white, vermilion, iron oxide or earth pigments, bone black and possibly Prussian blue.76 Modigliani painted within the confines of the initial sketched outlines as he filled in the figures and the background. There is limited mixing or layering of tones or overlap at the edges of the painted forms, apart from the black expanse that defines Berthe’s hair. A rich blue stroke of paint outlines the left side of her face and peeks out as an undertone, adding vibrancy and depth to the black form (fig.47).

Fig.48

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, detail of Berthe’s white collar

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago Conservation and Science Department

Jacques’s maroon suit is mostly a solid field of flat colour, apart from the three jacket buttons and two parallel horizontal black stripes just visible on each sleeve below the elbow. Similarly, Berthe’s dress has little sense of drape or fabric detail. Her lace collar is an off-white mass of dense paint with a few cursory strokes of white and yellow for texture, but little discernible detail or definition (fig.48).

Fig.49

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, detail of the loosely filled in and outlined polo neck

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago Conservation and Science Department

The background of the double portrait exhibits vigorous brushstrokes of blues and greys; a large patch of earthy yellow tones defines the otherwise unmodulated architectural space. The background was painted in after the figures, at which point Modigliani appears to have made slight adjustments to the positioning and angle of Jacques’s shoulders. The background slightly overlaps the top of his original shoulders to lower the torso and elongate the neck. Most of the artist’s attention appears to have been focused on the two faces, which contrast in tone and handling. Jacques’s face reads almost as a caricature. His jaunty expression is defined by dark eyes below arched eyebrows, an angled nose and small, puckered lips. Jacques’s left eye is a dense plane of blue-green and his right eye has a blue and black pupil surrounded by greyish white paint that provides subtle definition. His ears and hands are solid, flat planes of ruddy orange-red with no detail. His polo neck jumper embodies Modigliani’s quick painting technique: the form appears to have been outlined in black paint on white ground, filled in with a few expressive strokes of grey paint; the outline was strengthened and redefined with a stroke of black paint that does not quite follow the edges of the grey form (fig.49).

Fig.50

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, detail of the pressed and blotted paint surface

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago Conservation and Science Department

Jacques’s face is carefully contoured with orange and red, followed by a grey-blue tone used for shadows and definition. Modigliani manipulated the subtle balance of paint textures on the face by blotting or pressing the paint with paper, to impart a thin and blended appearance. The artist’s daughter Jeanne Modigliani described this technique, which has been observed in several paintings investigated for the current publication, recalling that her father occasionally ‘spread a sheet of paper over the fresh paint in order to obtain a better blending of his colours’ (fig.50).77

Fig.51

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, detail of the lively brushstrokes used to define Berthe’s nose

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago Conservation and Science Department

Berthe is more thickly painted than Jacques, lighter in tone and with a more expressive, open face. Her dark eyes are wide and she gazes directly at the viewer. Her face appears to have been painted from dark to light, with highlights of light yellow applied in thick, repetitive dabs to define her nose and the sides of her lips. Vertical brushstrokes of yellow define her chin, expand her face, and add texture to her forehead. Berthe’s nose and neck are the only areas of the painting that contain the dabbed strokes of impasto characteristic of Modigliani’s later works (fig.51).

Fig.52

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, detail of the orange brushstroke used to define the wrist of Jacques’s pocketed hand

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago Conservation and Science Department

Both figures lean slightly to the left, while the verticals in the background are tilted slightly to the right. With neither element parallel to the canvas edges, the painted space feels askew. This is further emphasised by the brown and black rectangle to the left of Jacques’s head. It is unclear if the form is a framed work of art or an architectural detail, but it adds to the picture’s odd sense of space and motion. Modigliani used brushwork and detail to create a sense of depth within the tightly cropped composition. Jacques’s proper left lapel is clearly defined, as are his extended proper left arm and sleeve, which helps to bring them forward in space. In contrast, his right lapel is barely visible, and the left side of his body is very loosely painted, with little indication of dimension or texture. The exposed wrist visible between Jacques’s pocket and sleeve was defined with a simple brushstroke of orange applied over the maroon suit (fig.52).

