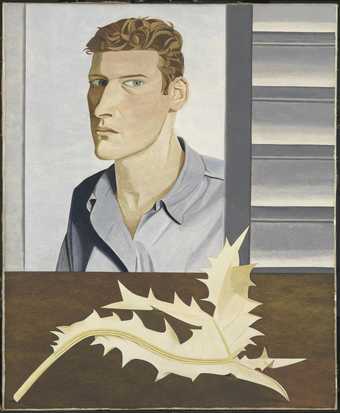

Lucian Freud

Two Plants

(1977–80)

Tate

Lucian Freud's Two Plants 1977–80 is today celebrated as being the impeccably obsessive rendition of an impossibly intricate vegetal composition that no other artist had previously dared to tackle. Densely clad, the felted foliage of Helichrysum petiolare (licorice plant) dominates the upper portion of the painting with a tight, rhythmic pattern. The elongated, bronze-green leaves of Aspidistra elatior (cast iron plant) mercilessly slit the lower part of the canvas. An intentionally unbalanced solution that foregrounds the anatomical characteristics of each species – the result is a true plant-triumph. It is a painting in which plants appear as bare as they possibly could – proudly engulfed in that laconic (and sometimes unnerving) essence that only apparently unremarkable plants embody.

And yet, it took time for Two Plants to be fully understood. Freud recalls that he went to Tate in 1980 when the work was first hung there to see how people reacted to it. To his dismay, he saw them ‘looking at the painting and going past it and then looking at the one after it as if there had been a sign saying “This Way to the Next Picture”’. He admitted that he had wanted the painting ‘to be quiet but not as quiet as all that’.

However, the ‘quietness’ of Two Plants is what lends the painting its originality. So, why might the work’s baroque boldness have failed to impress its first viewers? I think it had nothing to do with its quality, nor with the daring composition. But as a brave and radical departure from the tradition of Dutch Golden Age still-life painting, Two Plants is devoid of any classical symbolism. Since the 17th century, Western audiences had been educated to look at plants and flowers in paintings only to hear their symbolic voices. Daffodils – some of the earliest flowers to return every spring – spoke of rebirth and resurrection. Daisies told stories of innocence, beauty and love. Strawberry flowers professed the value of chastity. Still-life floral compositions constantly chattered, telling of our fears, dreams, emotions and values. In contrast, aspidistra and licorice plant – both strangers to sacred scriptures – have nothing to say. Two Plants, like Freud’s most accomplished paintings, is founded on the essentialist belief that the true voice of the subject can only be heard when symbolism is hushed.

It is not well known that Freud took three years to complete this work and that, all along, he grew these plants in his studio where they were regularly painted. As a result, Two Plants is not the impossibly perfect picture of plants at their aesthetic best – as a classical still life would have it – but the painterly record of a long-term negotiation of space, time and light that unfolded between painter and plant in the silence of the studio. In this sense, Two Plants is a groundbreaking attempt to align the silence of plants to the silence of painting: an opportunity to embrace the radical alterity of plants and engage in a silent dialogue in which our conception of vegetal beings and that of painting can grow together.

Two Plants was purchased in 1980 and is on loan to the exhibition Lucian Freud: Plant Portraits, Garden Museum, London, until 5 March.

Giovanni Aloi teaches art history, theory and criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and is Editor-in-Chief of Antennae: The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture. He is the author of Lucian Freud Herbarium and curator of Lucian Freud: Plant Portraits at the Garden Museum.