Fig.53a

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, detail showing the grey triangle above Berthe’s head, which appears to be an area of Jacques’s suit that was scraped away to the white ground before the grey was painted

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago Conservation and Science Department

Fig.53b

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, detail showing the grey triangle to the right of Berthe’s face that was added on top of painted forms to define her chin and the edge of Jacques’s arm

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago Conservation and Science Department

Fig.53c

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, detail showing the grey triangle that defines the opening of Jacques’s jacket, painted directly on top of the white ground

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago Conservation and Science Department

Modigliani used triangles of grey paint to separate forms, for example to delineate Jacques’s left arm and Berthe’s head in space. The artist scraped away a small area of Jacques’s suit above Berthe’s head before painting in a grey triangle to define the negative space between arm, head and torso. He added the grey triangle to the right of Berthe’s face on top of painted forms to define her chin and the edge of Jacques’s arm. In contrast, he painted the grey triangle that defines the opening of Jacques’s jacket early in the painting process, directly on top of the white ground (figs.53a–c).

According to Lipchitz, Modigliani declared the painting complete at the end of the first day of painting:

We looked at our double portrait which, in effect, was finished. But then I felt some scruples at having the painting at the modest price of ten francs; it had not occurred to me that he could do two portraits on one canvas in a single session. So I asked him if he could not continue to work a bit more on the canvas, inventing excuses for additional sittings. ‘You know,’ I said, ‘we sculptors like more substance.’ ‘Well,’ he answered, ‘if you want me to spoil it, I can continue.’78

Fig.54

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, detail of the the lower right portion of the background showing grey underpaint and drips that suggest the yellow was painted over an earlier grey layer

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago Conservation and Science Department

There is physical evidence that – in compliance with Lipchitz’s suggestion – Modigliani did continue to work on the painting. Drying cracks to the left of Berthe’s face suggest possible alterations were made in this area, perhaps to cover up a chair back or other background detail. Dark undertones below her neck suggest the artist made some alterations to the collar opening. To the right of Berthe’s head, below Jacques’s hand and sleeve, there are grey drips unrelated to the final image; these may hint at further adjustments or an area of grey background that Modigliani wiped away before painting in the arm and hand. A grey undertone to the yellow plane in the background also suggests that this portion of the background may not have originally been yellow (fig.54).

Closer examination of Berthe’s face reveals that the artist reworked and softened her features. Her nose was originally thinner, straighter and more angular, with a squared tip. Modigliani expanded the nostrils, particularly along the left edge. The eyes were originally thinner, angled and higher on the face. He broadened the proper left side of her face slightly, making the face more open and rounded, and slightly altered the angle of the head. In contrast, he did not alter Jacques’s features. As a result, the painting exists as a hybrid of painting techniques: Jacques retains the thin, graphic, angular quality more characteristic of Modigliani’s earlier portraits, while Berthe’s face is more thickly layered and worked, her softer features heralding a new, more naturalistic style for the artist.

Fig.55

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, detail of the inscription that was scratched into and then painted on the dried paint surface

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago Conservation and Science Department

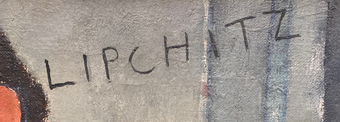

The painting is signed in the upper right in black paint. The name ‘LIPCHITZ’ appears between Jacques’s head and the signature. The name was scratched into a dry layer of paint with a sharp instrument before newly painted letters were overlaid. These were added at roughly the same spacing as their incised counterparts, if at slightly more of a slant. The incised lettering remains visible upon close examination, particularly the T and Z, below and to the left of the painted letters (fig.55).

Fig.56

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, X-radiograph

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago Conservation and Science Department

Fig.57

Amedeo Modigliani

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, detail showing green paint visible on the bottom tacking edge that is related to the underlying composition

Photo: Art Institute of Chicago Conservation and Science Department

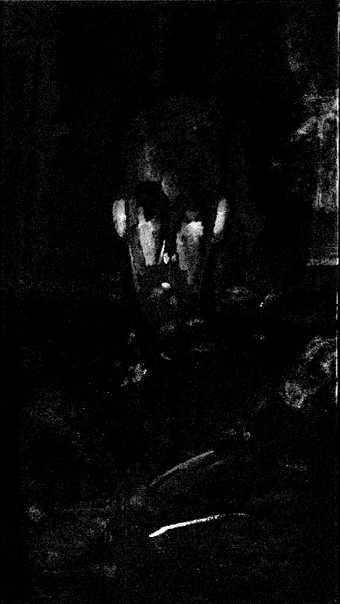

An X-radiograph of the painting reveals a figure beneath the portrait of Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz (fig.56).79 The figure is positioned at the upper right of the canvas, with a mass of centrally parted hair, or possibly a hat, crowning the head; the gender of the sitter cannot be determined.80 The figure’s face appears to have been laid in with an X-ray absorbing paint such as lead white, but the rest of the figure and surrounding composition are difficult to discern. A number of brushstrokes in X-ray absorbing paint hint at other features. Attempts to further identify underlying forms with transmitted IR images were unsuccessful.81 The early image is not readily visible on the surface; even viewed under raking light, the upper paint layers hide the underlying texture and palette. Evidence of the earlier composition’s palette is only apparent on the tacking edges, where there are remnants of green, brown and grey paint that do not correspond to the palette or appearance of the Lipchitz portrait (fig.57).

The underlying painting on the canvas could be a work by Modigliani. It bears some resemblance to Modigliani’s early portraits of women with large masses of hair, such as the aforementioned Bust of a Young Girl, Bust of Nude Woman with Hat (recto) and Maud Abrantes (verso), but it is more likely the work of another artist that Modigliani obtained for the purpose of painting over. The painted canvas appears to have been cut down to fit the present strainer. Indeed, Lipchitz mentioned that Modigliani ‘came with an old canvas – which he liked because it already had some preparation on it’.82

Chromium was detected in the green paint on the bottom tacking edge that is thought to be associated with the first composition. This suggests the presence of a chromium-based green pigment in the earlier painting that appears to be absent from the Lipchitz portrait.83 Otherwise, the XRF analysis was not able to differentiate between the pigments in the two works, nor was it able to rule out Modigliani as the author of the earlier composition.

An additional image is visible on the reverse of the Lipchitz canvas: the head of a woman in profile is outlined in a black dry medium, upside down, above a series of dark, wavy lines that may indicate lettering, perhaps a word (see fig.43). The drawing lies under the horizontal crossmember on the reverse of the strainer and thus must have been present on the canvas before the current stretching. It is possibly linked to the earlier composition on the canvas, but does not appear to be related to the Lipchitz commission. Modigliani seems to have boldly repurposed the older, abandoned canvas with little intent to hide its age or earlier use, even for this important and personal project.

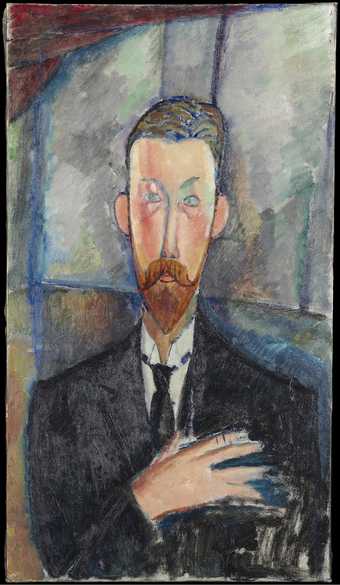

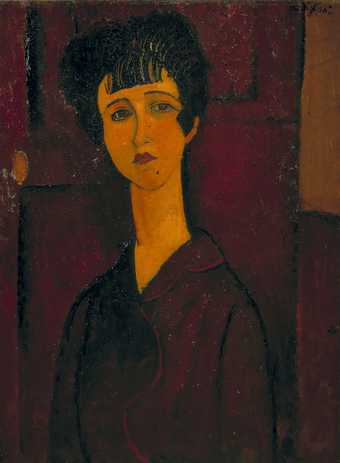

Portrait of a Girl c.1917

Fig.58

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Girl c.1917

Oil on canvas

806 x 597 mm

Tate

Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

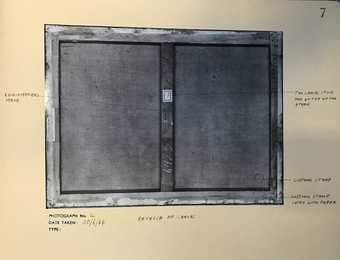

Portrait of a Girl c.1917 in the Tate collection (fig.58) was listed as ‘Portrait of a Young Woman, Mademoiselle Victoria’ in the catalogue of a 1929 exhibition at the Lefèvre Gallery, London, and as ‘Young Woman (Victoria)’ in both Ceroni’s and Joseph Lanthemann’s publications of 1970.84 It entered the Tate collection in 1933.85 The painting is signed but not dated, and there is some uncertainty as to when it was painted: Lanthemann dates the picture to 1916, while both Ceroni and Arthur Pfannstiel state it was painted the following year.86 Stylistically, the portrait can be placed towards the latter end of the period Modigliani spent in Paris between 1915 and 1917, during which he primarily produced portraits.87 Moïse Kisling, an artist and acquaintance of Modigliani, stated that the subject was an English girl and that the painting was a commission.88 It was, however, in the possession of the art dealer Léopold Zborowski in 1921, which suggests either that it was not bought by the sitter, or that Kisling was mistaken and it was in fact painted after a model; there are several examples of commissions by Modigliani being rejected by their sitters and changing hands during his lifetime.89

The painting was lined with a wax-resin adhesive at Tate and attached to a new stretcher in 1964.90 The trimmed and unpainted edges of the canvas extend around the back of the 1964 stretcher, probably indicating that the canvas retains its original dimensions. It measures 80.6 by 59.7 centimetres, which corresponds to a no.25 paysage canvas (81 by 60 centimetres) turned on its shorter edge.

Fig.59a

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Girl, photograph of the painting on its original strainer before conservation treatment in June 1964, as illustrated in the Tate conservation record

Tate Conservation file

Fig.59b

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Girl, detail showing the stamp on the crossmember

Tate Conservation file

The painting’s original strainer was photographed before treatment in 1964 (fig.59a). It was made of softwood with mortise and tenon joints and secured with four nails in each corner, like those used for both Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window and Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz. On the central crossmember was an artists’ supplier’s stamp which appears to read ‘PASCAL COCCOZ [?] / 12, Rue de Douai’ (fig.59b).91 This same mark appears on the portrait of Paul Alexandre in Front of a Window and Redheaded Woman in Evening Dress 1918 (Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia; C321). Modigliani is thought to have lived briefly in a mixed-use space at 62 Rue de Douai in around 1910, but it is not known whether he acquired canvases at this location.92

The coarse linen canvas has 12.7 horizontal (warp) and 11.4 vertical (weft) threads per centimetre and a very open weave.93 The warp-thread angle map shows strong cusping that extends into the painting from the top edge, while there is weak cusping apparent along the bottom edges and along both vertical edges.94 This indicates that the support was cut from a larger canvas that was already primed, with the painting’s top edge corresponding to an unprimed selvedge on the larger canvas. The canvas has a very thick glue size, which must have been applied cold, and which has helped to retain the texture of the weave. This layer includes some chalk, so it could be a thin chalk/glue priming rather than a thick size layer, as has been observed on the linen canvas for Madame Zborowska 1918 (Tate).95 The thin white commercial priming for Portrait of a Girl consists mainly of a single layer of lead white.

Fig.60

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Girl, ultraviolet image

Photo: Tate Photography

Fig.61a

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Girl, detail in visible light of the signature in the painting’s upper right corner

Photo: Tate Photography

Fig.61b

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Girl, photomicrograph of the signature in ultraviolet light

Photo: Joyce Townsend

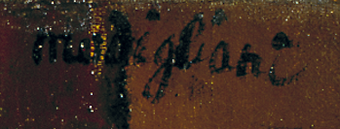

An image of the surface of Portrait of a Girl in UV light (fig.60) indicates a very hazy early varnish which may have been partially absorbed by the medium-rich red paint of the background; a second varnish, applied after the painting was framed (and hence not extending to the edges of the painting on any side); and a thick top layer of conservation varnish that extends over the whole picture.96 Examination in UV light also suggests that the signature ‘modigliani’ at the top right was applied in slightly thinned black or dark paint onto the already dried paint surface, beneath all the varnish layers (fig.61a–b).

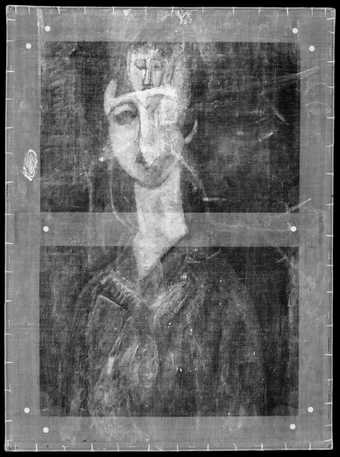

The varnishes have yellowed, and they confer a highly glossy and warm appearance on the already warm red and brown colours of the portrait, making the flesh tones appear rather orange. The lining of such an open-weave canvas may also have caused a degree of darkening. The earliest varnish has developed drying cracks along with the paint. Such drying cracks are unusual in Modigliani’s works and indicate that the upper layers of oil paint may have been painted over earlier applications that had dried some time before. This is the first indication that there is something under the surface.

Fig.62

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Girl, X-radiograph

Photo: Tate Photography

Fig.63

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of a Girl, transmitted light image

Photo: Tate Photography

Fig.64

Amedeo Modigliani

Woman Seated in Front of a Fireplace (Beatrice Hastings) 1915

Oil on canvas

805 x 645 mm

Private collection

C58

The X-radiograph of Portrait of a Girl (fig.62) reveals an earlier underlying image in the same orientation: a three-quarter length portrait of a woman, seated and slightly to the left of the centre of the canvas, her arms curved in front of her small-waisted body. Her elongated head is visible in the X-radiograph beneath the thickly painted and highly textured hair of Portrait of a Girl, which reaches almost to the top edge of the canvas. The transmitted light image (fig.63) suggests that the background is thinly painted in contrast to the figure, and raking light reveals little of this underlying image except for the curved arms. The woman bears a strong resemblance to the sitter in Woman Seated in Front of a Fireplace (Beatrice Hastings) 1915 (C58; fig.64), thought to be a portrait of the British writer, poet and journalist Beatrice Hastings, who was Modigliani’s partner from mid-1914 to mid-1916. Hastings was born in England, raised in South Africa and, having returned to England, relocated to Paris in 1914 to become a correspondent for The New Age: A Weekly Review of Politics, Literature and Art. Hastings had much in common with Modigliani: she was well read, well travelled, fiercely intellectual, artistic and a fellow foreigner in the bohemian avant-garde of Paris during the war.

There are several striking similarities between the underlying image in Portrait of a Girl and Woman Seated in Front of a Fireplace: both sitters wear their dark hair piled on top of their head, with a jagged fringe; both have oval-shaped faces with narrow pointed chins, have long necks and wear a dark long-sleeved dress with a high v-shaped neckline. The face in the X-radiograph is slimmer than that in the portrait of Hastings, but a secondary outline to the right of the face is discernible, which suggests Modigliani may have revised the contour in favour of a thinner face. The eyebrows, eyes and nose resemble those seen in other portraits of Hastings. The nose is reminiscent of the ‘cubist’ portraits that Modigliani painted in 1915, such as Madam Pompadour (Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago; C58) – a portrait of Hastings in which the nose is flattened with exaggerated triangular nostrils and the lips are bisected with vertical and horizontal lines. The thick application of paint in the upper part of Portrait of a Girl obscures the lips in the underlying painting, so it is not possible to compare the mouths.